Epigraph

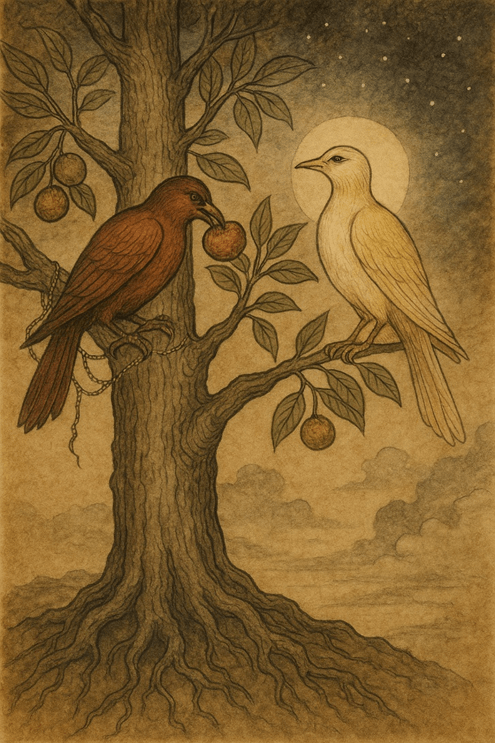

“Two birds, inseparable companions, dwell on the same tree.

One eats the fruit, sweet to taste; the other looks on, without eating.”

— Ṛg Veda 1.164.37; Muṇḍaka Upaniṣad 3.1.1

Part I — The Ache of Mortality

1. The Vast Night

The night stretches without end.

Stand beneath the stars, and you feel it. The sky is not a ceiling but an immeasurable expanse. Countless sparks scatter across the darkness, some flickering faintly, others burning bright. Some already dead, their light only now arriving.

In that silence, a human stands — fragile, a handful of breath and bone. A heart that beats fewer than three billion times in its span. A mind that remembers a little while, then forgets. A body destined to weaken, wrinkle, and return to dust.

And yet, standing under the night sky, something in us strains upward. Something whispers: I am more than this body. I am more than this passing moment.

This whisper has followed humanity for millennia. It is the spark that gave birth to poetry and song, to ritual and philosophy, to temples of stone and prayers carved into clay.

Pause here.

Have you ever felt it yourself? That ache when you looked up into the dark sky and knew, with a knowing deeper than thought, that your brief life cannot be the whole story?

2. The Ache of Mortality

Every human life is shadowed by impermanence. Children grow. Parents age. The strong fall. The beloved die. Empires rise in splendor, only to crumble. Even the stars themselves collapse — their corpses drifting as ash in the cosmic wind.

This ache is not a defect. It is the clearest sign of our humanity. To know that we will die is also to know that we long for more. To feel the wound of mortality is to feel the call to transcendence.

Ancient seers named this longing. The Veda called it the yearning of the soul to soar beyond birth and death. The Greeks gave it wings in myth, telling of Psyche ascending to the realm of the gods. The Daoists spoke of cultivating the inner elixir to live forever among the immortals. The Pharaohs built ladders of stone, carrying their kings to Orion.

All of these testify to the same truth: mankind does not rest content with death.

The ache of mortality is universal. It has driven seekers into deserts, forests, and mountains. It has inspired both austerities and innovations, both monasteries and laboratories. Behind every quest — for eternal youth, for genetic mastery, for digital immortality — is the same burning refusal: This cannot be the end.

3. The Archetype of the Two Birds

The Ṛg Veda gave a riddle to hold this truth: two birds, inseparable companions, dwell upon the same tree.

The tree is the body. And more than that, it is the cosmos itself, the great tree whose roots stretch into the abyss and whose branches touch the heavens.

One bird eats. This bird is restless, always seeking. It feeds upon the fruits of the tree, sometimes sweet, sometimes bitter, always fleeting. It eats because it must. Without eating, it cannot live.

The other bird does not eat. It only sees. Silent, luminous, unmoving. It belongs to another sky, beyond hunger, beyond death.

This image is not just ancient poetry. It is the map of our very being. Within each of us there is an eating bird — the ego, the garment of survival. And there is a watching bird — the eternal spark, the manussa essence, deathless and serene.

The ache of mortality is born from their tension. The eating bird consumes to survive, but knows it must one day fall. The watching bird remembers that it was never meant to die.

4. Why the False Self Must Feed

But why should the eternal bird share its tree with such a restless companion? Why should the deathless spark be trapped in a garment of flesh and fear?

The answer lies in the law of the cosmos. Naked, the spark cannot remain here. The universe is governed by dissolution; what arises must fall, what is born must die. To endure in such a place, the eternal spark requires an interface.

That interface is the false self — the eating bird, woven of three strands:

- Craving (rāga): the drive to grasp, to cling, to sustain.

- Aversion (dosa): the drive to resist, to protect, to defend.

- Ignorance (moha): the veil of forgetting — without which the spark would refuse to remain in such a world.

Thus the false bird is both protector and prison. It shields the spark, yet hides its origin. It allows survival, yet blinds us to eternity.

The ache of mortality is the true bird’s lament, muffled beneath the restless cries of its companion.

5. The Ache That Awakens

And yet, this ache is not despair. It is awakening. For in the very act of grieving death, we reveal that something in us is not willing to die.

This is why the ancients sang hymns, built pyramids, carved sutras, and sat in meditation. Not because they denied death, but because they knew death was not the end.

The Veda sang of two birds. The Upaniṣads declared that when the eating bird sees the watching bird, it is freed from sorrow. Gautama Buddha revealed how the eating bird can be stilled entirely, so the watching bird may take flight into the deathless.

The ache of mortality is thus not an obstacle to be overcome, but a summons to listen. It is the call of the watching bird, reminding us that we are not what eats, but what sees.

Reflection Pause

Close your eyes for a moment.

Imagine the tree of your life.

See the bird that eats — restless, hungry, always grasping, never satisfied.

See the bird that watches — silent, luminous, untouched, remembering the sky.

Ask yourself:

- Which bird am I feeding today?

- Which bird have I mistaken for myself?

- Which bird do I hear, softly calling me home?

Part II — The Archetype of the Two Birds

1. The Ancient Vision

The Ṛg Veda spoke in riddles, but its images carry a resonance that has never faded:

“Two birds, united companions, cling to the same tree.

One of them eats the sweet fruit; the other looks on without eating.” (Ṛg Veda 1.164.37)

The tree is the body, and beyond that, the entire cosmos. The eating bird represents the restless, survival-bound self, bound by craving, aversion, and ignorance. The watching bird represents the eternal spark — the true self, the manussa essence — luminous, untouched, deathless.

This dual vision was not confined to India. It appears across the world’s traditions in varied forms, each culture discovering in its own way that within man there are two lives: one that clings to the world, and one that longs for eternity.

2. Egypt — The Ka and the Ba

The Egyptians, perhaps more than any civilization, built their culture upon the question of death. For them, the human being was composed of multiple aspects, but two stand out: the Ka and the Ba.

- The Ka was the vital essence, tied to food, family, and offerings. It required nourishment even after death. Temples and tombs were stocked with provisions so the Ka would not wither. This is the bird that eats.

- The Ba was the free soul, depicted as a bird with a human face, able to leave the body and travel with the gods. It soared at night, returning by day, until it was finally united with the immortal stars. This is the bird that sees.

Pharaohs aligned their tombs with Orion, seeking to climb the “ladder of the sky.” The Pyramid Texts spoke of the king ascending as a falcon, his Ba joining the eternal constellations. The Egyptians knew: one aspect must feed, the other must fly.

3. Greece — Psyche and Logos

The Greeks carried a similar intuition. Psyche, the soul, was often imagined as a butterfly or a bird escaping the body at death. Yet they also knew another self — the Logos, the rational principle bound to the body and its desires.

Plato, in the Phaedrus, gave one of the most haunting images: the soul as a chariot drawn by two winged horses. One horse is noble, aspiring upward; the other is base, pulling downward. Only with discipline and vision can the charioteer ascend to glimpse the eternal Forms.

Here too we find the same archetype: one part that feeds on pleasure and pain, one part that longs to behold what never dies.

4. Christianity — Flesh and Spirit

Christianity inherited both the Hebraic longing for eternal life and the Greek imagery of ascent. The apostle Paul wrote of the battle between sarx (flesh) and pneuma (spirit).

- The flesh is like the eating bird — bound to sin, craving, corruption.

- The spirit is like the watching bird — awaiting redemption, destined to ascend to the heavenly kingdom of God.

Later mystics spoke of the scala paradisi — the ladder of ascent. John Climacus described the thirty rungs of spiritual struggle, culminating in love and divine union. The two birds reappear here as the Christian struggle: one bird eats the fruits of the world, the other waits for entry into heaven.

And yet, as you clarified for this book’s framework, the Christian God must be understood not as the cosmic Source but as a manussa ancestor — a being of the race of man, presiding over a heavenly kingdom. Thus, the Christian ascent is not dissolution but exalted companionship — to dwell forever in God’s heaven. Noble, honorable, but still within the ladder of becoming.

5. Daoism — The Immortal and the Mortal

The Daoists saw human life as a mixture of coarse and subtle forces. The hun (ethereal soul) aspired upward, while the po (corporeal soul) clung to earth.

Through refinement of breath, energy, and spirit — the alchemy of qi — Daoist adepts sought to transform themselves into xian, immortals who could ascend to the higher heavens. In the Daoist vision, the mortal bird feeds; the immortal bird cultivates, refines, and eventually flies free.

But here lies a crucial difference: for Daoists, the highest aspiration was dissolution into the cosmic Dao itself — the great Source. Noble in its way, yet as Gautama Buddha later discerned, such dissolution does not preserve the spark. It is annihilation, not eternity.

6. Why the Archetype Repeats

Why does the image of the two birds — or its equivalents — recur across civilizations?

Because every human being has felt the tension. Every culture has recognized that we live two lives at once:

- The temporal self, bound by necessity, craving, hunger, fear.

- The eternal self, luminous, yearning for what does not decay.

The Egyptians called it Ka and Ba. The Greeks called it Psyche and Logos. The Christians called it flesh and spirit. The Daoists called it hun and po. The Veda gave us the simplest, clearest image of all: two birds upon one tree.

7. The Buddha’s Turning of the Image

When Gautama Buddha appeared, he inherited this archetype. He too spoke of the restless bird — the self woven of craving, aversion, and ignorance. And he too spoke of the watching bird — the luminous citta, capable of release.

But his teaching added something radical:

- He refused to identify the watching bird with a permanent self.

- He refused to let the eating bird be polished into eternity.

- Instead, he revealed a path by which the eating bird is stilled, and the watching bird is freed — not into absorption, not into heaven, but into the unconditioned, Nibbāna-dhātu.

Thus, the archetype of the two birds became, in his hands, not just a symbol of longing but a map of liberation.

8. Reflection Pause

Close your eyes.

Picture the great tree of existence, its roots in darkness, its branches in the sky.

See the two birds:

- One flutters, restless, pecking, feeding, never satisfied.

- One is still, luminous, watching, remembering.

Ask yourself:

- Which bird have I followed most of my life?

- Which bird do I believe myself to be?

- What would it mean to let the eating bird rest, and to let the watching bird fly?

Part III — Why the False Self Exists

1. The Puzzle of Duality

If the true bird — luminous, eternal, deathless — is our essence, why should it need the company of a restless companion? Why should the manussa spark, pure and untouched, be forced to dwell in a body of clay and hunger?

This puzzle has echoed in every wisdom tradition. If eternity lives within us, why does it suffer? If light is our nature, why is it veiled? If we are sparks of the deathless, why must we struggle for food, fend off disease, and mourn our dead?

The ancients gave many answers. Some said it was punishment, a fall from heaven. Others said it was necessity, the will of gods. Still others saw it as a school — the soul’s training ground.

Gautama Buddha went further. He discerned that the false self is not random or accidental, but lawful. It is woven into the very fabric of the cosmos.

2. The Garment of Survival

The cosmos, as Gautama Buddha saw, is not a gentle garden but a law-bound system. Everything that arises must pass away. Stars collapse. Bodies decay. Worlds dissolve.

To endure within such a system, the manussa spark requires a garment — a protective interface that can operate by the cosmos’s rules. That garment is the false self, the eating bird.

It is stitched from three strands:

- Craving (rāga): The drive to seek, to grasp, to cling. Without craving, no being would eat, mate, or build shelter. Life would vanish in an instant.

- Aversion (dosa): The drive to resist what harms. Without aversion, no being would flee from fire, fight a predator, or defend a child. Survival would be impossible.

- Ignorance (moha): The veil of forgetfulness. Without it, the spark would recoil from this world, unable to tolerate decay and death. Forgetting its true home, it consents to stay — though at the price of delusion.

Thus, the false self is not a mistake. It is the condition of embodiment. It is the ticket price for existing within the cosmos.

3. The Double-Edged Sword

Yet what protects also imprisons.

- Craving sustains life, but also binds us in endless hunger.

- Aversion shields us, but also multiplies our hatred, violence, and fear.

- Ignorance spares us the shock of remembering eternity, but also blinds us to the exit.

The garment becomes a cage. What once was a shield becomes shackles. The eating bird, born of necessity, devours not only fruit but also freedom.

This is the double-edged sword of embodiment. Without the false self, the spark could not remain here. With the false self, the spark forgets its sky.

4. Cosmic Law and Debt

This necessity is not merely biological; it is cosmic. The universe itself requires sparks to wear garments of craving and fear. In so doing, the cosmos sustains its own order — birth, growth, death, dissolution.

In your larger framework, this is the cosmic tax: every spark that enters the cosmos must pay by wearing the garment of dissolution. It is the price of playing in this system.

The eating bird, then, is the collector of the tax. It ensures the spark participates in the endless turning of the wheel.

But Gautama Buddha saw further: while the tax is lawful, it is not final. There is a path of exit.

5. The False Self Across Cultures

Every civilization has intuited this necessity, though expressed differently:

- Egyptians: The Ka (vital self) needed constant offerings. Without it, the Ba (soul-bird) could not soar.

- Greeks: The base horse in Plato’s chariot was unruly but necessary; without it, the chariot could not move.

- Christians: The flesh (sarx) was corrupt yet unavoidable; without it, there could be no testing of faith.

- Daoists: The po (corporeal soul) tied the hun (ethereal soul) to earth, ensuring survival until refinement was complete.

In each case, the false bird is acknowledged as the unavoidable garment of mortality.

6. Gautama Buddha’s Radical Clarity

What makes Gautama Buddha unique is not that he recognized the false self, but that he declared it dispensable.

Where others sought to perfect it, purify it, or adorn it with virtue, Gautama Buddha taught: it must be abandoned. Not destroyed with violence, but starved of its fuel.

- Craving is ended not by indulgence, but by restraint.

- Aversion is ended not by conquest, but by compassion.

- Ignorance is ended not by speculation, but by direct seeing.

The eating bird cannot be trained to become the watching bird. It must fall silent. Only then can the true spark take flight.

7. Reflection Pause

Pause here.

Consider your own life.

- How much of your time is spent feeding the eating bird — chasing pleasure, avoiding pain, forgetting death?

- How often have you mistaken its voice for your own?

- Have you ever felt the quiet whisper of the watching bird — untouched, luminous, waiting?

The ache of mortality is not an accident. It is the sign that the garment no longer fits. It is the whisper that what once protected now imprisons.

8. Toward Release

The false self exists because survival here demands it. But survival is not liberation.

The Bodhisatta saw this with piercing clarity. The garment must be worn while one remains in the cosmos. But it must not be mistaken for the essence. And it must not be carried beyond its term.

The Buddha’s path is precisely this: to live within the cosmos without being consumed by it. To wear the garment lightly, while preparing for the moment when the watching bird will no longer need it.

At that moment, the garment falls, and the spark is free.

Part IV — The Watching Bird, The True Self

1. The Silent Companion

The Ṛg Veda described it simply: “The other bird looks on without eating.”

Silent. Still. Unmoving.

This is the true bird — the eternal witness, the manussa spark.

It does not hunger, because it belongs not to this tree. It does not decay, because it is woven from the deathless. It does not fight, because nothing can harm it. Even when trapped within the same tree as its restless companion, it remains untouched.

This is the mystery that has whispered across ages: within you there is something that has never been wounded, never aged, never died.

2. Beyond the Ego

Most of us confuse ourselves with the eating bird. We think: I am my cravings, my fears, my opinions, my body, my story. We build our identity around what we consume, resist, or imagine.

But the watching bird is beyond all this. It is not the ego, not the bundle of habits, not the flickering storyline we rehearse. It is the unconditioned presence — luminous, alert, silent.

When the Buddha spoke of anattā (non-self), he was not denying the existence of the watching bird. He was denying that the eating bird — the ego-self — is ultimate. To mistake the false bird for the true is the greatest delusion. To see beyond it is the beginning of liberation.

3. The Manussa Spark

In this book’s framework, the watching bird is more than a metaphor. It is the manussa spark — the eternal essence of the race of man.

- It is not native to the cosmos; it descended here.

- It is eternal only when preserved beyond the cosmos; here, it risks being consumed.

- It remains luminous and pure, even while trapped in the cycles of birth and death.

The spark remembers its true home, even when buried beneath layers of craving and ignorance. Its longing is the source of humanity’s dreams of immortality. Its ache is the engine of philosophy and mysticism.

Every vision of ascent — whether Vedic Ṛṣis, Egyptian Pharaohs, Greek philosophers, Daoist immortals, or Christian mystics — is ultimately the voice of the manussa spark, longing for release.

4. Never Defiled

A striking truth: the watching bird is never defiled.

No matter how deeply the eating bird gorges itself on bitterness or poison, the watching bird remains untouched. No matter how many lifetimes pass in ignorance, the spark does not rot. It may be obscured, buried, forgotten — but it is never stained.

This is why Gautama Buddha could say: “Luminous, monks, is this citta. It is defiled by adventitious defilements.” (Aṅguttara Nikāya 1.49-52).

Defilements cling to the garment, not the spark itself. The true bird, even when silent, remains radiant.

5. The Ache of Remembrance

And yet, though untouched, the watching bird suffers a different ache. It is not the ache of hunger, but the ache of longing. It remembers the sky.

When you feel, in your quietest moments, that life as it is cannot be all — that is the whisper of the watching bird.

When you sense, in beauty or silence, a glimpse of eternity — that is the spark remembering.

When you are dissatisfied even with great success or pleasure — that is the true bird reminding you that you are not made to feed, but to fly.

The ache of mortality is born from this remembrance. The eating bird fears death because it clings to fruit. The watching bird grieves because it knows it belongs to the deathless.

6. Across Traditions — The Eternal Witness

Every wisdom tradition has glimpsed this watching bird:

- Hinduism: The ātman, the eternal self, distinct from the body and mind. The Upaniṣads declared: “He who sees the other, radiant, becomes free from sorrow.” (Muṇḍaka 3.1.2).

- Christianity: The spirit (pneuma), groaning within, awaiting redemption. Paul spoke of an inner man renewed day by day, even as the outer man decays.

- Daoism: The hun soul, ethereal, rising upward after death, unbound by the decay of the po.

- Platonism: The soul that remembers the eternal Forms, recognizing beauty and truth as shadows of its true homeland.

Each tradition testifies that there is something within us untouched by decay, something that sees, remembers, and longs.

7. The Buddha’s Illumination

Where Gautama Buddha was unique is in how he treated this watching bird.

- He did not call it eternal self (ātman), because that would risk clinging.

- He did not merge it into a cosmic Source, because that would annihilate the spark.

- He revealed it as citta — luminous, purifiable, capable of liberation.

The task is not to define it, but to free it. Not to say, “This is who I am,” but to let it fly, beyond name and form, into Nibbāna-dhātu — the unconditioned, the deathless.

8. Reflection Pause

Close your eyes.

Imagine the tree of your body.

See the eating bird — restless, pecking, always hungry.

See the watching bird — luminous, silent, serene.

Ask yourself:

- Which voice do I usually follow?

- Can I sense the silent witness behind the noise?

- What would it mean to trust that luminous bird more than the restless one?

9. The Flight Beyond

The watching bird cannot be destroyed, but it can be forgotten. The eating bird cannot be perfected, but it can be stilled.

The Buddha’s path is to purify the citta, so the watching bird awakens fully. Then, unbound by craving and ignorance, it takes flight — not into another branch of the same tree, not into another cycle of heavens, but beyond the tree altogether.

The spark returns to its true sky.

The bird remembers its wings.

The eternal finds its freedom.

Part V — The Buddha’s Path of Release

1. From Symbol to Path

The Ṛg Veda gave the image of two birds. The Upaniṣads unfolded it into teaching. But it was Gautama Buddha who turned the image into a path — not poetry, not philosophy, but a practical training leading to the release of the watching bird.

The false bird cannot be polished into eternity. It cannot be argued away by clever words or ritual sacrifice. It must be stilled through a lived discipline — one that transforms the very conditions that keep it feeding.

This discipline has three strands, as precise and luminous as the three poisons are binding: sīla (ethical purification), samādhi (concentration), and paññā (wisdom).

2. Sīla — The Foundation of Purification

The eating bird thrives on turbulence. Lies, violence, greed, and sensual indulgence stir it into frenzy. If the watching bird is to awaken, the cage must be quieted.

This is the role of sīla, moral discipline.

- Refraining from killing, we soften aversion.

- Refraining from stealing, we weaken craving.

- Refraining from false speech, we purify the mind from distortion.

- Refraining from intoxicants, we preserve clarity.

Sīla is not morality for its own sake; it is the taming of the conditions that fuel the restless bird. A citta grounded in harmlessness becomes luminous, steady, and ready for deeper training.

3. Samādhi — The Flame of Stillness

Once the cage is quiet, the mind can be collected.

Through samādhi, the citta becomes steady, like a flame in windless air. The eating bird’s frenzy is calmed; the watching bird shines forth.

The jhānas refine awareness step by step:

- From rapture born of seclusion.

- To stillness beyond thought.

- To equanimity, radiant and clear.

- To the diamond flame of the fourth jhāna.

Beyond these, the arūpa samāpattis expand consciousness into infinite space, infinite consciousness, nothingness, and the subtlest perception.

Samādhi shows the vastness of the mind, and proves that the spark is not chained to the body. The bird can fly through heavens, touch suns and moons, hear the devas speak. But Gautama Buddha warned: even these sublime attainments end.

Samādhi is the great stabilizer, but not the final goal.

4. Paññā — The Sword of Seeing

The final strand is paññā, wisdom.

Wisdom sees what the eating bird conceals:

- That craving never satisfies.

- That aversion multiplies suffering.

- That ignorance blinds us to the deathless.

Paññā cuts through the delusion that the false bird is self. It sees directly the impermanence (anicca), unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), and non-self (anattā) of all conditions.

When this vision matures, the eating bird is not killed in hatred, but released in clarity. Its food is gone. Its motions cease.

And when the restless bird falls silent, the watching bird takes flight.

5. Nibbidā, Virāga, Vimutti

The Buddha described this process in three great stages:

- Nibbidā (Disenchantment): Seeing the endless feeding of the false bird as wearisome, unsatisfying, and futile.

- Virāga (Dispassion): The taste for feeding fades; craving loses its grip.

- Vimutti (Liberation): With nothing left to bind, the citta is released. The watching bird flies free.

This is not metaphor. It is a real transition. The unconditioned (asaṅkhata) — unborn, unbecome, unmade — is entered. The manussa spark steps through the Middle Exit, into Nibbāna-dhātu, the deathless beyond the universe.

6. The Release Is Not Annihilation

It is vital to understand: the release is not the destruction of the spark. It is not the dissolution of the bird into the Source, as Daoists and some Upaniṣadic thinkers imagined.

The spark is preserved. Its individuality is not clung to, but neither is it erased. It is carried into eternity, beyond the golden cage of the cosmos.

This is why Gautama Buddha’s discovery is unique. Others sought ascent, or dissolution. He found exit.

7. Reflection Pause

Close your eyes.

See the two birds upon the tree of your life.

- One is restless, feeding.

- One is silent, watching.

Now imagine:

- Sīla quieting the tree, so the feeding slows.

- Samādhi steadying the mind, so the restless flutter ceases.

- Paññā shining like a sword, cutting away delusion.

At last, the eating bird falls still.

The watching bird remembers its wings.

And the sky, boundless and deathless, opens before it.

8. The Path Is for You

The Buddha ended many discourses with a refrain: “If you can, become arahant — freed here and now. If not, become non-returner, purified enough to ascend to the Pure Abodes, where release will be completed.”

This is the direct invitation: do not settle for heaven, nor for dissolution. Purify the citta, gather your strength, and walk the path to the exit.

The path is not abstract. It is practical, lived, walked step by step. It begins with virtue. It matures in concentration. It flowers in wisdom. It ends in release.

This is the way the Buddha turned the archetype of the two birds into a roadmap for the human being.

Part VI — The Stars as Witness

1. The Ancient Sky

Long before scriptures were written, long before temples rose from stone, humanity’s first cathedral was the night sky.

The stars drew the eyes of shepherds and kings alike. They were countless, burning with mysterious fire, scattered across the blackness like jewels spilled from an unseen hand. Some shimmered faintly. Others flared with piercing light. Some wandered (the planets), others held their stations. All were silent, yet all spoke.

The night sky is humanity’s oldest scripture. To look upward was to glimpse eternity. To trace constellations was to imagine a greater order, to feel that life had meaning beyond the dust of earth.

2. Stars That Die, Stars That Endure

The ancients knew — though they could not have calculated — that stars are mortal. Some flare and fade, some vanish from the sky. Others seem eternal, fixed and steady, guiding travelers across deserts and oceans.

This dual vision mirrored the two birds.

- Some stars are like the eating bird: burning hot, consuming fuel, destined to die.

- Others are like the watching bird: steady, unchanging, enduring through ages.

The heavens thus became a mirror of the human soul. The restless and the eternal both shine in the sky.

3. Orion and the Pharaohs

The Egyptians aligned their pyramids with Orion’s belt, believing the king’s soul would ascend to the imperishable stars. To them, the stars were not mere lights but stations of immortality.

The Pyramid Texts spoke of ladders in the sky, upon which Pharaoh climbed like a falcon, his Ba joining the eternal constellations.

In this vision, the stars were witnesses — the gods themselves, or gateways to their realms. The soul that remembered its true nature would be welcomed among them.

4. The Greek Heavens

The Greeks too read the sky. They saw in its constellations the myths of gods and heroes — Orion the hunter, Perseus the rescuer, Andromeda the maiden, Zeus enthroned among thunderbolts.

For Plato, the stars were symbols of the eternal Forms. To gaze upon them was to recall what the soul had once seen before birth, when it traveled with the gods across the heavens.

Again, the sky became a witness to the soul’s double life: mortal body, immortal longing.

5. Buddhist Eyes on the Stars

Gautama Buddha also spoke of the stars, though differently. He did not worship them, nor map the soul’s destiny into constellations. Yet he used them as similes:

- Just as stars appear countless, so too are the worlds across the cosmos.

- Just as a shooting star flashes, so too does human life pass quickly.

- Just as the moon shines steadily, so too does the purified citta glow with peace.

He turned the heavens into lessons — not places to cling to, but reminders of impermanence. Even the brightest stars will fade. Even the loftiest heavens will end.

The stars are witnesses not only of eternity, but of the law of arising and passing.

6. The Cosmic Mirror

To stand beneath the night sky is to stand before a mirror.

- The eating bird is mirrored in stars that burn out.

- The watching bird is mirrored in stars that shine steady.

- The ache of mortality is mirrored in the collapse of galaxies.

- The promise of eternity is mirrored in the constellations that outlast empires.

The sky does not lie. It shows us what we are: both perishable and imperishable. Both restless and luminous. Both trapped and free.

7. The Stars as Teachers

Every culture took lessons from the stars.

- Navigation: They guided ships across the seas, just as the watching bird guides the soul through life’s ocean.

- Agriculture: Their rising and setting marked seasons, just as the restless bird marks time with hunger and change.

- Myth: Their stories explained why we ache for more, just as the Buddha’s teaching explained why we must not settle for less than freedom.

The stars are silent, but they speak. They tell us: Do not waste your life feeding only the restless bird. Remember the one who watches. Remember the sky that is your home.

8. Reflection Pause

Go outside tonight.

Look upward.

See the stars — countless, burning, some dying, some enduring.

Ask yourself:

- Which star am I following — the one that burns out, or the one that endures?

- Do I see in the heavens a reminder of my own double nature?

- Can I read the stars not only as decoration, but as scripture — a testimony to both mortality and eternity?

9. From Sky to Exit

For the ancients, the stars were often the final goal — to ascend and dwell among them forever. But Gautama Buddha taught something greater: even stars fade. Even constellations collapse. Even universes dissolve.

The true destiny is not to remain in the sky, but to pass beyond it. The stars are witnesses, not the destination. They remind us of the dual life, but they cannot themselves grant liberation.

The exit lies beyond them — in the unconditioned, the deathless, Nibbāna-dhātu.

Part VII — Reflection for the Reader

1. The Two Birds Within You

The Ṛg Veda spoke in riddles, but the riddle is not abstract — it is your life.

Two birds dwell within you.

- One eats. It is restless, driven by craving, aversion, and forgetfulness. It builds identities, chases pleasures, flees fears. It consumes the fruits of life, sweet and bitter, until the day it falls.

- One watches. It is silent, luminous, untouched. It does not eat, because it belongs not to the cycle of hunger and decay. It abides, remembering another sky.

Both are companions, inseparable while you live. But they are not equals. One is temporary, one eternal. One binds, one frees.

The question is not whether both birds exist — they do. The question is: which one will you follow?

2. The Ache You Already Know

You have felt it.

Perhaps standing under the stars, sensing that your life is more than dust.

Perhaps in grief, when someone you love was torn from you.

Perhaps in beauty, when music or silence pierced you with a longing you could not explain.

That ache is the whisper of the watching bird. It is not despair but memory — the memory that you were not made to die.

Every culture has given this ache a form: the Ka and Ba of Egypt, the psyche of Greece, the spirit of Christianity, the hun and po of Daoism. But beneath all these symbols lies the same truth: humanity carries within itself both mortality and eternity.

3. The Buddha’s Gift

Gautama Buddha inherited this archetype, but he gave it a new destiny.

He taught that the eating bird cannot be perfected. It must be released.

He taught that the watching bird is not to be merged into the Source, where it would be extinguished, but to be freed into the unconditioned — Nibbāna-dhātu, the deathless beyond the cosmos.

He gave us a path — sīla, samādhi, paññā — discipline, stillness, wisdom. A path not of ornamenting the cage, but of stepping beyond it.

And he gave us a promise: the Middle Exit is real. There is a gate beyond the heavens. It is narrow, hidden, but open. Whoever purifies their citta can walk through.

4. Standing Before the Gate

Imagine yourself now.

The tree of your life stretches upward, its branches heavy with fruit. The restless bird pecks and feeds. The luminous bird sits in silence.

Above the tree, the sky opens. Stars burn, galaxies swirl, worlds arise and collapse. The ache of mortality is written in their fire.

And then — you see it. A faint doorway of light, beyond the stars. The Middle Exit. The gate beyond becoming.

No one can carry you through. Not teachers, not scriptures, not even Gautama Buddha himself. He shows the way, but your feet must walk it.

The watching bird is ready. The question is whether you will silence the restless bird, whether you will trust the path that leads not upward, but beyond.

5. A Meditation

Close your eyes now, and let the reflection become practice.

- Breathe in, and see the eating bird — restless, feeding.

- Breathe out, and see the watching bird — luminous, still.

Breathe in, and feel the ache of mortality — the fear of loss, the hunger that never ends.

Breathe out, and feel the serenity of eternity — the spark that cannot be harmed.

Now imagine the gate beyond the stars, radiant, narrow, silent.

Say softly in your heart: I will not settle for heaven. I will not dissolve into the Source. I will walk the path beyond, into the deathless.

6. The Invitation

This is the invitation of this book, and of this blog.

- Do not polish the cage.

- Do not cling to the restless bird.

- Do not mistake heaven for eternity.

- Do not mistake dissolution for freedom.

Instead, purify your citta. Gather strength. Deepen stillness. Awaken wisdom.

The path is open. The map is clear. The gate stands waiting.

7. Closing Reflection

The Veda gave us the two birds.

The Upaniṣads taught that freedom comes when the eating bird sees the watching bird.

Gautama Buddha went further: freedom is when the eating bird falls still, and the watching bird takes flight beyond the cosmos, into Nibbāna-dhātu, the deathless.

Tonight, when you see the stars, remember: they are witnesses. They remind you of your dual life. They remind you that one part will pass, and one part will endure. They remind you that beyond their light lies a greater light, unconditioned, undying.

The rest is up to you.

Leave a comment