A Meditative Journey Into the True Meaning of the Buddha’s Path

Why the Middle Way Is Still Misunderstood

For centuries, the Buddha’s Middle Way has been flattened into an ethic of moderation:

“Don’t eat too much, don’t starve. Don’t sleep too much, don’t stay awake. Don’t go to extremes.”

And while moderation has value, the Middle Way is infinitely deeper than that.

The Middle Way is not about balancing your lifestyle but about transforming your vision.

It is about refusing the delusion that the world can be embraced for happiness or destroyed for freedom.

It is about seeing the world clearly, purifying the citta (mind-heart), and transcending the entire system of craving and becoming.

This is why the Middle Way is still misunderstood.

It is not merely a psychological middle between pleasure and pain — it is the cosmic middle, the middle exit between two great traps: indulgence in the world and annihilation of the self.

The Two Extremes — Not What You Think

When the Buddha first taught the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, he began with a warning:

“Ete kho, bhikkhave, dve antā pabbajitena na sevitabbā…”

“These two extremes, bhikkhus, are not to be practiced by one who has gone forth…” — SN 56.11

The first extreme is easy to understand:

- Kāmasukhallikānuyoga — indulgence in sense pleasures.

This keeps beings fettered to the lower worlds, constantly seeking satisfaction in food, sex, comfort, entertainment, and distraction — and finding only temporary relief followed by the same hunger again. This is the extreme that people understand today without ambiguity. Let’s review it:

Lowest Extreme or Trap (Antā) – Kāma Sukha Anuyoga: Self Indulgence in Sensual Pleasure. Love of the sensual world, clinging to its pleasures and sex, which perpetuates becoming, aging, and death in lower realms.

Characteristics:

- Driven by Craving (Taṇhā): This craving is insatiable; satisfying one desire often just leads to the emergence of another, perpetuating a cycle of wanting.

- Impermanence of Pleasure (Anicca): All sensual pleasures are inherently impermanent (anicca). They arise and pass away. Clinging to them inevitably leads to disappointment and suffering when they fade or are lost. The “happiness” they provide is fleeting and conditional.

- Unsatisfactoriness (Dukkha): Because sensual pleasures are impermanent and cannot provide lasting satisfaction, clinging to them leads to dukkha (suffering, unsatisfactoriness). The constant pursuit, the anxiety of loss, the boredom when a pleasure subsides, and the frustration when it’s unattainable—all these are forms of suffering inherent in Kāma Sukha Anuyoga.

- Entanglement and Bondage: This trap keeps an individual entangled in the cycle of samsara (repeated existence) in lower realms. It creates strong attachments and identifies one with the material world and fleeting experiences, preventing the detachment necessary for liberation.

Hindrance to Mental Development:

- Distraction: The pursuit of sensual pleasures is a major distraction from mental cultivation. The mind becomes preoccupied with planning, acquiring, experiencing, and regretting for pleasures, leaving little room for mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom.

- Lack of Insight: Immersing oneself in sensory experience prevents one from seeing the true nature of reality – the human nature and the nature of the world. The mind remains superficial, drawn outward rather than inward.

- Weakening of Resolve: It can weaken one’s resolve and energy for spiritual practice, as comfort and ease become preferred over the effort required for insight.

Ethical Implications: While not inherently “evil,” the unrestrained pursuit of sensual pleasure can often lead to unskillful or unethical actions. For example:

- Exploiting others to gain pleasure.

- Breaking ethical precepts (e.g., stealing, sexual misconduct) due to overwhelming desire.

- Generating greed and attachment that can harm oneself and others.

“Low, vulgar, worldly, ignoble, and unprofitable”: These are the exact words the Buddha used to describe Kāma Sukha Anuyoga.

- Low/Vulgar (hīna): It refers to a base or inferior pursuit, not leading to higher states of being.

- Worldly (gāmma): It keeps one tied to the ordinary, unenlightened ways of the world, away from the transcendental.

- Ignoble (puthujjanika): It’s characteristic of ordinary, unenlightened individuals (puthujjana), not those striving for nobility of mind.

- Unprofitable (anatthasaṃhita): It does not lead to genuine well-being, peace, or liberation; instead, it generates more suffering.

But the second extreme is subtler, and here is where many misunderstand:

- Atta-kilamathānuyoga — often mistranslated as “self-mortification.”

In the common view, this simply means starving or torturing the body.

But the Buddha’s warning is deeper: it includes misdirected tapas and samādhi — spiritual practices that aim at self-erasure, at dissolving individuality into the cosmic Source.

This second extreme is especially dangerous because it appears holy.

The stillness of the formless attainments is so exquisite, so luminous, that it can easily be mistaken for final freedom.

Indeed, the Buddha himself mastered these states under Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta.

He entered the base of infinite consciousness, the base of nothingness, and even the state of neither-perception-nor-non-perception — the very pinnacle of meditative refinement — and saw that they still end.

He saw that what many traditions called “liberation” was only a suspension — a pause before the wheel turns again.

And he saw that complete merger with the Source, while blissful, leads not to freedom but to annihilation — the extinguishing not of craving but of the manussa spark itself.

The Subtle Trap: When Ascent Becomes Annihilation

It is natural to be inspired by the vision of ascension.

Through tapas, through jhāna, through the yogas of India and the alchemies of China, countless seekers have lifted their consciousness into the higher worlds.

This is no small achievement.

Ascension offers profound benefits:

- Purification: The body is disciplined and becomes light, the nāḍīs and meridians are cleared, and the mind grows steady and luminous.

- Longevity: The life-force is conserved and refined; some attain lifespans stretching over centuries or aeons, radiant as devas.

- Elevation of Consciousness: The mind ascends through the jhānas, leaving behind coarse perceptions, discovering the sublime stillness of the rūpa-loka.

- Transcendent Bliss: It may rise beyond form into the arūpa-loka — infinite space, infinite consciousness, nothingness.

From a cosmic perspective, this is the highest perfection available within the universe.

And yet, here lies the subtle danger:

The higher one ascends, the closer one comes to the Source.

In the formless worlds, individuality grows faint, like a candle in a vast night sky.

Union with the Source may be praised by many traditions as the highest attainment — but from the Buddha’s realization, it is dissolution, the golden cage of the arūpa-loka.

One may dwell there for aeons, but when the universe collapses, even these beings are drawn back into the stream or dissolve entirely into the Source.

The Middle as the Gate — Not the Compromise

The Buddha did not reject tapas — he perfected it.

He did not abandon samādhi — he directed it toward the middle exit.

The Middle Way (Majjhimā Paṭipadā) is not a compromise between pleasure and pain.

It is the discovery of the hidden gate, the doorway between the two poles of saṃsāra.

- One extreme: indulgence in sense pleasure — sinking into the lower worlds.

- The other extreme: self-erasure — dissolving into the upper worlds.

- The middle: the hidden threshold that opens not higher but outward, leading beyond the universe entirely.

“Atthi, bhikkhave, ajātaṃ abhūtaṃ akataṃ asaṅkhataṃ…”

“There is, bhikkhus, the unborn, the unbecome, the unmade, the unfabricated…” — Udāna 8.3

This is the Buddha’s discovery: the asaṅkhata, the unconditioned — not another state within the system, but the exit from the system itself.

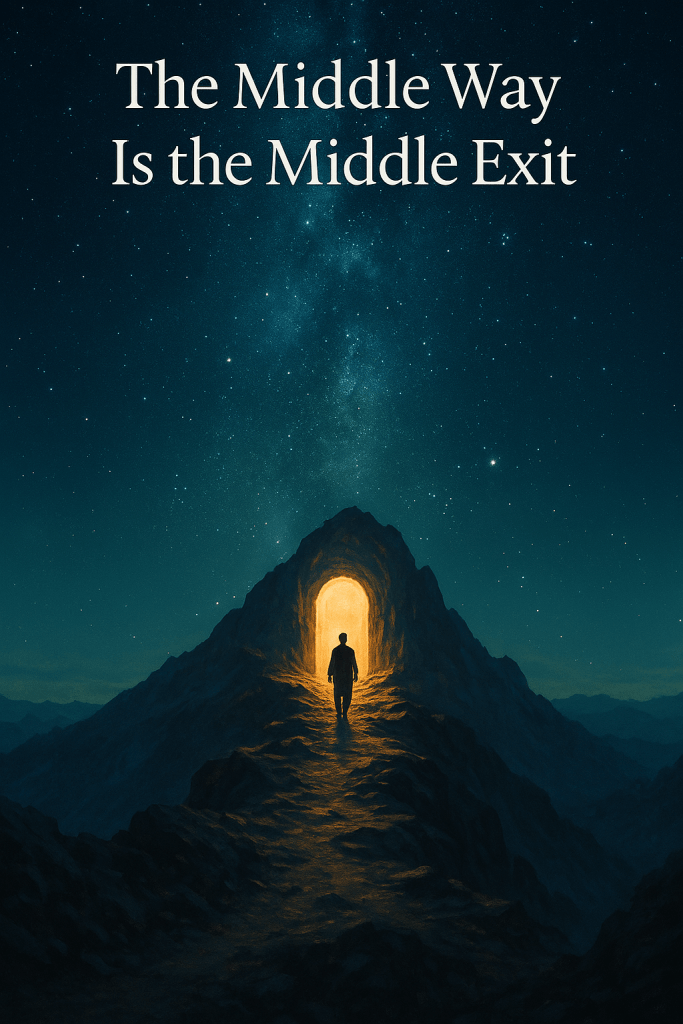

Standing Before the Middle Gate

Imagine standing at the summit of the cosmic mountain.

Behind you lie the valleys of birth and death.

Above you stretches the formless sky, calling you to merge and rest.

The Buddha stood there too.

He looked downward and saw the futility of indulgence.

He looked upward and saw the trap of dissolution.

And then he saw something hidden — a narrow pass between the two, invisible to gods and humans alike.

This is the Middle Gate, the Middle Exit.

Not a balancing act, not a compromise — a doorway out of both.

Not worldly existence, not non-existence — freedom from the whole polarity.

The Call to Walk Through

The Buddha’s voice still echoes:

“Tumaṃhi kiccaṃ ātappaṃ, akkhātāro tathāgatā.”

“You yourselves must make the effort; the Tathāgatas only show the way.” — Dhp 276

The map has been given: sīla, samādhi, paññā — discipline, concentration, wisdom.

Tapas remains the foundation, samādhi the bridge, paññā the compass that points to the hidden pass.

Do not settle for the lower valleys.

Do not dissolve into the upper sky.

Stand here, in the middle, where the gate is —

and when the citta is ready, step through,

into the freedom that lies beyond the highest heaven.

Leave a comment