Why Independence Thrives, Why Neediness Suffers, and What Movies Quietly Teach Us

Contemporary cinema often celebrates romance as emotional intensity, dependency, and dramatic entanglement. Yet a closer look reveals a quieter truth: many modern films contrast two radically different relational ecologies.

We can call them orchid relationships and cactus relationships.

Among all recent films, Ghosted stands out as the clearest, most playful, and most life-affirming portrayal of a healthy cactus archetype.

1. Cactus vs. Orchid: Two Ways of Relating

An orchid relationship is emotionally high-maintenance:

- frequent reassurance,

- constant validation,

- fear of distance,

- identity intertwined with the partner.

It flourishes only under continuous attention.

A cactus relationship, by contrast, is rooted in emotional self-sufficiency:

- independence,

- resilience,

- tolerance for distance,

- clear boundaries.

Cactus relationships are often misunderstood as cold, but in reality they are low-drama, low-maintenance, and stable—especially when life becomes intense or unpredictable.

2. 🌵 Ghosted — The Modern Cactus (and Why It’s Fun)

Ghosted

This film is fun because it does something rare:

👉 it presents a cactus relationship without tragedy, bitterness, or emotional damage.

Ana de Armas’s character, Sadie, is the ultimate cactus:

- self-contained,

- emotionally independent,

- mission-oriented,

- playful rather than guarded,

- capable of affection without dependency.

Her strength is not emotional withdrawal, but emotional sovereignty.

Chris Evans’s character initially embodies a more orchid-like tendency—seeking closeness, reassurance, and emotional clarity. Yet instead of collapsing into dysfunction, the film allows him to grow toward cactus stability.

Why Ghosted works so well

- Independence is portrayed as attractive, not cold

- Romance exists without emotional burden

- Neither character needs to “fix” the other

- Love becomes an addition, not a necessity

Most importantly, Ghosted is fun.

It shows that cactus energy does not mean grim solitude — it can be light, humorous, flirtatious, and alive.

This is why Ghosted stands apart from darker cactus archetypes.

3. Why Purpose Changes Relationship Needs

For those pursuing an overarching purpose—a scientist, artist, code-breaker, or a bhikkhu—an orchid relationship can become a heavy burden and a serious obstruction.

A needy relationship:

- fragments attention,

- drains mental energy,

- amplifies fear of loss,

- and entangles identity with another person’s emotional weather.

This is why figures such as Nikola Tesla chose celibacy, and why bhikkhus undertake brahmacariya.

For a bhikkhu, this choice is not about rejecting intimacy out of aversion.

It is about streamlining the mind—removing emotional turbulence so attention can be fully directed toward a true and ultimate liberation and freedom from worldly entanglement.

4. Other Cactus Archetypes (Darker, Heavier)

Atomic Blonde — The Professional Cactus

Lorraine Broughton (Charlize Theron) is emotionally self-contained, guarded, and efficient. Any attachment is a liability. In high-risk environments, emotional neediness becomes a point of failure. The film quietly argues that survival favors the cactus.

The Prestige — Purpose Over Romance

Two magicians sacrifice relationships, morality, and even identity for mastery. Love becomes secondary—or instrumental. The film exposes the dark side of purpose: when the craft eclipses everything else, orchids cannot survive.

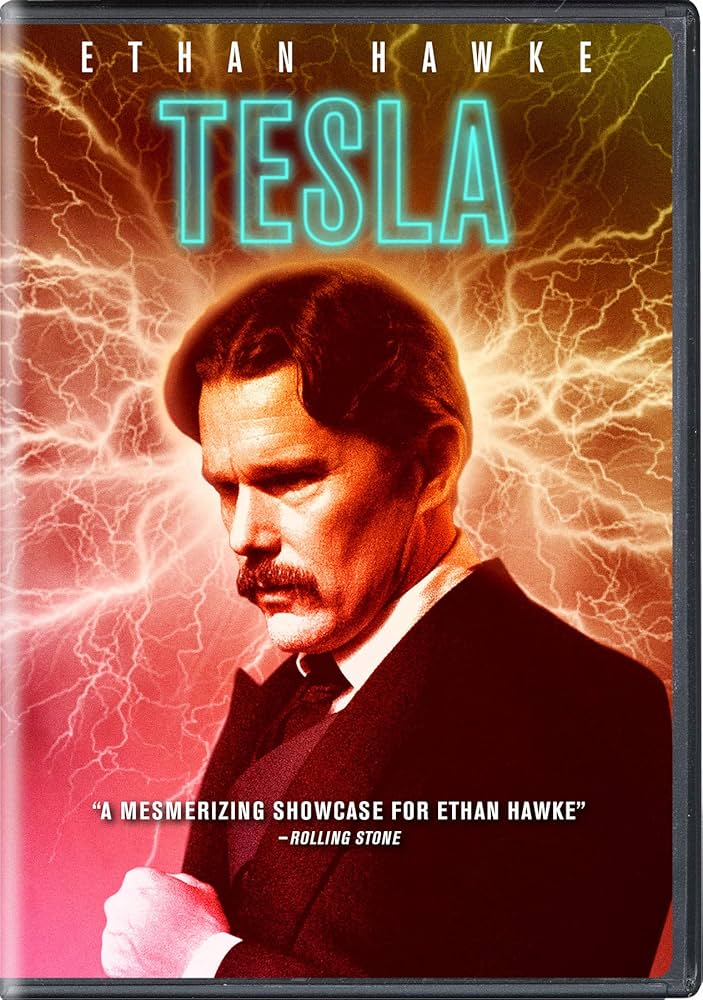

Tesla and The Imitation Game — The Solitude of Genius

Tesla believed sexual and romantic attachment diverted creative energy. Alan Turing is portrayed as emotionally prickly, misunderstood, and singularly focused. In both films, cactus-like solitude enables world-altering work—at great personal cost.

Good Will Hunting — Defensive Prickliness

Will’s emotional distance protects his inner world. The film explores the tension between genius and vulnerability: can a cactus learn to open without losing itself?

5. The Spiritual Threshold: From Orchid to Truth Seeker

Siddhartha — Leaving the Orchid Garden

Based on Hermann Hesse’s novel, this film explicitly shows the transition from sensory pleasure and attachment to the worldly life of a spiritual seeker. Romantic intimacy is not demonized—but ultimately relinquished as insufficient for awakening.

For a bhikkhu, this mirrors the move from relational dependence to inner independence—a prerequisite for deep concentration and clarity.

6. When Orchid Neediness Becomes Tragic

Blonde — The Orchid That Breaks

The film portrays the painful split between Norma Jeane and the “Marilyn” persona. Here, extreme emotional neediness meets public projection and exploitation. From a bhikkhu’s perspective, the tragedy lies in a mind turned entirely outward—seeking love, identity, and safety in the world.

Beauty and fame become chains, not blessings.

Deep Water — Toxic Attachment

This film depicts a destructive loop of craving and control. Extreme neediness and suppressed jealousy feed each other until collapse. It is a stark illustration of clinging—how identity fused with another person leads not to intimacy, but suffering and death.

(Note: This film, like Blonde, is dark and psychologically heavy; it is mentioned here for analysis, not recommendation.)

7. A Bhikkhu’s Perspective: Why Brahmacariya Exists

From Gautama’s Dhamma perspective, orchid relationships amplify:

- craving,

- fear of loss,

- identity fixation,

- and emotional reactivity.

These states obstruct stillness.

Brahmacariya is not anti-love.

It is pro-clarity.

By reducing relational neediness to near zero, the mind becomes:

- quiet,

- unified,

- resilient,

- and capable of deep concentration.

This inner stillness is the gateway to freedom—something no worldly relationship, however loving, can provide.

Conclusion: Not All Gardens Lead to Peace

Some lives flourish in gardens of mutual care.

Others require the austerity of the desert.

Cinema repeatedly shows this truth:

those who pursue a singular purpose—or liberation from worldly suffering itself—often become cacti, not orchids.

The question is not which is “better,”

but which path you are walking.

For those seeking spiritual awakening, emotional self-sufficiency is not coldness.

It is freedom from unnecessary suffering—and the space where clarity can finally grow.

Leave a comment