Philosophy in Color: The Jonang Lineage for the Wutai Shan Buddhist Garden 2025 Rangbala Thangka Exhibition

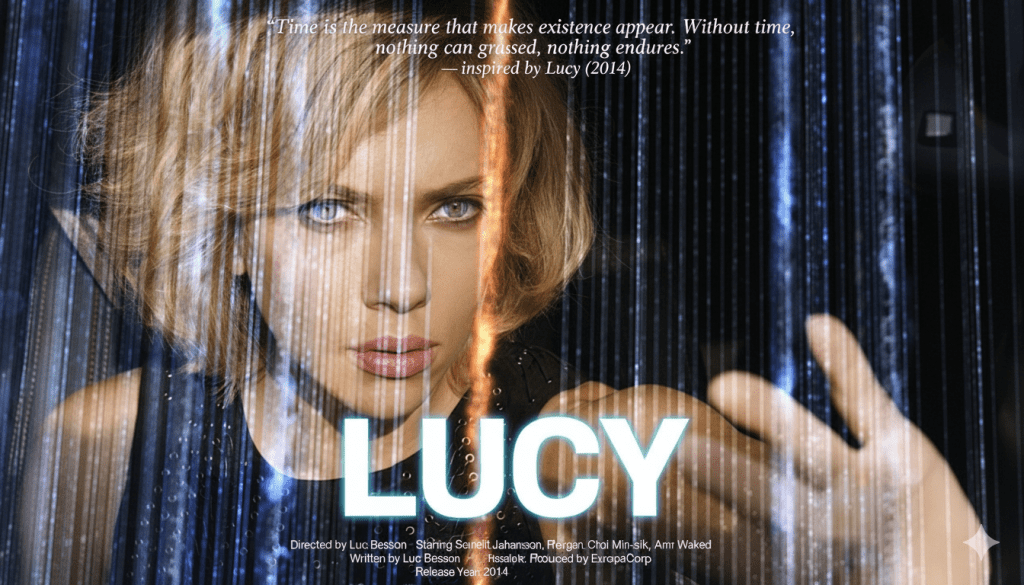

“Time is the measure that makes existence appear. Without time, nothing can be grasped, nothing endures.”

— inspired by Lucy (2014)

In Buddhism, time is not only the measure of existence but also the wheel that binds beings to the cycle of birth and death. The Jonang lineage, through its philosophy and its mastery of the Kālacakra, the Wheel of Time Tantra, offers a unique vision of how to transcend that wheel and uncover the timeless reality of Buddha-Nature.

「時間是讓存在顯現的度量。沒有時間,就無法觸及,無法持續。」

——靈感取自電影《露西》(2014)

在佛教中,時間不僅是存在的度量,也是將眾生束縛於生死輪迴的巨輪。覺囊傳承,憑藉其獨特的哲學觀和對時輪金剛法的完整傳承,展現了一條超越此輪、證得超越時間的佛性真實之道。

The Jonang (ཇོ་ནང་, Jo-nang) lineage is a distinct school of Tibetan Buddhism known for two features: its bold Shentong (gzhan stong) philosophy of emptiness, and its full preservation of the Kālacakra Tantra. While long suppressed by political forces, Jonang continues to challenge and enrich the Buddhist understanding of reality and liberation.

Rangtong and Shentong: Two Understandings of Emptiness

All Tibetan schools accept that phenomena are empty, but they disagree about what “emptiness” ultimately means.

Rangtong: Self-Empty

The Rangtong view, upheld by Gelug and widely in Nyingma, Sakya, and Kagyu, insists that everything—both relative appearances and ultimate truth—is empty of inherent existence (svabhāva). The highest wisdom is to realize that there is no essence anywhere: ultimate truth itself is described only by negation.

This is a radical deconstruction: nothing stands, nothing remains. Freedom is found in cutting through illusion until even the concept of ultimate reality dissolves into pure absence.

Shentong: Empty of Other

The Jonang Shentong interpretation does not deny this, but it adds another dimension. It agrees: all conditioned, impermanent things are empty of true existence. Yet it insists: the ultimate reality—the Buddha-Nature (tathāgatagarbha)—cannot be reduced to mere negation.

- It is “empty of other”: empty of illusion, but not empty of itself.

- It is the eternal, deathless ground, already endowed with the qualities of enlightenment.

- It is luminous, permanent, pure, and unchanging.

Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292–1361), Jonang’s greatest systematizer, described this reality in his masterwork Mountain Dharma. He called it the “Great Self,” the “Absolute Body of Buddha,” the “indestructible vajra.” These terms were not meant to affirm a worldly self, but to emphasize that beyond impermanence lies a positive ultimate—a ground of liberation that truly exists.

In Dolpopa’s vision, Rangtong clears away illusion, but Shentong reveals the radiant presence that remains when illusion is gone.

The Practice: Kālacakra Tantra and Six-Fold Vajrayoga

This philosophy is lived through the Kālacakra Tantra, preserved in its entirety by Jonang.

The crown jewel of this tradition is the Six-Fold Vajrayoga, a set of profound meditations on the subtle body and mind. These practices refine the winds and channels of consciousness until all conceptual obscurations collapse, and the innate luminous awareness shines forth.

Here, doctrine and practice meet: the Shentong view of Buddha-Nature as positive, eternal reality is directly experienced in meditation.

Suppression and Survival

- Foundations: The lineage began with Yumo Mikyö Dorje in the 12th century, a disciple of the Indian master Somanātha, and was firmly established by Dolpopa in the 14th century at Jonang Monastery.

- Suppression: In the 17th century, under the Fifth Dalai Lama, Jonang monasteries in Central Tibet were forcibly converted to the Gelug school. Shentong writings were restricted, and the lineage was politically erased from the “map” of Tibetan Buddhism.

- Survival: In the eastern regions of Kham and Amdo, Jonang masters preserved the lineage, focusing on retreat and transmission of Kālacakra practice. Though marginalized, the tradition continued uninterrupted.

Recognition and Resurgence

For centuries, textbooks spoke of “Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism” (Nyingma, Sakya, Kagyu, Gelug). Jonang was omitted—not because its philosophy lacked depth, but because of historical suppression.

This changed in 2011, when His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama formally recognized Jonang as an independent school. Since then, it has seen a quiet revival, with monasteries in Tibet and communities worldwide drawing renewed interest.

Why Jonang Matters

The Jonang lineage raises profound questions:

- Is ultimate truth merely the absence of illusion (Rangtong)?

- Or is it a presence beyond illusion (Shentong)?

- Is enlightenment described best by silence and negation, or by affirming the eternal qualities of Buddha-Nature?

For Jonang, both are needed. Rangtong clears away what is false. Shentong reveals what is true.

This gives Jonang a distinctive voice in Buddhism: a vision of emptiness not as a void, but as the deathless expanse of Buddha-Nature, radiant and indestructible. Its philosophy is matched by its practice, in the Wheel of Time meditations that lead directly to this realization.

Conclusion

The story of Jonang is one of resilience. Suppressed for centuries, it endured in remote mountains, carried by yogis and scholars who refused to let the lineage die. Today, it re-emerges, reminding us that emptiness is not simply the negation of all things, but also the uncovering of a luminous ground of awakening that has always been present.

Appendix: Rangtong vs. Shentong: Two Visions of Emptiness

The history of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy can be read as a great dialogue between two ways of understanding śūnyatā (emptiness). The Gelug school, founded by Tsongkhapa (1357–1419), became the most influential advocate of Rangtong (“self-empty”). The Jonang school, with Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292–1361) as its towering figure, became the champion of Shentong (“empty of other”).

Tsongkhapa’s Rangtong: Emptiness as Absolute Negation

For Tsongkhapa, the ultimate truth is the absence of inherent existence (svabhāva) in all things.

- All phenomena are empty — both relative (changing appearances) and ultimate (truth itself).

- To describe ultimate truth as having any inherent quality risks falling into eternalism, a subtle clinging to a “true essence.”

- Thus, even Buddha-Nature (tathāgatagarbha) is not something positive or self-existent — it is simply a way of pointing to the potential for awakening once emptiness is realized.

Tsongkhapa emphasized a razor-sharp logic of negation: freedom comes only when the mind completely sees through the illusion of essence, leaving no conceptual foothold whatsoever.

For him, ultimate reality is nothing but the absence of illusion.

Dolpopa’s Shentong: Emptiness as Radiant Presence

Dolpopa agreed with Tsongkhapa that conditioned phenomena are self-empty. But he refused to reduce the ultimate to mere negation.

- Relative reality: empty of inherent existence (Rangtong applies here).

- Ultimate reality: not empty of itself, but “empty of other.”

For Dolpopa, the Buddha-Nature is:

- truly existent (bden par yod pa)

- permanent (rtag pa)

- pure and luminous (dag pa, ’od gsal)

- endowed with all enlightened qualities (yon tan)

He called this the “Great Self” (bdag chen po), the “Absolute Body of Buddha” (dharmakāya), and the “indestructible vajra.” He deliberately used strong, affirmative terms to counter what he saw as the danger of Rangtong: sliding into nihilism.

For Dolpopa, emptiness is not just absence—it is the infinite presence of enlightenment itself.

Why the Conflict?

- For Tsongkhapa and Gelugpas:

Dolpopa’s language looked dangerously close to reasserting a Hindu-style ātman (Self). They feared Shentong smuggled essentialism into Buddhism, contradicting the radical insight of Nāgārjuna’s Madhyamaka. - For Dolpopa and Jonangpas:

Tsongkhapa’s strict negation risked nihilism, leaving nothing to stand as the ground of liberation. They argued that without affirming the reality of Buddha-Nature, ultimate truth dissolves into an empty hole, which cannot inspire practice or sustain the path.

Complementary or Contradictory?

Some later Tibetan teachers suggested that Rangtong and Shentong are not mutually exclusive but complementary:

- Rangtong deconstructs illusion, removing false projections.

- Shentong reveals the positive ground, the luminous awareness that remains when illusion is gone.

In this sense, Rangtong clears the sky; Shentong shows the sun that has always been shining.

Why It Still Matters

This debate is not merely scholastic. It speaks to how we understand liberation itself:

- Is enlightenment the realization of pure absence?

- Or is it the unveiling of an eternal presence?

The Jonang lineage stands for the latter, offering a vision of the ultimate as real, radiant, and indestructible—and through the Kālacakra practices, it provides the yogic means to directly realize it.

✨ In summary:

- Tsongkhapa (Rangtong): Emptiness = absence of inherent existence everywhere. Buddha-Nature = potential only, not a true essence.

- Dolpopa (Shentong): Emptiness = absence of illusion. Ultimate = truly existent Buddha-Nature, luminous and permanent.

Together, they mark the two poles of Tibetan Buddhist philosophy: the via negativa of radical emptiness, and the via positiva of luminous Buddha-Nature.

Leave a reply to Dennis A Yap Cancel reply