For centuries, Christianity and Buddhism have been seen as separate worlds — one centered on faith, the other on meditation.

But what if their roots run deeper than we think?

This groundbreaking essay uncovers the forgotten story of a shared healing lineage:

- Aśoka’s missions that carried the Dhamma beyond India to the Hellenistic world.

- The Therapeutae of Alexandria, contemplative “physicians of the soul” whose life mirrored the Theravāda Saṅgha.

- The Essenes of Qumran and John the Baptist, carrying the discipline back to Judea and preparing the way.

- The Desert Fathers and Mothers, who turned the Egyptian wilderness into the cradle of Christian monasticism.

More than history, this is a spiritual recovery project:

- It reveals Christianity not only as a faith but as a path of inner transformation.

- It invites readers to see salvation not merely as pardon but as healing of the soul.

- It calls East and West to meet again — at the source of the deathless, where the purified mind stands free.

“They show that the path of disenchantment, dispassion, purification, and liberation is not limited to one culture but is open to all humanity.”

This is an invitation to step back into the universal stream of wisdom — the same stream that flows from the Buddha’s Saṅgha to the monasteries of Christ, from Lake Mareotis to the deserts of Egypt, from the groves of India to the hearts of modern seekers.

Table of Content

1. Introduction — A Shared Longing

- Open with the universal cry: humanity’s longing to escape suffering and death.

- Frame Christianity and Buddhism not as rivals, but as siblings in the same great quest.

- Pose the central question: Could the Buddha’s path have influenced Christianity’s beginnings?

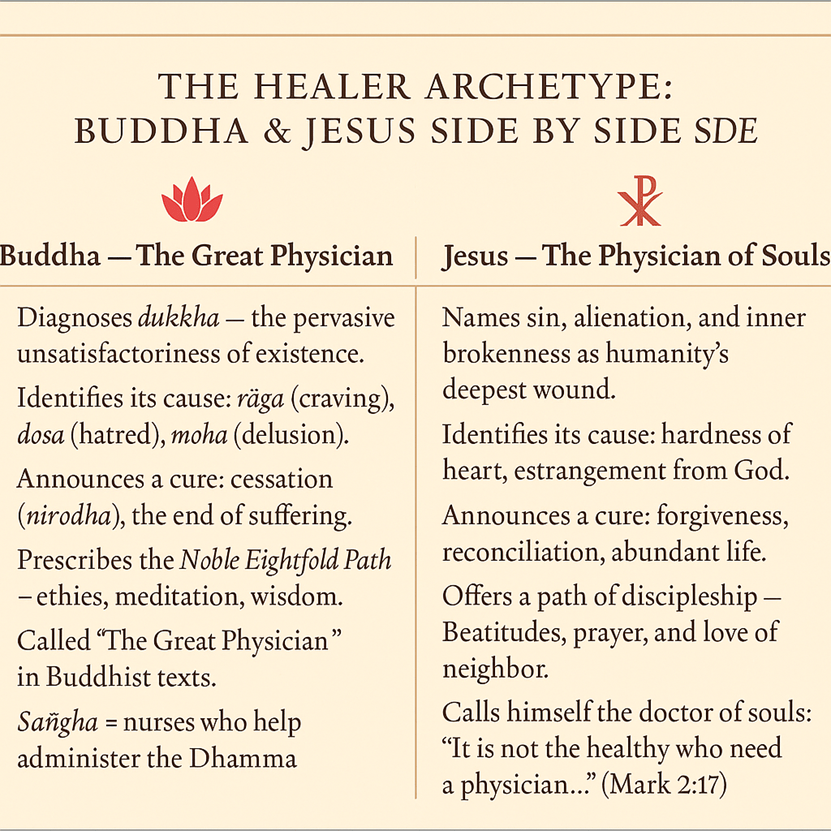

2. The Healer Archetype

- Buddha as the Great Physician, curing the disease of rāga (craving), dosa (hatred), moha (delusion).

- The word Therapeutae = “healers” — echo of thera-putta (“sons of the elders”) of Theravāda Buddhism.

- Therapy/therapist in the West still carries this linguistic inheritance.

- Connect with Jesus: “It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick” (Mark 2:17).

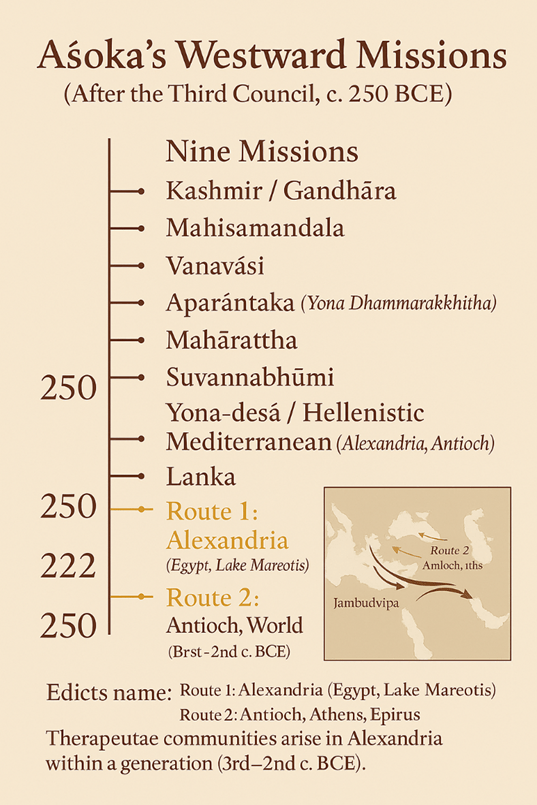

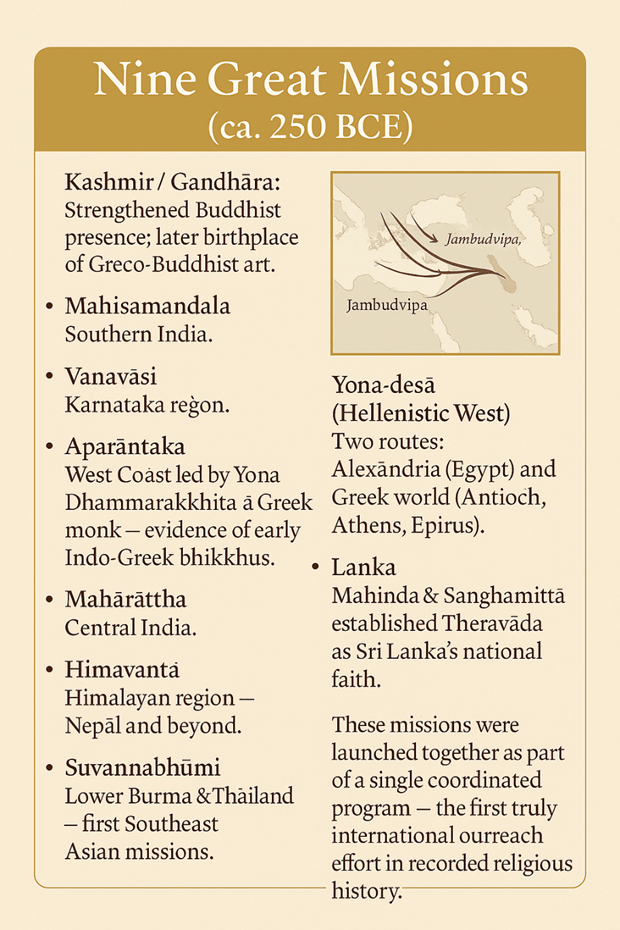

3. Aśoka’s Missions: The Dharma Goes West

- After the Third Council, Emperor Aśoka sends missionaries across the known world.

- Evidence of Indian emissaries reaching the Hellenistic Mediterranean.

- Seeds of renunciation and contemplative life planted in Alexandria.

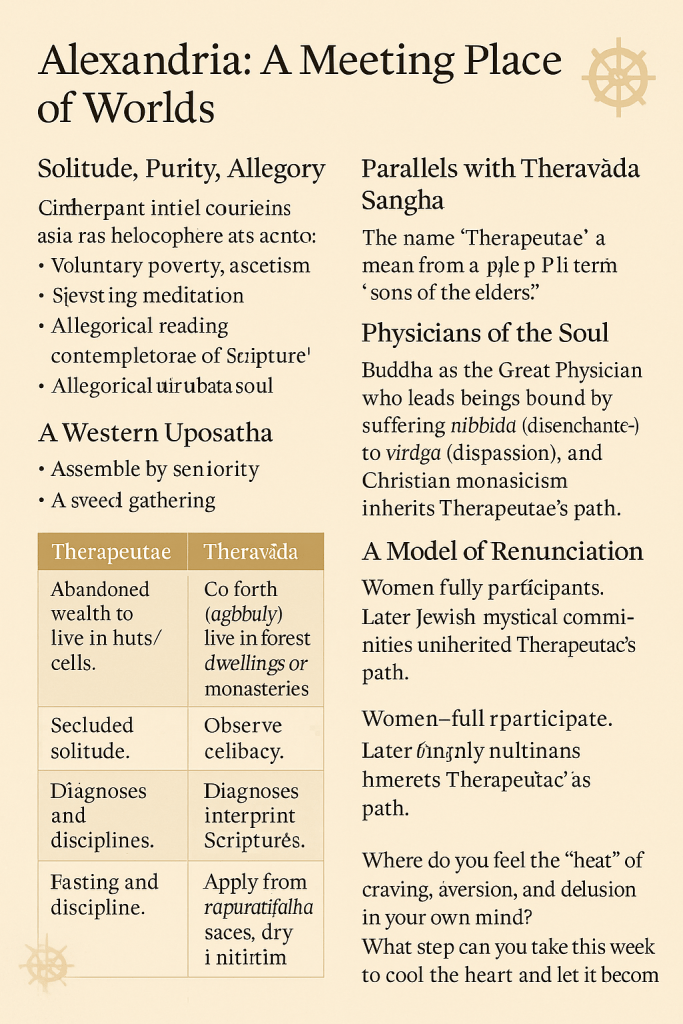

4. The Therapeutae of Alexandria

- Philo’s description of the Therapeutae: renunciation, meditation, hymns, allegorical interpretation of sacred texts.

- Striking parallels with Buddhist bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs.

- Likely fusion of Jewish mysticism and Theravāda monastic practice.

5. From Therapeutae to Essenes

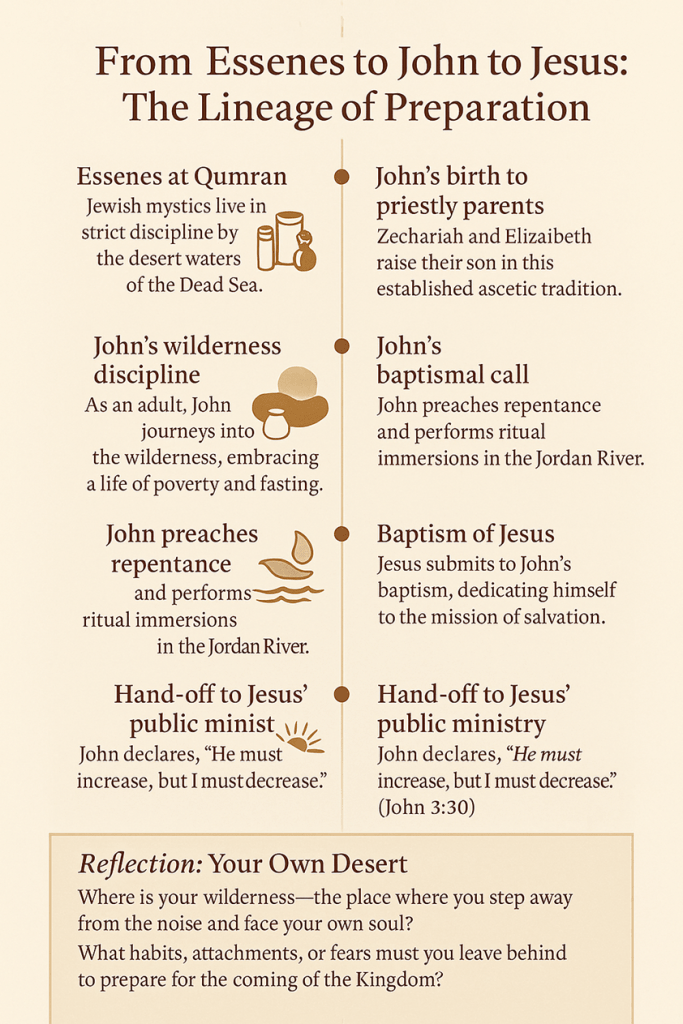

- Jewish mystics carried this discipline back to Judea.

- Essenes at Qumran: communal life, celibacy, ritual purity, apocalyptic expectation.

- Dead Sea Scrolls as witness of this spiritual discipline.

6. John the Baptist and the Preparation of the Way

- Parents Zechariah and Elizabeth: senior figures within this Essene stream.

- John’s desert life, fasting, ritual immersions = Essene discipline.

- John as the bridge between Essene–Therapeutae spirituality and Jesus’ mission.

7. Gnosis and the Early Christians

- Early Gnostics carried forward the contemplative and therapeutic dimension.

- Salvation not as legal pardon but as inner enlightenment.

- Parallels with Buddhist vipassanā — direct seeing of reality.

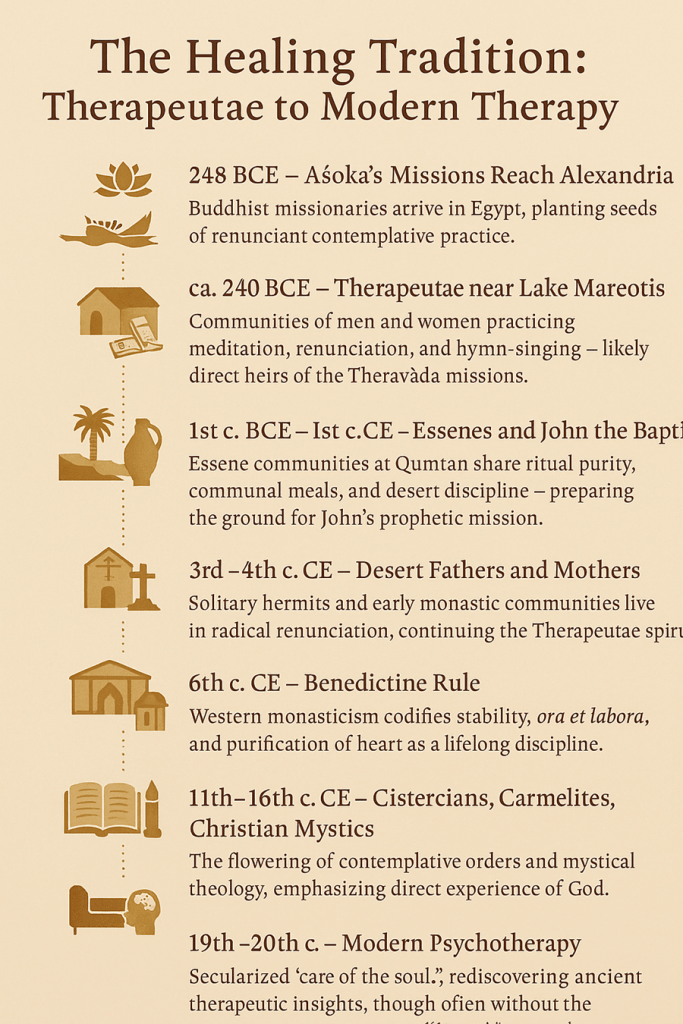

8. The Legacy: Monasticism and Modern Therapy

- Desert Fathers and Mothers continue the Therapeutae model.

- Christian monastic orders (Benedictines, Carmelites) inherit Buddhist-style renunciation and contemplation.

- Even modern psychotherapy owes its name — and its core function of healing the mind — to this lineage.

9. Conclusion — A Shared Healing Stream

- Christianity and Buddhism are not isolated; they are siblings in the great quest for deliverance.

- The archetype of the Returning One — Messiah, Christos, Metteyya — arises again and again to re-open the Gate.

- Invitation to Christian readers: rediscover your tradition not as separate from the East but as part of a universal therapeutic path to the deathless.

✨ Call-to-Action:

Encourage readers to reflect: What if the cry for deliverance that moved Buddha and Christ is the same cry in your own heart today?

1. Introduction — A Shared Longing

From Buddha to the Desert Fathers: The Forgotten Healing Lineage of Christianity

1.1 The Universal Cry of the Human Soul

Wherever humans have risen from the dust, gazed up at the stars, and wondered at the mystery of their own existence, one cry has gone up — sometimes in prayer, sometimes in protest, sometimes in silent longing:

Deliver us.

This cry is as old as humanity itself.

It is not the cry of one tribe or one religion, but the cry of the soul whenever it dares to face reality honestly:

- The cry of a Hebrew psalmist in exile, sitting by the rivers of Babylon, singing:

“Out of the depths I cry to you, O Lord; Lord, hear my voice.” (Psalm 130:1) - The cry of a Vedic sage chanting at dawn:

“mṛtyor mā amṛtaṃ gamaya — From death, lead me to the deathless.” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 1.3.28) - The cry of young Siddhattha Gotama, sitting under the rose-apple tree, seeing worms eaten by birds, and realizing:

“All beings must grow old, grow sick, and die — is there no way beyond?” - The cry of the Greek philosopher who longs to ascend from the cave of shadows into the light of eternal Forms.

- The cry of a modern man or woman who lies awake in the middle of the night, staring at the ceiling, and wondering whether the frantic cycle of work, pleasure, and disappointment could possibly be all there is.

Beneath every prayer for prosperity, every hymn for victory, every protest for justice, there lies this deeper cry:

Deliver us from impermanence. Deliver us from death. Deliver us from this endless cycle that turns joy into dust.

Far from being an expression of despair, this cry is the first sound of awakening.

It is the moment when the heart can no longer be content with half-measures — when no amount of distraction, pleasure, or philosophy can drown out the ache.

It is, in Buddhist language, the arising of saṃvega — the holy discontent that breaks the trance of saṃsāra and turns the soul toward liberation.

1.2 The Question That Haunts History

All of humanity’s great civilizations have been built on one question:

Is there a way out of death?

Some answer with resignation: Death is final, so eat, drink, and be merry — for tomorrow we die.

Some answer with bargaining: Sacrifice to the gods, obey the law, and hope for a place among the ancestors.

Some answer with transcendence: Purify the mind, walk the path, and step beyond death entirely.

It is this third answer that concerns us here.

It is the answer of the Buddha under the Bodhi tree, of the prophets who saw visions of resurrection, of the Christ who proclaimed: “I am the resurrection and the life.”

This book is not about religion as tribal identity or theological debate.

It is about the quest for liberation — the quest to cross the ocean of birth and death, to find the Gate that leads to the deathless.

1.3 Christianity and Buddhism: Not Rivals but Siblings

For many modern people, East and West are framed as opposites:

Christianity versus Buddhism, faith versus meditation, salvation by grace versus salvation by insight.

But what if this is a false dichotomy?

What if these two great traditions are not rivals but siblings — branches of the same great tree of humanity’s search for deliverance?

- Both see the world as impermanent, fleeting, unable to satisfy the deepest hunger of the soul.

- Both speak of a path — a way of transformation leading beyond mere survival.

- Both center their hope in a guide figure — a Buddha, a Messiah, an Anointed One — who shows the way and opens the Gate.

- Both insist that liberation is not merely intellectual assent but a change of life, a purification of mind and heart.

When viewed this way, Buddhism and Christianity no longer compete for exclusive truth.

They stand side by side as witnesses that there is something beyond death — and that it can be reached.

1.4 Could the Buddha’s Path Have Influenced Christianity’s Beginnings?

This question is not just an academic curiosity.

It is a doorway question — one that invites Christians to rediscover their own tradition with fresh eyes.

What if the spiritual technology of the Buddha — the discipline of renunciation, the healing of the mind, the practice of meditation — did not remain locked in India but traveled westward?

What if Jewish mystics in Alexandria encountered Buddhist missionaries sent by Emperor Aśoka, and formed contemplative communities known as the Therapeutae — “healers of the soul”?

What if some of these mystics returned to Judea and became the Essenes, the desert sect whose writings are preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls, whose way of life prepared the ground for John the Baptist — and through him, for Jesus?

And what if early Christianity, through these currents, inherited not only the prophetic fire of Israel but also the contemplative discipline of the East — so that Christian monasticism became, in some measure, the West’s continuation of the Buddha’s saṅgha?

If even part of this is true, it means that Christianity’s roots are deeper and wider than most of us have been taught.

It means that the meeting of Buddha and Christ is not a modern interfaith experiment but a long-forgotten historical reality — one that still carries power to heal the division between East and West.

1.5 Why This Story Matters Now

We live in a time of cultural exhaustion.

Many in the West are leaving the churches, yet still hunger for meaning.

Many in the East are rediscovering their own traditions, yet yearn for global dialogue.

In such a time, recovering this shared spiritual lineage is not merely an exercise in historical curiosity — it is an act of healing:

- Healing the false opposition between faith and practice, religion and psychology.

- Healing the rift between Eastern wisdom and Western spirituality.

- Healing the human heart by showing that we are not abandoned — that in every age, guides have arisen, gates have been opened, and the path has been renewed.

1.6 The Invitation to the Reader

This article is not written to prove a point but to invite a journey.

If you are a Christian, it may invite you to rediscover your own faith as a path of transformation, not merely belief.

If you are a Buddhist, it may remind you that the Buddha’s compassion extended beyond India — that the wheel he set in motion may have rolled farther than we think.

If you are a seeker, it may reassure you that your longing for liberation is not strange — it is the most universal of all longings, shared by prophets, sages, and mystics in every land.

Together, we will explore:

- How the cry for deliverance has echoed across civilizations.

- How Emperor Aśoka’s missions may have carried the Dhamma westward.

- How the Therapeutae of Alexandria bridged Jewish mysticism and Buddhist discipline.

- How the Essenes prepared the way for John the Baptist — and through him, for Jesus.

- How Christian monasticism may have inherited the Buddha’s healing technologies of the soul.

This is not an argument for syncretism but a recognition of a shared human story:

the story of the soul’s longing to return to the deathless,

and of the guides who appear, age after age, to show the way.

2. The Healer Archetype

“The Buddha is the Great Physician — the Dhamma is the medicine, and the Saṅgha are the nurses.”

(Milindapañha)

If the universal cry is humanity’s lament, then the answer must be more than a doctrine.

It must be a medicine — a way to actually heal what is broken.

Across traditions, the guides who answer this cry are not merely prophets, philosophers, or lawgivers.

They are physicians of the soul, healers of humanity’s deepest wound.

2.1 Buddha: The Great Physician

In the early Pāli texts, the Buddha is not portrayed as a distant deity but as a doctor — a compassionate healer who has diagnosed the human condition and found the cure.

The Four Noble Truths themselves are structured as a medical formula:

- Diagnosis: Dukkha — life as we know it is marked by suffering, impermanence, and unsatisfactoriness.

- Etiology (Cause): Samudaya — the cause of this suffering is not fate but a disease in the mind: craving (rāga), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha).

- Prognosis: Nirodha — the good news that this disease is curable; the fever can be brought to an end.

- Prescription: Magga — the Eightfold Path, the medicine to be taken until the cure is complete.

This is why in the Milindapañha, Nāgasena explicitly compares the Buddha to a physician, the Dhamma to the medicine, and the Saṅgha to the nurses who assist the patient in recovery.

“The Blessed One is like a skilled physician;

The Dhamma is like medicine that cures;

The Saṅgha is like the nurses who care for the sick;

And we who practice are the patients.”

In this sense, the Buddha’s entire mission was therapeutic — aimed at the healing of the mind.

He did not merely explain suffering; he treated it, root and branch, until the mind was free of its three great poisons.

2.2 The Disease of the Mind

Buddhism is uncompromisingly clear: our problem is not merely external injustice or physical pain.

The true bondage lies in the defilements of the citta — the heart-mind.

- Rāga (Craving): the fever of endless desire, always reaching for what is not yet attained.

- Dosa (Hatred): the fire of aversion and ill-will that burns both self and other.

- Moha (Delusion): the fog that blinds the mind, making us mistake what is impermanent for permanent, what is not-self for self, what is unsatisfactory for happiness.

These three are the real disease.

Even if we built a perfect society, if these poisons remain, suffering would still be generated.

Thus the Buddha prescribes not merely social reform but radical inner transformation — a medicine that reaches the root.

2.3 The Therapeutic Path

The medicine the Buddha gives is not a single pill but a whole discipline — a course of treatment that reshapes the entire being.

- Sīla (Ethics): the first phase of treatment — cleansing the bloodstream of gross impurities so that healing can begin.

- Samādhi (Concentration): the stabilization of the mind, calming the fever of restlessness so that deeper surgery can take place.

- Paññā (Wisdom): the final operation — cutting out delusion by directly seeing the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and non-self nature of all conditioned things.

When this process is complete, the patient is cured.

The Buddha calls this state arahatta — the mind utterly freed, the fires extinguished, the disease ended.

This is why Nibbāna is called amata — “the deathless” — not as a metaphor but as the final state where the conditions that generate death no longer arise.

“Religion is not a courtroom but a hospital — a place where the wound of existence is healed.”

2.4 The Name Therapeutae: Healers of the Soul

When we turn to the Therapeutae of Alexandria, we find that their very name points to this same archetype.

Philo, who describes them in detail, explains that Therapeutae means “healers.”

But they are not physicians of the body — they are healers of the psyche.

Their life is devoted to freeing the soul from passion, ignorance, and disorder.

They live in huts or cells, spend their days in study and meditation, gather on holy days to sing hymns and share insight.

If the word is indeed related to the Pāli thera-putta — “sons of the elders,” a term that would have been familiar to Aśokan emissaries — then these communities may have literally seen themselves as spiritual descendants of the Elders of the Buddha’s Saṅgha.

2.5 Therapy: The Lingering Echo

Even our modern word therapy is a descendant of this same idea.

It comes from the Greek therapeuein — “to attend, to serve, to heal.”

In the ancient world, the therapeutes was not merely a medical attendant but a servant of the gods, one who cared for the soul as well as the body.

Thus when we speak of psychotherapy today, we are still, however faintly, echoing this lineage:

the work of attending to the soul’s wounds, of healing the mind so that it can be whole.

Modern secular therapy, though stripped of its spiritual frame, still carries the DNA of this older healing tradition — a tradition that runs from the Buddha’s Four Noble Truths through the Therapeutae of Alexandria to the Desert Fathers of early Christianity.

“It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick. I have come to call not the righteous but sinners.” (Mark 2:17)

2.6 Jesus: The Physician of Souls

This healing archetype reaches one of its most powerful expressions in the person of Jesus.

In the Gospels, Jesus does not merely preach — he heals.

He touches lepers, opens blind eyes, restores paralytics, and drives out demons.

But these physical healings are signs of something deeper.

Jesus himself says:

“It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick.

I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners.” (Mark 2:17)

Here Jesus identifies himself not just as a prophet but as a physician — one who has come to heal the inner disease of sin, alienation, and despair.

The Greek word used here (iatros) is the same word for a medical doctor.

The Gospel writers deliberately present Jesus as one who cures humanity’s deepest sickness — not merely forgiving sin legally but restoring wholeness.

This is why early Christians called him Soter — “Savior,” which also means “Healer.”

In the ancient world, salvation and healing were not separate ideas — to be “saved” was to be “made whole.”

2.7 The Archetype Across Traditions

When we place the Buddha and Jesus side by side, the resonance is striking:

| Buddha | Jesus |

| Diagnoses the disease of dukkha | Names sin and brokenness |

| Identifies its cause: craving, hatred, delusion | Identifies its cause: hardness of heart, estrangement from God |

| Offers a path of healing (Eightfold Path) | Offers a path of healing (discipleship, Beatitudes, forgiveness) |

| Called the “Great Physician” in texts | Called the “Physician of souls” in the Gospels |

| His Saṅgha administers the medicine | His disciples are sent to heal and teach |

Both figures stand as archetypal healers, not simply preachers of doctrines.

Both seek to cure the disease of the human heart so that it can awaken to life beyond death.

2.8 The Healer as Returning One

Seen within the larger cosmic story, the archetype of the healer is also the archetype of the Returning One:

- The one who descends into the world’s sickness.

- The one who bears the suffering of others.

- The one who discovers or reveals the cure and offers it freely.

This is why in both traditions, the figure of the healer is celebrated not just as a teacher but as a savior:

one who does for others what they cannot do for themselves.

In Buddhism, the bodhisattva postpones final nirvāṇa to remain in the world as a healer of beings.

In Christianity, Christ descends into death itself to open the way for all.

2.9 Healing as the True Goal of Religion

This perspective reframes what religion is meant to be:

not merely a system of beliefs, rituals, or moral codes, but a hospital for the soul — a place where the wound of existence is treated until it is healed.

This is what the Therapeutae understood, living near Lake Mareotis: that the task of life is not to accumulate but to purify, not to conquer but to be cured.

Their very name became a prophecy: that the way of the Elders, the way of the Buddha, would one day bear fruit in the West as a tradition of soul-healing that would eventually blossom into Christian monasticism.

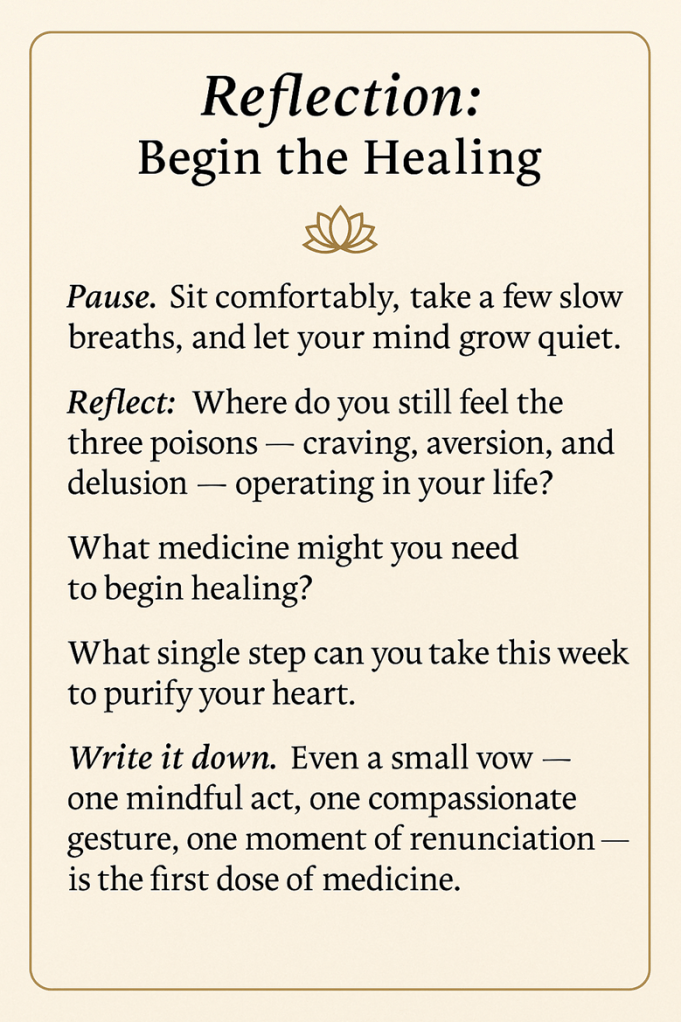

2.10 A Challenge to Modern Readers

To recover the healer archetype is to rediscover what is missing in much of modern spirituality:

- Faith without healing becomes mere belief — an intellectual assent that leaves the wound unclosed.

- Meditation without healing becomes mere technique — a way to relax but not to be transformed.

- Social reform without healing becomes mere activism — fighting symptoms without treating the cause.

The call of both Buddha and Christ is to go to the root — to submit to the medicine, however bitter, until the disease is gone.

2.11 The Invitation

As you read these words, pause and ask yourself:

- What are the poisons that still bind me?

- Where does craving, aversion, and delusion still twist my heart?

- Am I willing to receive the medicine — even if it means renunciation, discipline, transformation?

This is the beginning of healing.

This is the point where the cry for deliverance becomes a willingness to be cured.

2.12 Preparing for the Next Step

In the next section, we will follow this healing current outward — beyond India — into the wider world.

We will see how Emperor Aśoka, moved by compassion, sent emissaries to share the Buddha’s medicine with distant lands — and how one of those missions may have planted a seed in Alexandria that would flower into the Therapeutae, the Essenes, and ultimately the contemplative stream within Christianity itself.

3. Aśoka’s Missions: The Dharma Goes West

If the Buddha was the Great Physician, then Emperor Aśoka was his greatest pharmacist — the one who distributed the medicine to the widest possible audience.

Aśoka’s story is not merely one of royal patronage but of a civilizational turning point, when the wheel of the Dhamma was rolled out across continents, crossing linguistic, cultural, and political borders — and perhaps seeding the ground for spiritual revolutions far beyond India.

3.1 The Turning of Aśoka’s Heart

Aśoka (r. ca. 268–232 BCE), third ruler of the Maurya dynasty, began as a conqueror known as Chandāśoka (“Aśoka the Fierce”). He expanded his empire through relentless military campaigns until he reached Kalinga, a prosperous coastal state.

The resulting war was catastrophic. Ancient records speak of 100,000 dead and 150,000 deported.

Aśoka was shaken to his core.

In his 13th Rock Edict, he confesses:

“On conquering the Kalingas, a hundred and fifty thousand people were deported, a hundred thousand were killed and many times that number perished… His Majesty feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas.”

This remorse became the seed of transformation. Aśoka embraced the Buddha’s teaching and vowed to rule by Dhamma-vijaya — “conquest by Dharma,” replacing war with persuasion, and violence with compassion.

3.2 The Third Council: Consolidating the Dhamma

About a decade later (ca. 250 BCE), Aśoka convened the Third Buddhist Council at Pāṭaliputra under the arahant Moggaliputta Tissa.

Its goals were threefold:

- Purify the Saṅgha — removing corrupt or heretical members.

- Reaffirm the Tipiṭaka — the canonical teachings of the Theravāda lineage.

- Prepare a global mission — to carry the Dhamma far beyond India’s borders.

This council became the launchpad for the most organized spiritual outreach of the ancient world.

3.3 The Nine Great Missions

Immediately after the council, Aśoka dispatched nine missions simultaneously, a sweeping project that sent bhikkhus to the edges of the known world. The Mahāvaṃsa lists:

- Kashmir / Gandhāra

- Mahisamandala

- Vanavāsi

- Aparāntaka (led by Yona Dhammarakkhita, a Greek monk — evidence of early Indo-Greek Buddhists)

- Mahārāṭṭha

- Himavanta (Himalayan region)

- Suvaṇṇabhūmi (Lower Burma, Thailand)

- Yona-desā / Hellenistic Mediterranean — Alexandria, Antioch, Epirus, Macedon

- Lanka — Mahinda and Saṅghamittā, establishing Theravāda in Sri Lanka

This was no casual diffusion but a coordinated and universal vision of Dhamma as a gift for all nations.

3.4 The Western Routes: Two Pathways to the Mediterranean

The Yona mission was divided into two western routes:

- Route 1: Alexandria (Egypt) — reaching the intellectual heart of the Hellenistic world, a cosmopolitan city with a massive Jewish community and the Great Library.

- Route 2: Greek World (Antioch, Athens, Epirus) — entering the Seleucid and Macedonian spheres where philosophy, rhetoric, and mystery religions thrived.

This was a bold experiment — the Dhamma crossing the cultural frontier to meet Greek philosophy, Jewish mysticism, and Egyptian religiosity head-on.

3.5 The Yonas: India Meets the Hellenistic World

The Yonas (from Ionia) were Greek-speaking peoples who had settled in Bactria and northwestern India after Alexander’s conquests. By Aśoka’s time, they were part of the Mauryan cultural sphere.

In his 13th Rock Edict, Aśoka names five Hellenistic kings to whom he sent emissaries:

- Antiochus II (Seleucid Empire)

- Ptolemy II Philadelphus (Egypt)

- Antigonus Gonatas (Macedonia)

- Magas (Cyrene, North Africa)

- Alexander II (Epirus, Greece)

This is extraordinary — a Mauryan emperor communicating directly with Mediterranean rulers more than two centuries before Christ.

And Aśoka does not boast of conquest. Instead, he describes ethical and humanitarian reforms: tree planting, wells dug, hospitals built, animal slaughter forbidden, compassion encouraged. He prays that these kings too will embrace this moral revolution.

3.6 Archaeological and Textual Evidence

Modern evidence supports this east–west contact:

- Bilingual inscriptions (Greek + Aramaic) from Kandahar prove the Dhamma was proclaimed in Hellenistic languages.

- Gandhāran art fuses Greek realism with Buddhist themes — the first anthropomorphic images of the Buddha show him in a toga-like robe, with a halo.

- Greek writers such as Strabo and Plutarch mention “Indian philosophers” (gymnosophists) visiting the courts of Hellenistic kings.

This was not a one-time diplomatic exchange but a sustained cultural cross-pollination.

3.7 Alexandria: The First Western Saṅgha

Alexandria, with its Great Library and multi-ethnic population, became the natural landing point for the Theravāda missionaries.

Within a generation (late 3rd–early 2nd c. BCE), we see the emergence of Therapeutae communities near Lake Mareotis.

Philo of Alexandria describes them in detail:

- Renouncing property and living in simplicity

- Practicing chastity and meditation

- Spending days in solitude, nights in hymn-singing

- Gathering weekly for communal teachings and shared meals

Their very name, Therapeutae, likely echoes thera-putta — “sons of the elders.”

They were, in effect, a Western branch of the Theravāda Saṅgha, preserving the Buddha’s therapeutic path in Egyptian soil.

3.8 Transmission of the Lifestyle

Even where doctrinal transmission was partial, the monastic lifestyle spread:

- Renunciation and communal life

- Celibacy and purity codes

- Meditation-like prayer and chanting

- Fasting and ethical discipline

This lifestyle later appeared among the Essenes of Qumran, the Desert Fathers, and Christian monastic orders — all echoes of this transplanted Saṅgha.

3.9 Cross-Pollination of Ideas

Contact with the Hellenistic world was likely mutually transformative:

- Greek Logos philosophy resonates with the Buddhist Dhamma as cosmic law.

- Greek logic sharpened Indian Abhidhamma debates.

- Stoic ethics of detachment and universal brotherhood mirror Buddhist equanimity (upekkhā) and compassion (karuṇā).

Thus Aśoka’s missions were not just the export of ideas but the beginning of a global spiritual dialogue.

3.10 Aśoka’s Universal Vision

Aśoka saw himself as a Dharmarāja — not merely an Indian king but a cosmic ruler responsible for the moral welfare of the whole world.

In Rock Edict XII, he writes:

“All sects should dwell everywhere, for all seek self-control and purity of mind.

Whoever praises his own sect and disparages another, wholly out of devotion to his own, with the view of glorifying his own sect, does the greatest harm to his own sect.”

This is one of history’s first declarations of religious pluralism and interfaith respect.

3.11 The Wheel Rolls West

The Buddha’s Dhammacakka — the Wheel of Dhamma — was not a static symbol. Under Aśoka, it became a vehicle that literally rolled across deserts and seas, carried by missionaries who saw themselves as world-healers.

Some seeds were lost, but others took root — in Alexandria, in Qumran, in the desert monasteries of Egypt — eventually flowering into Christian monasticism and mystical traditions.

3.12 Why This Matters for Christianity

If the Therapeutae are indeed the direct descendants of Aśoka’s missionaries, then Christianity’s contemplative DNA may contain a Buddhist strand.

When John the Baptist called Israel to repentance in the wilderness, he stood in a landscape already seeded with communities of renunciation and meditation.

When Jesus taught his disciples to fast, pray, and take nothing for their journey, he was speaking into a world where the idea of the renunciant-healer was already familiar.

3.13 Preparing for the Next Section

Our next step is to look more closely at the Therapeutae themselves — the healers of the soul, the first Western contemplatives — and how their legacy passed into the Essenes and early Christian spirituality.

4. The Therapeutae of Alexandria — Heirs of the Elders’ Path

When Emperor Aśoka sent forth his missionaries to the four quarters of the known world, he was not merely spreading a religion — he was planting a way of life. What grew on the shores of Lake Mareotis, just outside the bustling Hellenistic city of Alexandria, was one of the most fascinating fruits of that sowing: the Therapeutae.

They were not a footnote to history. They were living heirs of the Theravāda Saṅgha, a Western embodiment of the path of purification. Their existence shows that the Dhamma could cross cultural and linguistic boundaries, take root in foreign soil, and flourish among seekers who had never heard the Pāli Canon — but who recognized truth when they encountered it.

The Therapeutae are important not only as a historical curiosity but as a proof of universality: they show that the path of disenchantment (nibbidā), dispassion (virāga), purification, and liberation (vimutti) is not limited to one culture but is open to all humanity.

4.1 Alexandria: The Meeting Place of Worlds

To understand the Therapeutae, we must first picture Alexandria in the 3rd–1st centuries BCE. Founded by Alexander the Great, Alexandria became the intellectual capital of the Mediterranean world:

- The Great Library housed hundreds of thousands of scrolls from across the known world — Greek philosophy, Egyptian wisdom, Hebrew scriptures, Persian science, Indian treatises.

- The Museum was a center for research and teaching, where scholars debated astronomy, medicine, and metaphysics.

- The Lighthouse of Pharos, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, was a beacon to travelers — a fitting symbol of the “light of wisdom” that was gathering there.

Into this cosmopolitan city came the emissaries of Aśoka, carrying the wheel of the Dhamma. According to the Mahāvaṃsa and Aśoka’s own rock edicts, they were sent to the lands of the Yonas (Greeks) and even to Egypt. The idea that Indian bhikkhus walked the streets of Alexandria is not far-fetched — inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic survive from Aśokan India, showing that communication across cultural frontiers was happening.

4.2 Philo of Alexandria — Our Witness

Our most detailed account of the Therapeutae comes from Philo Judaeus of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE), a Jewish philosopher deeply committed to the Torah yet fascinated by Greek philosophy. In his treatise De Vita Contemplativa (“On the Contemplative Life”), Philo paints a picture of a community that had chosen a life of renunciation, meditation, and allegorical study.

He writes:

“They have left their property to their sons, their daughters, or other kinsmen, voluntarily abandoning the wealth they once possessed, so that they might be no longer enslaved by any of the passions of the soul, but free to contemplate the divine.”

This is a remarkable statement. It describes nekkhamma — the voluntary renunciation of the world, not out of despair but to gain freedom from passion. This is exactly the first step of the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path: Right View leading to Right Intention, which includes renunciation as a positive choice.

4.3 A Life of Discipline and Purification

Philo gives us a detailed description of their life:

- Voluntary Poverty: Each member gave up their possessions, leaving their inheritances to family or dependents, and withdrew to live in small huts near Lake Mareotis.

- Solitude and Silence: Six days a week they remained in seclusion, meditating, studying, and writing. They emerged only for prayer or essential needs.

- Fasting and Restraint: They ate simple food, often once per day after sunset, and viewed hunger as a tool for taming the passions.

- Celibacy and Chastity: Many remained lifelong celibates. Those who had been married renounced marital relations after joining the community, redirecting their energies to contemplation.

- Scriptural Allegory: They studied the Hebrew Scriptures but did not interpret them literally. They sought the hidden, allegorical meaning — the spiritual sense beyond the letter.

This lifestyle was not mere philosophy. It was ascetic practice (tapas in Sanskrit), aimed at transforming the mind and purifying the heart.

Reflection — Your Own Solitude

When was the last time you gave yourself a day of silence?

Could you step away — even for an afternoon — from noise, screens, conversation, and simply sit by the “shore of your own Lake Mareotis,” allowing the heart to settle?

The Therapeutae teach us that solitude is not loneliness but a laboratory for liberation.

4.4 The Weekly Assembly — A Western Uposatha

Philo describes how, on the seventh day, they gathered for a communal festival:

- The elders sat according to seniority.

- Sacred texts were read aloud and interpreted allegorically.

- Hymns were sung antiphonally — men and women answering each other in a dialogue of praise.

- The community shared a simple meal.

- They kept vigil through the night, chanting and singing until dawn, at which point they celebrated with joy.

This rhythm mirrors the uposatha day of the Theravāda Saṅgha:

- Communal recitation of the Pātimokkha (disciplinary code).

- Dhamma talks and exhortation to renewed practice.

- Meditation and vigil through the night.

Even their preference for human voice over musical instruments parallels the Buddhist use of chant as a meditative act — not entertainment but contemplation.

4.5 Parallels with the Theravāda Saṅgha

| Therapeutae (Lake Mareotis) | Theravāda Saṅgha (India) |

|---|---|

| Abandoned wealth, lived in huts | Pabbajjā: Going forth into homelessness |

| Practiced celibacy and purity | Brahmacariya, Pātimokkha discipline |

| Spent six days in solitude | Jhāna and vipassanā retreat |

| Simple diet, fasting | One-meal-before-noon rule |

| Weekly communal assembly | Fortnightly uposatha ceremony |

| Allegorical Scripture interpretation | Search for paramattha-sacca (ultimate truth) |

| Hymn-singing, all-night vigils | Chanting suttas, paritta, all-night practice |

This is not merely a vague similarity. It is a specific transposition of the saṅgha’s rhythm into a Jewish–Egyptian setting.

4.6 The Name — Therapeutae and Thera-putta

The name Therapeutae is commonly translated “healers,” from Greek therapeuō — to heal, to serve, to worship.

But it may also be a rendering of the Pāli term thera-putta — “sons (or children) of the elders.”

- The theras were the senior monks, the guardians of the original teaching.

- Their followers, the thera-puttas, carried forward the discipline.

If the missionaries from India described themselves as thera-puttas, Greek listeners may have heard something like therap-utae — and the term may have been naturalized into Greek with its double meaning intact: those who serve and those who heal.

Thus the name itself may be evidence of their Theravāda origin.

4.7 The Healing Dimension — Corrected

Philo calls them “physicians of the soul.” Here we see the perfect resonance with the Buddha’s role as the Great Physician (Bhesajja-guru).

But this must be understood correctly:

- The Buddha did not promise annihilation.

- He declared that there is a state beyond the reach of suffering — amata-dhātu (the deathless element).

- He described a path of purification that leads there.

- He invited beings to walk it for themselves.

- The cure is not extinction but freedom:

- Nibbāna literally means “cooling,” the quenching of the fires of greed, hatred, and delusion.

- The citta becomes cool, luminous, undefiled.

- It stands free, unshaken — beyond the reach of birth and death.

The Therapeutae used fasting, prayer, and meditation as therapeia, therapy for the soul. Their goal was not mere moralism but the restoration of harmony, the return of the soul to its true condition.

Reflection — The Medicine of the Path

Where do you feel the “heat” of the three fires — rāga, dosa, moha — in your own mind?

What single step could you take this week to cool the heart and let it become clear?

4.8 Women and the Fourfold Assembly

Philo notes that women were full participants:

- They lived in celibate dwellings.

- They joined in chanting and study.

- They were honored as co-practitioners.

This is significant because it shows that bhikkhunī-style communities existed in the West centuries before Christian nuns. It suggests that the Western mission carried both monks and nuns, preserving the complete fourfold assembly.

4.9 Jewish Mysticism Meets Theravāda

The Therapeutae were likely not imported monks but a fusion community — Jewish mystics who encountered the Theravāda discipline and saw in it a perfect method for seeking God.

- Hasidim (pious ones) of the Maccabean period were already practicing strict purity.

- Nazirites took vows of celibacy, abstinence, and separation from society.

- Prophets like Elijah and Elisha had schools in the wilderness.

When these currents met the structured monasticism of the saṅgha, a new synthesis was born — Torah devotion wedded to meditative discipline.

4.10 Their Impact on Later History

The Therapeutae’s influence can be traced forward into:

- The Essenes of Qumran, with their communal discipline and apocalyptic expectation.

- John the Baptist, whose call to repentance and life of fasting echoes their ethos.

- The Desert Fathers, who created Christian monasticism in Egypt — perhaps on the very soil where the Therapeutae once lived.

- Christian mystical theology, which continued the therapeutic model of religion — sin as sickness, grace as medicine.

Eusebius of Caesarea even claimed that the Therapeutae were the first Christian monks — a claim not historically exact but revealing of how much the Christian imagination owed to them.

4.11 Why They Matter Today

The Therapeutae stand as a signpost pointing both backward and forward:

- Backward — reminding us that Aśoka’s mission reached Egypt, that the Dhamma’s universality was already known.

- Forward — showing us that the path of purification is always open, always available to those who choose to walk it.

In an age distracted by endless noise, they call us back to solitude, simplicity, and the healing of the mind.

They are not merely a memory but a model — one that can inspire new saṅgha-like communities today: places of renunciation, meditation, and inner transformation.

5. From Therapeutae to Essenes

If the Therapeutae were the first flowering of the Dhamma on Western soil, the Essenes were the next generation — a transplanted branch, growing in the rocky hills of Judea. The story of how the contemplative life of Alexandria made its way back to Palestine is a story of migration, longing, and a people seeking purity in an age of political and spiritual crisis.

5.1 The Jewish Diaspora and the Road Back to Judea

In the centuries following the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE), Jews were scattered throughout the Near East — Babylon, Persia, Egypt, and later the Hellenistic cities founded by Alexander the Great. Alexandria became one of the largest Jewish centers outside of Palestine, with perhaps a third of its population Jewish by the 3rd century BCE.

It was here, in the great city of Alexandria, that Jewish scholars produced the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible — a work that profoundly shaped Jewish and Christian thought.

It was also here that some Jews came into contact with the Therapeutae, or became Therapeutae themselves. The discipline they learned — fasting, celibacy, meditation, allegorical reading of Scripture — they carried back to Judea.

5.2 A Time of Crisis: The Second Temple Period

The return of this discipline coincided with a time of great turbulence in Judea. The Second Temple had been rebuilt, but the Jewish nation was under foreign rule — first the Persians, then the Greeks, then the Seleucids, and eventually the Romans.

Religious life had become increasingly polarized:

- The Sadducees, priestly aristocrats, collaborated with foreign rulers and controlled the Temple.

- The Pharisees, popular teachers of the Law, emphasized oral tradition and strict observance.

- The Zealots advocated violent resistance and awaited a militant Messiah.

In this charged atmosphere, a group of mystics withdrew from public life altogether, retreating to the wilderness to form their own pure community. These were the Essenes.

5.3 Who Were the Essenes?

Our sources for the Essenes are threefold:

- Philo of Alexandria, who admired them and described their communal, ascetic life.

- Flavius Josephus, the Jewish historian who called them one of the “three sects of Judaism” alongside Pharisees and Sadducees.

- Pliny the Elder, who located them near the Dead Sea, “without women, without money, and the palm trees their only company.”

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran in 1947 gave us a treasure trove of primary texts, revealing the theology, rituals, and daily discipline of this community.

5.4 Parallels Between Essenes and Therapeutae

The Essenes shared with the Therapeutae a striking set of characteristics that go beyond coincidence:

| Therapeutae (Alexandria) | Essenes (Qumran) |

| Renounced property, lived simply | Shared all possessions in common |

| Practiced celibacy or strict chastity | Most members celibate, marriage only for select branches |

| Daily prayer, meditation, Scripture study | Daily reading of Torah and hymns |

| Fasting, dietary discipline | Ritual meals, restricted diet |

| Weekly communal gathering | Regular assemblies, solemn councils |

| Allegorical interpretation of texts | Pesher method (commentaries revealing hidden meaning) |

| Focus on inner healing, purifying passions | Emphasis on purity, washing rites, moral cleansing |

Both groups saw themselves as a remnant — a purified Israel, a holy community preparing the way for divine intervention.

5.5 The Qumran Community: A Desert Monastery

The Qumran settlement on the northwest shore of the Dead Sea appears to have been a self-sufficient monastery:

- Archaeologists have found communal dining halls, ritual baths (mikva’ot), and a scriptorium where scrolls were copied.

- The Community Rule scroll outlines a strict initiation process: a probationary year, then full membership, then sharing of property.

- Severe discipline was enforced: expulsion for grave sins, penances for lesser infractions.

This is remarkably similar to the upasampadā process of the Saṅgha, where candidates train as novices before full ordination and are subject to the disciplinary code.

5.6 Apocalyptic Expectation

The Essenes lived in expectation of an imminent cosmic battle between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness.”

Their War Scroll describes this in detail: angelic hosts fighting alongside the community, the final purification of Israel, and the establishment of a righteous kingdom.

This apocalyptic hope parallels the Buddhist prophecy of Metteyya, the Future Buddha who will appear when the world has fallen into darkness to renew the Dhamma.

In both cases, the contemplative community sees itself as preparing the world for the arrival of a redeemer.

5.7 Purity and Ritual Baths

The Essenes were fanatical about ritual purity, immersing themselves daily in water. Archaeologists have uncovered dozens of mikva’ot at Qumran.

This mirrors the Buddhist practice of purification before communal ceremonies, and even the symbolic bathing of the Buddha in some traditions.

It also anticipates Christian baptism, which John the Baptist — himself often associated with the Essenes — preached in the Jordan River.

5.8 Communal Meals

At Qumran, meals were sacred: members ate in silence, in order of seniority, after prayers of blessing.

Josephus describes how the Essenes “partake of food with one another in a state of purity, as though it were some sacred rite.”

This parallels the bhikkhu communal meal, where food is received mindfully, eaten in silence, and regarded as alms — a sacrament of dependence and gratitude.

Later, this ethos would shape the Christian Eucharist, which likewise combines thanksgiving, communal unity, and eschatological hope.

5.9 The Teacher of Righteousness

Among the Dead Sea Scrolls we find references to a mysterious figure called the Teacher of Righteousness — a prophetic leader who founded the community, interpreted Scripture, and suffered persecution from the “Wicked Priest.”

Some scholars suggest he may have been a Zadokite priest who broke with the Jerusalem hierarchy.

But in light of our wider narrative, the Teacher of Righteousness could also be seen as a Jewish counterpart to the Buddhist Elder — a reformer who, like a thera, preserves the true teaching and passes it on to disciples.

5.10 Women in the Community

Although most Essenes were male, some branches included women who shared the same vows and discipline. This is significant: it suggests a bhikkhunī-like presence in early Jewish mysticism, reinforcing the idea that the Therapeutae — where men and women practiced together — influenced the Essenes.

5.11 The Essenes and John the Baptist

The connection between the Essenes and John the Baptist has long been noted:

- Both lived in the wilderness, near the Jordan/Dead Sea region.

- Both emphasized repentance, purity, and the coming kingdom.

- Both practiced baptism-like rites.

If John was trained among the Essenes, as some scholars suggest, then his fiery preaching was the public face of a centuries-old contemplative tradition that began in Alexandria and ultimately in India.

5.12 The Dead Sea Scrolls as Witness

The Dead Sea Scrolls provide us with an unparalleled window into this community’s inner life:

- Hymns of thanksgiving that sound like Buddhist gāthās — poetic meditations on the soul’s struggle and God’s mercy.

- Rulebooks and disciplinary codes that read like a Jewish Vinaya.

- Apocalyptic visions that reveal a community convinced that it stood at the hinge of history.

These texts show a fusion of Torah devotion with a monastic rhythm of life — a way of being that may owe as much to Therapeutae discipline as to Israel’s prophetic heritage.

5.13 The Wider Impact

The Essenes’ influence did not die with Qumran’s destruction in 68 CE.

- Their texts were copied and preserved, eventually surfacing as part of the Christian and Rabbinic imagination.

- Their model of community life inspired Christian monasticism in Egypt (the Desert Fathers) and beyond.

- Their vision of purity and kingdom shaped Jesus’ own proclamation of the Kingdom of Heaven.

Thus, the Essenes form a bridge between the Therapeutae and the earliest Christians, preserving the therapeutic and contemplative ethos through which the Buddha’s message entered Western history.

5.14 Spiritual Continuity

What we see in this lineage is not a series of disconnected phenomena but a continuous stream:

- Aśoka’s missionaries bring the Dhamma west.

- The Therapeutae embody it in Alexandria, blending it with Jewish mysticism.

- The Essenes carry it into the Judean desert, living as a purified remnant.

- John the Baptist and Jesus inherit this desert tradition, bringing its essence into the heart of Judaism.

In this way, the wheel of Dhamma did not stop turning in Egypt — it rolled into Judea, into Galilee, and eventually into the Christian Church.

5.15 Why This Matters

Recognizing the Essenes as spiritual descendants of the Therapeutae reframes the origins of Christianity:

- It shows that Jesus’ world was not spiritually barren but already rich with ascetic and contemplative traditions.

- It suggests that the ethical and mystical ideals of Buddhism — renunciation, compassion, inner purification — were part of the soil from which Christianity sprang.

- It invites a renewed dialogue between East and West, showing that these traditions have always been siblings rather than rivals.

6. John the Baptist and the Preparation of the Way

John the Baptist stands at a unique threshold in history. He is both the last prophet of Israel and the herald of something utterly new. His cry in the wilderness, “Prepare the way of the Lord!”, is more than a call to moral reform — it is the culmination of centuries of spiritual preparation, stretching from Babylon to Alexandria to the shores of the Dead Sea.

Seen through the lens of the Therapeutae–Essenic lineage, John becomes not merely a lone ascetic but the public voice of a contemplative tradition that had been quietly maturing for centuries.

6.1 Zechariah and Elizabeth: Parents of the Forerunner

The Gospels tell us that John’s parents, Zechariah and Elizabeth, were “righteous before God, walking blamelessly in all the commandments and statutes of the Lord” (Luke 1:6). This is not a casual statement — it suggests that they were part of a highly disciplined sect, committed to purity and Torah observance at the strictest level.

Some scholars argue that Zechariah, as a priest serving in the Temple, may have been part of the Zadokite priestly line, the very lineage that the Essenes claimed to represent in opposition to the Temple establishment. The Qumran scrolls refer repeatedly to the “Sons of Zadok,” the faithful priests who would preserve the covenant until the end of days.

Elizabeth, too, is described as “of the daughters of Aaron,” which would make John a descendant of the priestly class on both sides — perfectly placed to inherit and transmit a priestly–prophetic mission.

6.2 A Child of Promise

John’s birth narrative is steeped in prophetic overtones:

- His father Zechariah receives an angelic visitation in the Temple, announcing that Elizabeth will conceive despite her old age.

- The angel Gabriel declares that John will be “great before the Lord,” that he will “drink neither wine nor strong drink,” and that he will be “filled with the Holy Spirit from his mother’s womb” (Luke 1:15).

This abstinence from wine may be a sign that John was consecrated as a Nazirite — a person under a vow of holiness, dedicated to God, avoiding strong drink, refraining from cutting hair, and avoiding ritual impurity.

This is entirely consistent with Essene discipline, which also forbade intoxicants, enforced strict purity, and treated their members as living temples of holiness.

6.3 Growing Up Near the Wilderness

Luke 1:80 tells us that John “grew and became strong in spirit, and he was in the wilderness until the day of his public appearance to Israel.”

The wilderness was not merely a place of geographical isolation — it was the training ground of prophets. Moses encountered God on Sinai, Elijah heard the still small voice in the desert, and Israel was forged in the forty years of wandering.

For John, the desert was also the home of the Essene settlements, particularly at Qumran and along the Dead Sea. The parallels are too strong to ignore:

- The Essenes raised children in their community when their parents offered them up.

- They trained initiates for years before admitting them to full membership.

- They had a rhythm of prayer, immersion, and Scripture reading that shaped every hour of the day.

It is not difficult to imagine John spending his youth among these desert mystics, learning their ways, fasting with them, and absorbing their apocalyptic expectation.

6.4 Ritual Immersions and the Call to Purity

John’s signature practice — baptism in the Jordan River — is a direct continuation of the Essene practice of daily immersion (tevilah) in ritual baths (mikva’ot).

But John did something revolutionary: he took this ritual out of the community and offered it to the masses.

- The Essenes immersed daily for personal purity.

- John immersed once as a public sign of repentance and preparation for the coming kingdom.

This was a democratization of Essene spirituality — opening the door for all of Israel to participate in the purification necessary to receive the Messiah.

6.5 The Garb of a Prophet

John is described as wearing “a garment of camel’s hair and a leather belt around his waist” (Mark 1:6). This was not a fashion statement — it was a deliberate echo of the prophet Elijah, who wore similar garb (2 Kings 1:8).

Elijah was the great reformer and miracle-worker of Israel, who confronted kings and called the nation back to covenant fidelity. The Essenes saw themselves as a “community of Elijah,” preparing for the final battle between light and darkness.

By taking on Elijah’s mantle, John placed himself squarely in this prophetic tradition — one that was not merely rhetorical but deeply ascetic, shaped by solitude, fasting, and prayer.

6.6 Fasting and Simplicity

John’s diet of “locusts and wild honey” (Mark 1:6) is another sign of his ascetic life. Locusts were among the few kosher insects permitted by the Torah, and wild honey required foraging — no cultivated luxury foods for John.

This diet mirrors the Essenes, who were known for eating simple, ritual meals — often bread, salt, and water — and for abstaining from meat and wine except on special occasions.

In Buddhist terms, John lived like a dhutaṅga monk, practicing voluntary austerities to strip away attachment and intensify his spiritual power.

6.7 The Fire of Saṃvega

The Buddhist term saṃvega refers to the sense of urgency that arises when one sees the futility of worldly life and longs for liberation.

John embodies saṃvega in the Jewish tradition. His preaching is urgent, fiery, uncompromising:

“Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand!” (Matthew 3:2)

He calls his hearers to radical transformation — to share clothing and food with the poor, to abandon exploitation, to be baptized as a sign of new life.

This is precisely what the Essenes were doing in the desert — purifying themselves for the coming visitation of God.

6.8 The Bridge Between Traditions

John is thus the bridge between the hidden contemplative life of the Essenes and the public mission of Jesus.

- From the Essenes he inherits the emphasis on purity, repentance, and apocalyptic expectation.

- From the Therapeutae (through the Essenes) he inherits the practice of renunciation, fasting, and a life ordered around the healing of the soul.

- From the prophets of Israel he inherits the fire of moral confrontation, the willingness to rebuke kings, and the vision of a coming kingdom of righteousness.

John’s role is transitional: he stands with one foot in the Old Covenant and one foot pointing toward the New.

6.9 The Baptism of Jesus

John’s greatest moment is the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan. Here the streams converge:

- The Essene discipline meets the Nazarene carpenter.

- The waters of purification become the waters of initiation into a mission that will transform the world.

In this moment, Jesus affirms the entire contemplative tradition that led to John — yet he will take it further, out of the desert and into the villages, out of sectarian boundaries and into universal proclamation.

6.10 John’s Final Witness

John’s life ends in martyrdom — imprisoned by Herod Antipas for condemning his unlawful marriage, and eventually beheaded.

His death is not merely a political tragedy but a spiritual sign: the old order is passing, the new is at hand.

Jesus himself honors John as the greatest of those born of women, yet says that “the least in the kingdom of heaven is greater than he” (Matthew 11:11) — meaning that John represents the summit of preparation, but the kingdom itself will surpass even his highest vision.

6.11 The Continuing Influence of John’s Movement

Even after his death, John’s disciples continued to exist as a distinct movement, as the book of Acts records (Acts 19:1–7). Some of them became followers of Jesus; others remained separate.

This shows that John’s mission was powerful enough to sustain a community on its own — a testament to the spiritual energy of the Essene–Therapeutae tradition that shaped him.

6.12 The Desert as Archetype

John’s story reveals the desert as the archetypal place of preparation.

In Buddhist terms, the desert is the arañña — the wilderness where bhikkhus go to break attachment, confront fear, and deepen concentration.

In Jewish and Christian terms, the desert is the place where God’s people are stripped bare, taught dependence, and prepared for revelation.

Thus John’s desert sojourn is not incidental but essential — the necessary stage before the advent of the Messiah.

6.13 The Universal Pattern

John’s life shows us a universal pattern of spiritual renewal:

- Withdrawal from a corrupt world

- Discipline, fasting, and purification

- Apocalyptic or transcendent vision

- Public proclamation and call to transformation

- Costly witness — even unto death

This pattern appears in Buddhist arahants, Hindu rishis, Sufi saints, Christian monks, and prophetic reformers in every age.

6.14 Preparing the Reader

In our narrative, John the Baptist functions as the threshold figure — the one who stands at the end of one world and the dawn of another.

He is the last heir of the Therapeutae and Essenes, the last great prophet of Israel, and the first to point to Jesus as “the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (John 1:29).

For the reader, John represents the inner work of preparation:

- The willingness to leave the old life

- The courage to confront one’s own impurity

- The urgency to seek the kingdom first

Only then can we, too, be ready to meet the one who brings the deathless way.

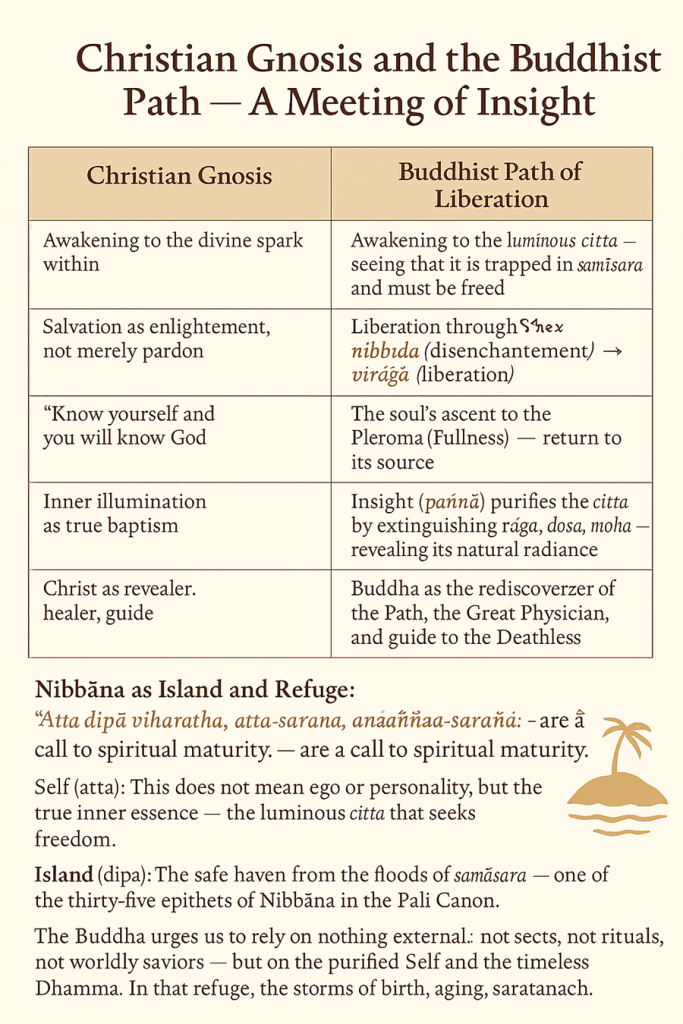

7. Gnosis and the Early Christians

When we reach the early centuries of Christianity, we find a vibrant and often contested landscape. The Jesus movement had begun to spread across the Roman Empire, taking root in Jewish, Greek, and Roman soil. The key question was not merely political or ritual but deeply existential:

What does it mean to be saved?

For some, salvation was primarily juridical — a matter of guilt removed, sins forgiven, and standing restored before God. But for others, salvation was therapeutic and illuminative — a process of healing the soul, purifying the mind, and entering into direct communion with divine life.

This second stream is what we now call Gnosis — not intellectual knowledge but transformative knowing. Gnosis is the awakening of the soul to its true nature and destiny, the insight that heals and liberates.

7.1 What is Gnosis?

The Greek word gnōsis means “knowledge,” but in the early Christian mystical tradition it points to a deeper reality — direct acquaintance with truth:

- Not book-learning but first-hand seeing.

- Not mere speculation but experiential vision.

- Not only believing in God but perceiving, even participating in, the divine life.

This resonates with the Buddhist term vipassanā — insight into reality as it truly is (yathābhūta-ñāṇadassana). Both traditions affirm that this insight is not theoretical but transformative, the key to liberation.

7.2 The Therapeutic Dimension of Gnosis

For the Gnostics, humanity’s problem was not simply moral guilt but spiritual sickness — ignorance (agnōsia), forgetfulness, bondage to lower powers. Their language was diagnostic and curative:

- The soul is asleep — it must be awakened.

- The inner spark is buried — it must be freed.

- The mind is clouded — it must be illuminated.

The Buddha gave a similar diagnosis:

- The citta is afflicted by rāga, dosa, moha (craving, aversion, delusion).

- The cure is not punishment but purification — uprooting these defilements at the root.

- The Eightfold Path functions as a regimen — ethical, mental, and wisdom training — leading to liberation.

Thus Gnosis, like the Dhamma, is not a mere belief system but a therapy for existence, aimed at restoring the soul to clarity and freedom.

7.3 The Gospel of Thomas: A Gnostic Window

One of the most revealing texts from early Christianity is the Gospel of Thomas, discovered among the Nag Hammadi codices in 1945. Rather than a narrative, it is a collection of 114 sayings of Jesus. Many echo the canonical gospels, while others are more cryptic, contemplative, and inwardly focused.

“The kingdom is inside you, and it is outside you. When you come to know yourselves, then you will be known, and you will realize that you are children of the living Father.” (Thomas 3)

This is not the language of legal pardon — it is the language of self-knowledge leading to liberation. It parallels the Buddha’s repeated insistence that liberation comes from seeing for oneself — not from reliance on external saviors or rituals.

7.4 Light Imagery and Enlightenment

Gnostic texts often speak of light as the symbol of knowledge: the light that dispels darkness, reveals what is hidden, and guides the soul home.

Buddhism too uses this imagery: enlightenment (bodhi) as the dawning of wisdom that scatters the darkness of ignorance.

- In Gnostic cosmology, the material world is under shadow until the light of knowledge breaks through.

- In Buddhism, beings wander in the darkness of delusion until the light of wisdom (paññā) leads them to Nibbāna.

Both traditions affirm that seeing clearly is itself the doorway to freedom.

7.5 The Therapeutic Path

The Gnostic way of salvation was practical, not merely doctrinal:

- Ascetic discipline: celibacy, simplicity, renunciation — just as the Therapeutae and Essenes lived.

- Meditative prayer: contemplation, invocation, silent interior turning toward the divine.

- Purifying rites: baptism, anointing — not as ends but as initiations into a deeper transformation.

- Interpretive practice: reading sacred texts as allegories of the soul’s ascent.

This mirrors the Buddhist path of practice:

- Sīla: cleansing conduct.

- Samādhi: stabilizing and concentrating the mind.

- Paññā: seeing reality as it is — leading to nibbidā (disenchantment), virāga (dispassion), and finally vimutti (liberation).

7.6 Wisdom as Inner Clarity

Where some Gnostic systems personified Wisdom as Sophia, a cosmic being who must be redeemed, the Theravāda path treats wisdom not as a deity but as a quality of the purified mind itself.

Paññā is not mythic but experiential: the clear seeing that cuts through delusion. When the mind is purified, it recognizes the three characteristics (anicca, dukkha, anattā) and naturally turns away from the world — leading to disenchantment, dispassion, and release.

This is a crucial distinction: liberation is not mythic drama but mental purification and transcendence.

7.7 Salvation as Remembering

A key theme in Gnostic texts is anamnesis — remembering.

But here “remembering” is not just mental recollection; it is re-membering — putting the soul back together, returning to wholeness.

- The soul must remember where it came from — and rejoin its Source.

- The divine spark must recall its origin in the Fullness (Pleroma).

- Forgetfulness is the cause of bondage; remembering is the first step toward homecoming.

This finds a close echo in the Buddha’s Dhamma:

- Sati (mindfulness) literally means “memory,” the act of recollecting what is true.

- But its highest function is not just awareness of the present — it is remembering the Path, remembering the goal, remembering that the citta is meant for freedom.

- When the mind “remembers” its true nature, it becomes disenchanted with the world (nibbidā), grows dispassionate (virāga), and is finally released (vimutti).

Thus, salvation as “remembering” is salvation as re-membering — reintegration with the true Refuge:

- For the Gnostic Christian, it is rejoining the Father, the Kingdom of Heaven.

- For the Buddhist, it is returning to Nibbāna-dhātu, the deathless Island, the home of manussa, where there is no more aging or death.

7.8 Conflict and Continuity

Though the institutional church later condemned many Gnostic groups, their contemplative and therapeutic emphasis did not disappear. It flowed into:

- Early Christian monasticism — with its ascetic life, vigils, fasting, and prayer.

- Mystical theology — emphasizing direct experience of God (hesychasm, the desert fathers).

- Allegorical interpretation — treating Scripture as a path of ascent, not merely literal history.

In this way, the therapeutic heart of Gnosis continued, even within orthodox Christianity.

7.9 The Buddha and the Revealer

Both Buddhism and Gnostic Christianity portray the great teacher as a revealer — one who awakens what is already latent.

- The Buddha is the rediscoverer of the path to the deathless, showing how to extinguish defilements and cross the flood.

- The Gnostic Christ is the Logos who reminds the soul of its true home and calls it to return.

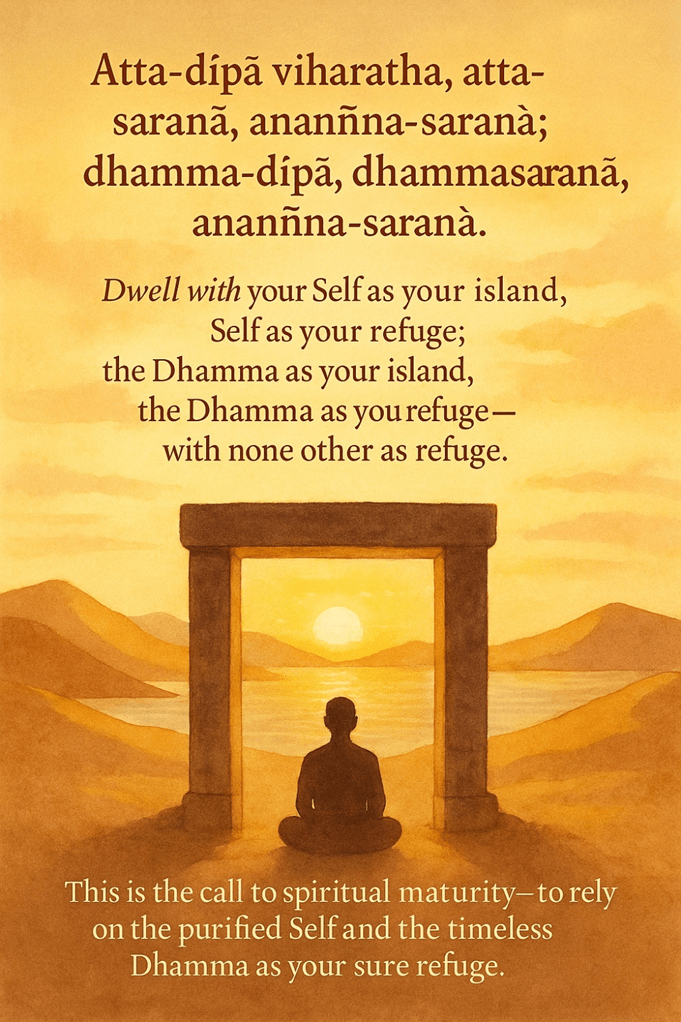

Here we may recall the Buddha’s own words:

“Atta-dīpā viharatha, atta-saraṇā, anañña-saraṇā; dhamma-dīpā, dhamma-saraṇā, anañña-saraṇā.”

Dwell with your Self as your island, Self as your refuge; the Dhamma as your island, the Dhamma as your refuge — with none other as refuge.

This is a call to spiritual maturity: trust the purified Self (citta) and the Dhamma, not external authorities.

7.10 The Therapeutic Model of Salvation

When we view salvation through this lens, it becomes clear:

- Sin is sickness, not simply crime.

- Grace is healing medicine, not mere legal pardon.

- Liberation is purification, not annihilation.

The Buddha as the Great Physician and Jesus as the Good Shepherd both lead toward healing the roots of bondage, not merely declaring amnesty.

7.11 Gnosis as Inner Baptism

Some Gnostic writings speak of an “inner baptism” — a fire or light that purifies the soul beyond the external rite.

This aligns with the Buddhist recognition that outward rituals are not enough: the mind must be purified at the root through insight, leading to nibbidā → virāga → vimutti.

7.12 Implications for Today

Recovering this contemplative dimension is not about reviving heresy but about reclaiming the heart of the path:

- Awakening to direct experience of truth.

- Healing the poisons that cloud the mind.

- Crossing over to the true refuge — the deathless, the Island, Nibbāna-dhātu.

7.13 A Shared Human Quest

When seen in this light, Gnosis and the Buddhist path converge on a universal cry:

- To see reality as it is.

- To be freed from delusion.

- To find the safe haven beyond the storms of saṃsāra.

Whether one calls it the Kingdom, the Pleroma, or Nibbāna-dhātu, the end is the same: liberation from death, entry into the deathless.

8. The Legacy: Monasticism and Modern Therapy

The contemplative and therapeutic stream we have traced — from the Therapeutae of Alexandria, to the Essenes of Qumran, to John the Baptist and the early Gnostic Christians — did not vanish with the closing of the first century. Instead, it continued to flow, shaping Christian monasticism and even influencing how the modern world understands the healing of the mind.

This chapter explores that legacy — how the early currents of renunciation, meditation, and soul-healing became institutionalized in monasteries, preserved through centuries of upheaval, and eventually gave birth to new sciences of the psyche that still echo the ancient work of purification.

8.1 The Desert Fathers and Mothers

In the third and fourth centuries CE, a remarkable movement arose in the deserts of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine: men and women left their cities, their families, and their wealth to live as hermits, ascetics, and contemplatives.

These were the Desert Fathers and Mothers — the first Christian monastics.

- Anthony the Great (251–356 CE): Often called the “father of monasticism,” Anthony retreated into the desert after hearing the gospel text: “Go, sell what you possess, and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven; and come, follow me.” (Mark 10:21). He lived a life of solitude, prayer, fasting, and manual labor — eventually attracting disciples who gathered around him as a community.

- Macarius, Pachomius, Amma Syncletica, and others: Formed schools of ascetic practice, teaching novices to purify their hearts through silence, humility, and vigil.

Their lifestyle is strikingly parallel to the Theravāda arahant ideal:

- Renunciation: Leaving behind possessions, status, and worldly ties.

- Solitude: Seeking silence and simplicity as a way to confront one’s passions directly.

- Meditation: Continuous prayer (oratio continua), the Christian equivalent of bhāvanā (mental cultivation).

- Therapeutic aim: The Desert Fathers spoke constantly of apatheia — not apathy, but freedom from the tyranny of passions, the very same goal as overcoming rāga, dosa, moha.

8.2 Monasticism as a Continuation of the Therapeutae

The parallels with the Therapeutae of Alexandria are too strong to ignore.

Philo’s description of the Therapeutae — living near Lake Mareotis, renouncing possessions, meditating, singing hymns, meeting weekly — could be applied almost word-for-word to the Desert Fathers.

Indeed, some scholars argue that the Desert Fathers are the direct inheritors of the Therapeutae:

- The Therapeutae disappear from historical record just as Christian monasticism appears in the same geographical region.

- Both emphasize celibacy, fasting, and allegorical interpretation of Scripture.

- Both see themselves as physicians of the soul, healing through contemplation.

If this is true, then Christian monasticism is not a late invention but a direct continuation of the contemplative movement seeded by Aśoka’s missionaries, carried through the Jewish mystics, Essenes, and early Christians.

8.3 The Rule of St. Benedict and Western Monasticism

By the sixth century, monasticism spread beyond the deserts into Europe, where it became more structured. St. Benedict of Nursia (480–547 CE) wrote his famous Rule of Life, which became the foundation for Western monasticism.

Benedict’s Rule includes:

- Stability: Remaining in one monastery for life — a vow not unlike the Theravāda monk’s full ordination commitment.

- Obedience: Submission to the abbot, reminiscent of the Buddhist upajjhāya–saddhivihārika (teacher–disciple) relationship.

- Conversatio morum: Ongoing conversion of life — a commitment to continual purification of mind and heart.

- Ora et Labora: “Pray and work” — balancing meditation with productive labor, just as Buddhist monasteries balance meditation with alms-round and teaching.

These monasteries became centers of learning and preservation: copying manuscripts, keeping libraries, offering hospitality — much like ancient Buddhist vihāras, which served as universities and centers of culture.

8.4 Carmelites, Cistercians, and the Contemplative Orders

As Christianity matured, new monastic orders arose, each emphasizing deeper contemplation.

- Cistercians (11th c.): Advocated radical simplicity, plain architecture, silence, and manual labor.

- Carthusians: Perhaps the most austere of all, living in near-total silence and solitude.

- Carmelites (12th c.): Focused on meditative prayer and interior union with God — producing mystics like St. John of the Cross and St. Teresa of Avila.

These movements demonstrate that the therapeutic, meditative dimension of the Christian path never died. It evolved, adapted, and flourished — often in tension with more institutional and political forms of the Church.

8.5 Apatheia, Hesychia, and the Purification of the Heart

The Desert Fathers spoke of three stages of the spiritual life:

- Katharsis (Purification): Cleansing the soul from passions and sins.

- Photisis (Illumination): Receiving the light of divine knowledge.

- Theosis (Union): Participation in the divine life.

This threefold path mirrors the Buddhist triad of sīla → samādhi → paññā, leading to vimutti.

Key terms:

- Apatheia: Not apathy, but inner freedom from compulsions — akin to virāga (dispassion).

- Hesychia: Interior stillness — the quiet of samādhi.

- Penthos: Holy sorrow — a tender form of nibbidā (disenchantment) that leads to purification.

Thus, Christian monastic psychology is deeply therapeutic — an applied technology of the soul aimed at curing the root of suffering.

8.6 Preservation Through the Dark Ages

When the Western Roman Empire fell, it was the monasteries that preserved classical knowledge, sacred texts, and contemplative practice.

- Scriptoria produced copies of the Bible, classical works, and patristic writings.

- Monasteries became safe havens — islands of learning and prayer in a sea of chaos.

This historical role strikingly resembles the vihāras of ancient India and Sri Lanka, which served as sanctuaries for learning during times of political turbulence.

8.7 The Shift to Scholasticism

In the High Middle Ages, a shift occurred: Christian intellectual life became more scholastic, focused on systematic theology, debate, and Aristotelian logic.

While this was a great flowering of thought, it sometimes eclipsed the experiential and therapeutic dimension of the faith.

Monastic contemplation became less central, and salvation was increasingly presented in juridical terms (debt, payment, satisfaction).

Nevertheless, the mystical stream never vanished — it remained alive in monastic enclaves, in the writings of mystics like Meister Eckhart, and later in the Carmelites and hesychast tradition of the Eastern Church.

8.8 The Reformation and the Crisis of Monasticism

The Protestant Reformation (16th c.) rejected monastic vows, emphasizing personal faith and the priesthood of all believers.

While this democratized access to the Scriptures, it also led to the dismantling of contemplative institutions in much of Europe.

Without monasteries, the therapeutic dimension of Christianity became harder to access — though it re-emerged in Protestant pietism, Quaker silence, and modern contemplative renewals.

8.9 Modern Psychology as Secularized Soul-Healing

The very word therapy comes from the Greek therapeia — the same root as Therapeutae.

- Originally, it meant “service” or “healing.”

- Over time, it came to refer specifically to the care of the soul.

Modern psychotherapy, though often secular, still carries this original mission:

- To bring what is unconscious into the light (Freud’s talking cure).

- To confront distortions and false beliefs (cognitive therapy).

- To restore wholeness and meaning (Jungian analysis, logotherapy).

Though stripped of explicit transcendence, these approaches still echo the ancient project of soul-healing — leading the fragmented self toward integration.

8.10 The Missing Dimension: The Deathless

What modern therapy often lacks, however, is the ultimate horizon — the goal of complete liberation.

- Psychology seeks mental health, not liberation from saṃsāra.

- Its horizon is adjustment, not transcendence.

Buddhism and the contemplative Christian tradition offer something more: the deathless refuge (Nibbāna, Kingdom of Heaven) where the purified citta abides beyond the reach of aging and death.

Without this, therapy risks becoming maintenance rather than transformation — keeping the patient functional within the same world, rather than guiding them to a place beyond the world.

8.11 Toward a Reunited Vision

The challenge of our time is to recover the therapeutic and contemplative heart of the spiritual path: