From Ṛṣis, Siddhas, and Xian to the Buddha’s Path Beyond the Universe

Beyond the Highest Heaven: Why Ascension Is Not the End

Every spiritual tradition tells a story of ascent.

The Indian ṛṣis left their villages and saw the eternal law (ṛta).

The Siddhas transformed their bodies until they glowed with immortal vitality.

The Daoist immortals (仙) withdrew into the mountains, refining essence and spirit until they could walk among the clouds.

These stories inspire us because they awaken something ancient in the heart — a memory that human life was never meant to be limited to birth, aging, and death.

They whisper: you too can rise, you too can transcend.

And indeed, ascension is a noble path.

It purifies the body, clarifies the mind, and brings us into harmony with the cosmic order.

Through tapas — the discipline of body and mind — and samādhi — the stilling of the citta — we may even glimpse the higher worlds, the radiant dimensions of the rūpa-loka, the vast serenity of the formless spheres.

But here lies the subtle trap: these higher attainments are not the final freedom.

They are the golden cage of the cosmos — exquisite, luminous, but still within the system.

Even the formless worlds eventually dissolve back into the Source, and the individuality we worked so hard to purify is surrendered back to the cosmic order.

Gautama Buddha saw this with piercing clarity.

He mastered the highest meditative attainments, entered the state of neither-perception-nor-non-perception — and saw that it still ends.

He realized that there is a middle gate, a hidden exit between the two extremes of indulgence and self-annihilation.

This is the Majjhimā Paṭipadā, the Middle Way — not a compromise between pleasure and pain, but a path out of the whole polarity.

It is the middle exit that opens from the summit of the rūpa-loka, leading beyond the cosmos itself into Nibbāna-dhātu, the deathless.

The invitation of the Buddha is therefore radical:

Do not settle for heaven.

Do not dissolve into the Source.

Purify the citta, gather your strength, and step through the gate that lies beyond the highest heavens.

The true destiny of the human being — the manussa spark — is not to merely rise but to exit.

The path is open.

The map is clear: sīla, samādhi, paññā — discipline, stillness, wisdom.

The rest is up to us.

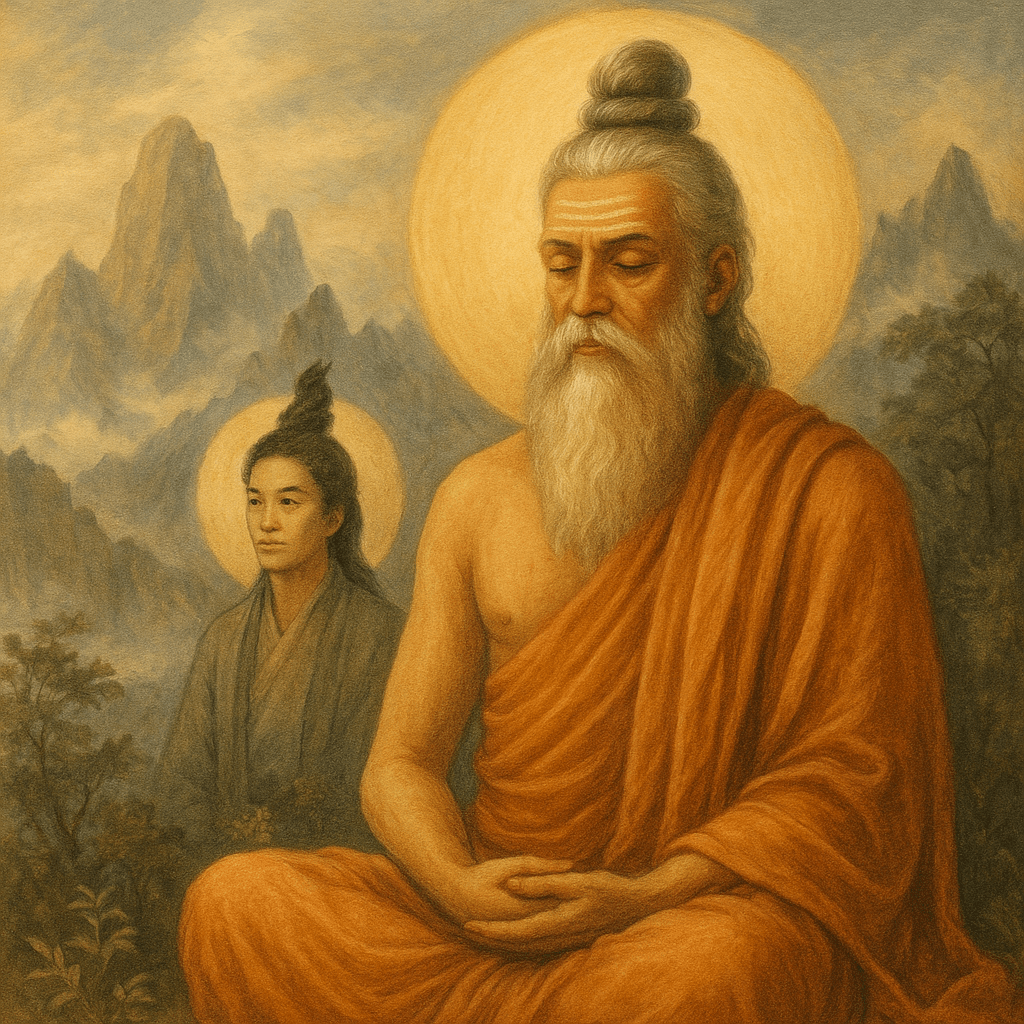

1. Opening Meditation: The Archetype of the Divine Human

“Within every human lies the memory of flight — the knowing that we were not born to die, but to rise.”

Before words, before doctrines, before the first question of philosophy — there was a feeling.

A feeling that life could not end with decay.

A feeling that there must be more than the cycle of birth, aging, sickness, and death.

Imagine standing at the edge of a forest at dawn.

Mist clings to the trees.

The air is cold, alive with birdsong.

Somewhere in the distance, a solitary figure sits cross-legged, unmoving, as if carved from stone.

The first rays of sunlight fall upon their shoulders, outlining them in gold.

You sense in that moment that this being is not merely human — or perhaps more human than any you have ever seen.

Across cultures and ages, such figures have been revered — the sages of India, the immortals of China, the saints and seers of every land.

They are remembered not as mere mortals, but as those who pierced through the veil of ordinary existence, who found a way to rise above the chains of the world.

The Universal Longing to Transcend

Every civilization has felt this longing.

In India, it gave rise to the forest renunciants — ṛṣis who left their homes to sit in silence until they could hear the song of the cosmos.

In China, it gave rise to the Taoist hermits — who withdrew into mountains to refine their breath, their body, and their spirit until they could ride away on a white crane.

In the deserts of the Near East, prophets fasted until visions broke through the horizon of the mind.

This longing is not escapism.

It is the most human of instincts: the intuition that life is meant to move toward completion — that we are called to ascend from the half-light of ignorance into the full light of knowing.

The “Divine Human” Archetype

The idea of the divine human — a being who becomes radiant, who gains mastery over body and mind, who can live for centuries and move between worlds — is not merely mythological.

It is an archetype, a memory of what is possible.

The Indian ṛṣis, the perfected siddhas, the Chinese xian — these are not simply cultural curiosities but living symbols of humanity’s potential.

Their lives tell us that aging and death are not absolute masters, that consciousness can be trained until it becomes vast and measureless, that matter itself can be refined into something incorruptible.

They are signs that point to something beyond the human condition — and they stand as invitations: come and see, come and walk this path, come and remember what you truly are.

An Invitation to Walk Slowly

This essay is not a quick argument or a lecture.

It is meant to be read like a pilgrimage, a slow ascent up a sacred mountain.

Each section is a station along the way — a place to stop, breathe, and take in the view.

We will meet the ṛṣis and siddhas of India, the immortals of China, the practices of tapas and samādhi that purify and elevate the being.

We will look at the shining heights of the cosmos — and we will also face the subtle danger that waits at its summit.

And finally, we will turn to Gautama Buddha, who stood at that summit, saw both the valleys below and the skies above, and discovered something hidden — the Middle Exit, the gate that leads not upward or downward, but out.

For now, pause.

Imagine again the figure in the forest at dawn.

Their stillness is not passive — it is the stillness of power, of readiness.

They are waiting for the first light, the first sound of truth.

This is where we begin.

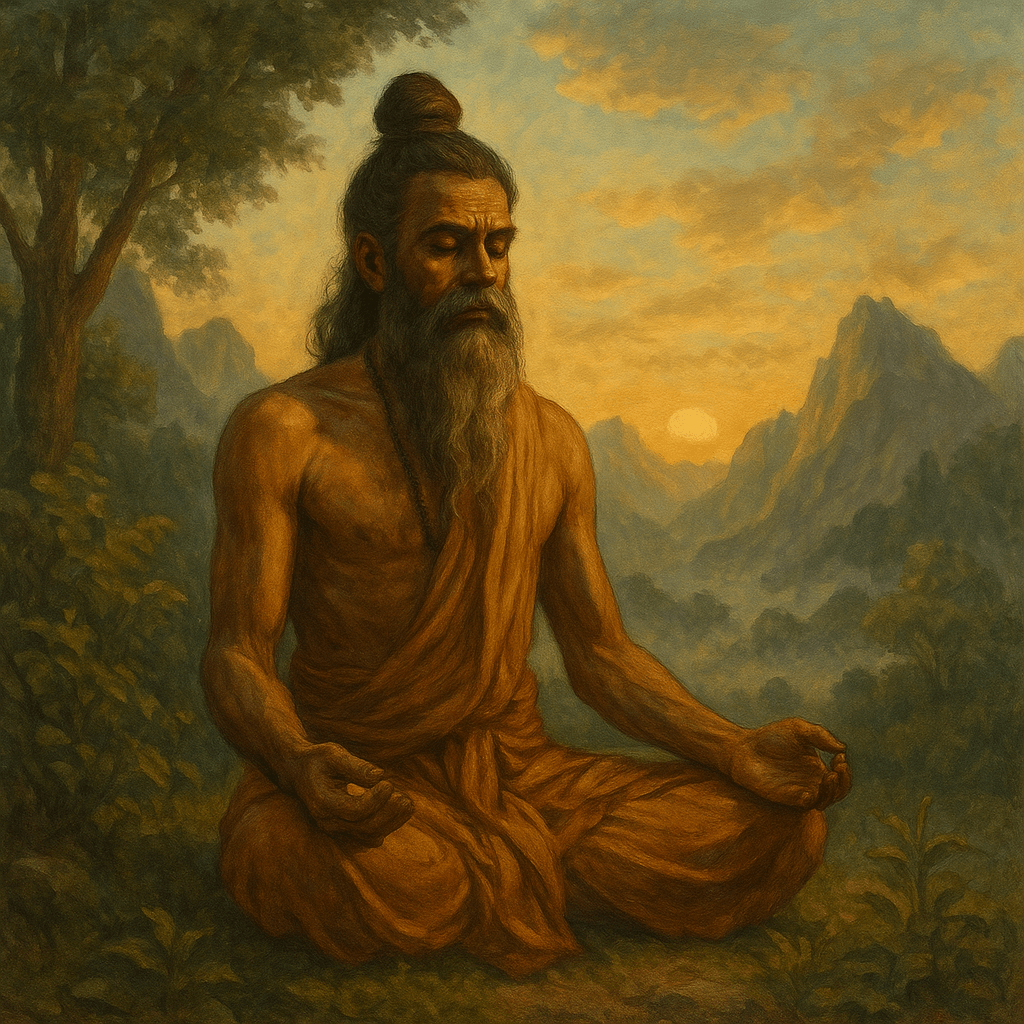

2. India’s Ancient Seers: Ṛṣis (ऋषि)

Long before the Buddha walked the forests of India, before the rise of cities and kingdoms, there were the Ṛṣis.

Their presence is woven into the oldest hymns of the Ṛg Veda — not as mere historical figures but as archetypal seers, conduits through which cosmic truth flowed into human speech.

The World of the Ṛṣis

Picture the India of four thousand years ago.

Dense forests stretch across the land, broken only by clearings where fires burn beneath the stars.

There are no temples yet, no stone images.

Only the open sky, the flickering of the sacred fire, and the voice of the chant.

Here, in forest hermitages (āśramas), the Ṛṣis live.

Their lives are simple: collecting firewood, tending the sacred flame, practicing tapas.

They rise before dawn to recite the mantras, aligning themselves with the cosmic order.

Their entire existence is one of listening — not just with the ears, but with the whole being.

The word Ṛṣi comes from the Sanskrit root √ṛṣ, meaning “to see.”

A Ṛṣi is not simply a poet but a seer, one who perceives the invisible law — ṛta — that sustains the universe.

They are described as mantra-draṣṭāraḥ — “seers of the mantras.”

The hymns they composed were not inventions of the human mind, but revelations, śruti — “that which was heard.”

Guardians of Cosmic Order

The Ṛṣis were custodians of ṛta — the cosmic order that keeps the sun rising, the seasons turning, the worlds in harmony.

To live in accordance with ṛta was to live truthfully; to violate it was to invite chaos.

Thus, their work was not merely spiritual but cosmic: by performing the proper sacrifices, chanting the mantras, and living in purity, they upheld the very structure of existence.

In this way, they were not only seekers but stewards of the universe.

Through them, the line between human and divine blurred: they were addressed in hymns as “foremost among men,” yet their lifespan and knowledge were said to span ages.

The Pāli Canon remembers them with reverence:

“Ye te isayo pubbakā, manussānaṃ seṭṭhā…”

“Those ancient seers, the foremost among men…” — AN 4.73

These were not ordinary mortals but those who had touched a dimension beyond birth and death.

Longevity and Spiritual Immortality

The Ṛṣis are often described as chiranjeevi — “long-lived ones,” living not for decades but for yugas.

Some, like Vyāsa, are said to appear again and again in every age, re-compiling the Vedas, guiding humanity across millennia.

Others, like Mārkaṇḍeya, are said to have witnessed entire cosmic dissolutions and re-creations, standing untouched in the great flood while the universe itself was remade.

Such images are not meant merely as mythic exaggeration.

They speak to a profound truth: that the human mind, when purified, is capable of touching something deathless, something that stands outside the turning of the wheel.

The Ṛṣi’s Practice

The Ṛṣis did not merely think about truth — they became it.

Their lives were an unbroken discipline of tapas:

- Fasting: To purify the body and draw the senses inward.

- Silence: To listen for the subtle currents of thought and sound.

- Meditation: To steady the mind until it became like a polished mirror, reflecting the eternal.

- Sacrifice: Not just outward offerings, but the inward offering of ego and desire.

Through these disciplines, they entered states of heightened vision.

They saw devas, conversed with cosmic powers, and perceived the great cycles of creation and dissolution.

Their hymns do not merely praise the gods — they describe direct communion with them.

The Ṛṣi as Archetype of Ascent

In the Ṛṣis, we see the first great archetype of the divine human:

- A being who purifies body and mind until they become transparent to cosmic truth.

- A being who can see through the three worlds and speak with the voice of the eternal.

- A being who stands at the threshold of mortality and points beyond.

To contemplate the Ṛṣi is to feel the first stirrings of the ascent — the sense that life is not a closed circle but a rising spiral, that there is a higher law to be seen, and that it is worth shaping one’s entire existence to behold it.

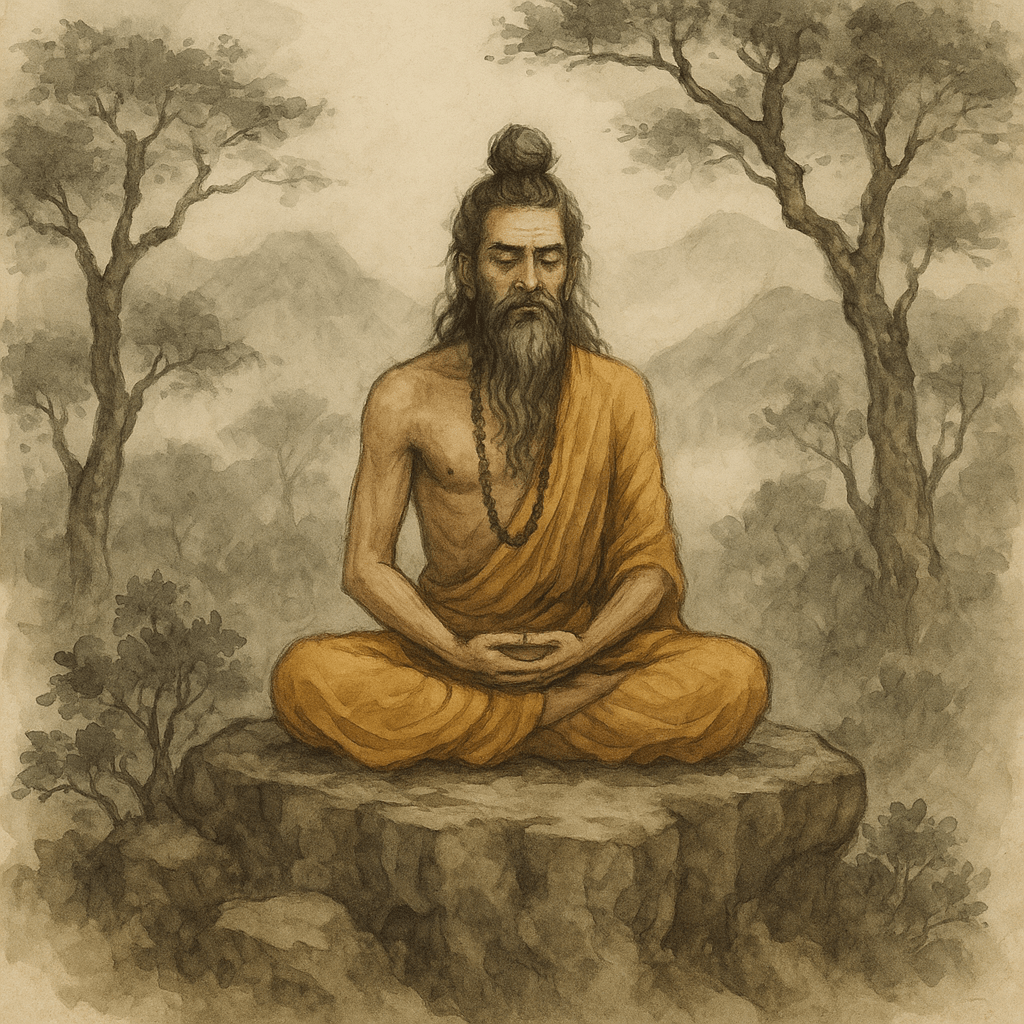

3. The Siddhas: Masters of Transformation

If the Ṛṣis were the seers of truth, the Siddhas were the technicians of transformation.

Where the Ṛṣis heard and proclaimed the hymns of cosmic order, the Siddhas turned inward and began to experiment with the very mechanism of body, mind, and matter.

The Sanskrit word Siddha comes from √sidh, meaning “to accomplish, to perfect.”

A Siddha is therefore not simply a saint or sage but an accomplished one, one who has brought a spiritual process to completion.

Their accomplishment is not theoretical but embodied — written into the very cells of their being.

The World of the Siddhas

Imagine the Indian subcontinent many centuries after the age of the Ṛṣis.

The Vedic sacrifices are still performed, but new paths are opening: the Upaniṣads are being composed, and forest yogis are seeking liberation through renunciation, meditation, and direct inner experience.

It is a time of ferment, of experimentation.

In this period emerge the Siddhas — yogis, alchemists, visionaries — who devote their lives to remaking the human vessel so that it can withstand and channel the infinite.

They are not content merely to know the truth; they wish to become immortal embodiments of it.

The Quest for Perfection

The Siddhas taught that the human body, far from being an obstacle, is the crucible of transformation.

If it can be purified and refined, it can become a kāya-siddha — a perfected body, luminous and incorruptible.

Their disciplines are intricate and demanding:

- Prāṇāyāma (Breath Mastery): Controlling the flow of prāṇa — the vital energy — through alternate nostril breathing, breath retention, and subtle locks (bandhas).

- Mudrās: Gestures and seals that redirect energy flows, closing off the senses and turning the current of vitality inward.

- Rasāyana and Kāya Kalpa: Alchemical rejuvenation — using herbs, minerals, and inner heat to dissolve impurities and rebuild the body from within.

- Mantra and Laya Yoga: Repetition of sacred syllables until the vibration dissolves the mind into pure awareness.

The Siddhas were not afraid of experimentation.

Some worked with mercury and gold, seeking the legendary elixir that could transmute base metal into noble metal — and the mortal body into an immortal one.

Others sought to ignite the latent serpent power (kuṇḍalinī) at the base of the spine, to raise it through the central channel and awaken every energy center until consciousness became cosmic.

Signs of Attainment

As the Siddhas progressed, extraordinary abilities — siddhis — arose as natural byproducts:

- Aṇimā: The ability to become minute as an atom.

- Mahimā: The ability to expand to cosmic size.

- Laghimā: The ability to become weightless, to levitate.

- Prāpti: The ability to travel anywhere, even across worlds, in an instant.

- Iṣitva and Vaśitva: The power to command the elements and the minds of others.

These powers are not mere fantasy.

The early Buddhist texts also describe them.

The Samaññaphala Sutta (DN 2) lists the fruits of spiritual practice, culminating in the mastery of the mind:

“So abhiññāya cittaṃ pariyādāya…”

“Having comprehended and mastered the mind…”

The text continues with a vivid description of the iddhi-vidhā, the supernormal powers:

“Having been one, he becomes many; having been many, he becomes one.

He appears and vanishes.

He goes unhindered through walls, ramparts, and mountains as though through space.

He dives in and out of the earth as though it were water.

He walks on water without sinking as though it were earth.

Seated cross-legged, he travels through the sky like a winged bird.

With his hand he touches and strokes the moon and sun, so powerful and mighty.

He masters the body as far as the Brahmā world.”

Such descriptions are not meant as spectacle but as confirmation: when the citta is purified and steady, the laws that bind ordinary matter no longer hold.

The Siddha as Archetype of Mastery

If the Ṛṣi embodies vision, the Siddha embodies power.

He demonstrates that the human being can, through discipline and knowledge, transcend the limits of flesh and live as an immortal among mortals.

His very body becomes a signpost, pointing beyond decay and death.

But there is also a shadow here.

For the Siddha’s path, with its emphasis on transformation and power, can become intoxicating.

The pursuit of siddhis can easily become an end in itself, and the quest for physical immortality can keep one circling within the cosmos — radiant, yes, but still bound.

The Siddhas are therefore both an inspiration and a warning: they remind us that the body is the gateway, not the final destination; that power must serve wisdom; that ascension must ultimately open into liberation.

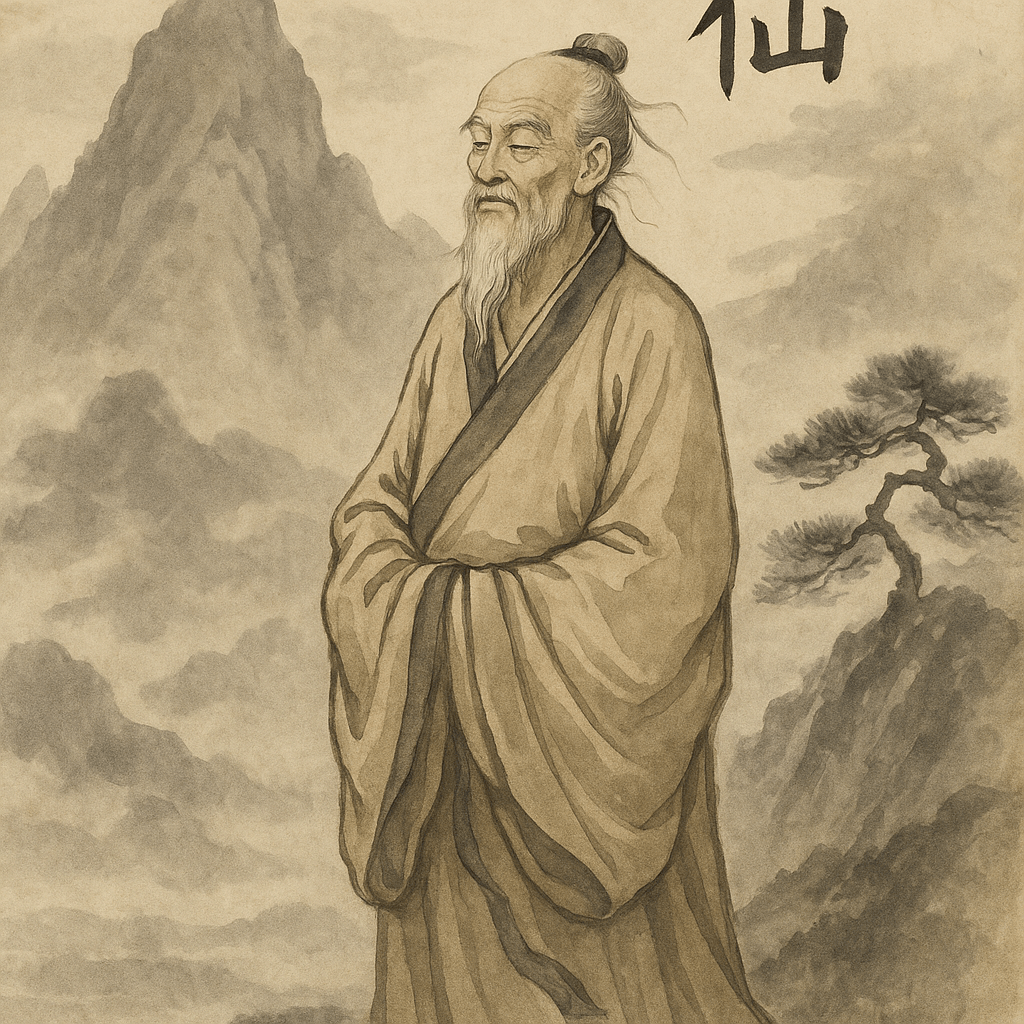

4. China’s Immortals: Xian (仙)

Far to the northeast of India, across mountains and deserts, another current of wisdom was flowing.

In the ancient land of China, seekers also turned away from the bustle of cities and withdrew into the mountains.

There, amid mist-shrouded peaks and whispering pines, they sought not merely long life but transcendence — to become xiān (仙): immortals, transcendent humans.

The Character 仙: Human on the Mountain

The character 仙 is composed of two parts:

- 人 (rén): “Human.”

- 山 (shān): “Mountain.”

Together they suggest “the human in the mountains,” or “the human who has become like the mountain.”

The image is perfect: a person who has risen above the dust of the world, who dwells in stillness, who abides close to Heaven.

The World of the Daoist Immortal

Picture the landscape:

A solitary hut perched on a high peak.

Clouds drift below, cranes circle overhead.

A waterfall cascades into a deep pool, filling the air with a steady roar.

Inside the hut, an old man sits, his hair white, his eyes bright as stars.

Though centuries have passed, he has not aged.

This is the image of the Daoist immortal — serene, powerful, beyond the reach of ordinary time.

He has transformed his body into an incorruptible vessel, his spirit into pure light.

He may remain in the mountains, silently guiding seekers who find him, or he may roam freely between Heaven and Earth, manifesting wherever needed.

The Path of Inner Transformation

Daoist practice distinguishes between external alchemy (waidan) and internal alchemy (neidan).

- External Alchemy: Early Daoists experimented with elixirs of immortality, made from cinnabar, gold, and rare herbs. Many of these formulas were toxic, and some seekers died in their quest.

- Internal Alchemy: Over time, the focus turned inward. The true elixir was recognized as something to be refined within the human body.

Internal alchemy is a science of transformation as intricate as anything in India:

- Refining Essence (Jing): Conserving sexual energy, living in purity, strengthening the body.

- Transmuting Energy (Qi): Circulating vital breath through the meridians, especially the Microcosmic Orbit (small heavenly circuit).

- Transforming Spirit (Shen): Quieting the mind until it becomes luminous, merging the individual spirit with the universal.

- Returning to Emptiness (Xu): Dissolving even the subtle sense of separateness until one abides in the Dao.

This process is often symbolized as the forging of an “immortal embryo” — a subtle, radiant body within the mortal body, which, when fully formed, can survive the death of the physical shell and ascend to the realms of the immortals.

Immortal Legends

Chinese tradition remembers many great immortals.

The Eight Immortals (Bāxiān) are among the most beloved:

- Lü Dongbin: A scholar who was tested by dreams of wealth and pleasure, then renounced the world and attained transcendence.

- He Xiangu: A woman who cultivated purity and was said to fly through the air, scattering blossoms of blessing wherever she went.

- Li Tieguai: A crippled beggar who traveled between Heaven and Earth, carrying a gourd full of magical medicines.

These stories, like those of the Siddhas, are not merely folktales.

They are maps of transformation, showing that the path is open to anyone — scholar, woman, beggar — who is willing to undertake the discipline of refinement.

Xian as Archetype of Harmony

If the Ṛṣis embody vision and the Siddhas embody power, the Daoist immortals embody harmony — living in effortless accord with the Dao, the Way of Heaven.

They are portrayed not as warriors or ascetics but as sages who laugh easily, drink wine, play music, and wander freely.

Their transcendence is gentle, natural, like a pine tree that has stood for a thousand years, slowly becoming one with the mountain it grows upon.

A Parallel Path of Ascent

In the Xian tradition, as in the Siddha tradition, the body is not rejected but transformed.

Death is not inevitable but a challenge to be overcome.

Consciousness is not trapped but can roam beyond the boundaries of space and time.

Together, these archetypes — Ṛṣi, Siddha, Xian — form a great chorus across Asia, all pointing to the same truth:

that the human being is meant for more than mere survival, that within this fragile body lies a spark capable of becoming deathless.

5. Shared Map of Ascent

Standing back from the Ṛṣis, the Siddhas, and the Daoist Immortals, we can see a single pattern emerging — a shared human intuition that life is not meant to remain bound by death.

These traditions arose in different lands, spoke different languages, and used different symbols, but they trace the same essential map:

- Departure: A turning away from the ordinary world — leaving village, palace, or city to seek a higher life.

- Purification: Discipline of body, speech, and mind — fasting, silence, solitude, ethical conduct — to clear the channels of perception.

- Stabilization: Deep meditation and energy practices that gather and refine life-force, allowing consciousness to become still and powerful.

- Transformation: The emergence of a new kind of human — radiant, long-lived, wise, capable of perceiving and traveling between worlds.

- Communion: A life lived in harmony with the cosmic order, conversing with devas, immortals, and the laws of Heaven.

Across India and China, and indeed across the ancient world, this path was seen not as fantasy but as the highest calling.

It was the fulfillment of the human destiny: to become more than mortal, to stand at the meeting point of Heaven and Earth, to live as a bridge between the worlds.

A Single Archetype, Many Names

The Ṛṣi, the Siddha, the Xian — each represents a facet of the divine human archetype:

- Ṛṣi (ऋषि): The seer, who beholds the eternal law (ṛta) and gives voice to cosmic truth.

- Siddha (सिद्ध): The perfected one, who refines body and mind until they become luminous, immortal vessels.

- Xian (仙): The transcendent one, who lives in harmony with the Dao, moving freely between the realms of spirit and matter.

Together they tell a single story: that the human being is not merely a creature of flesh but a potential immortal, a spark of higher order temporarily clothed in matter.

The Manussa Spark

Here your teaching shines with particular clarity.

In the Buddhist view, the human realm — manussa-loka — is uniquely precious because it is the place of choice.

It is here that the manussa spark — the true, eternal seed of consciousness — has the chance to remember itself and turn toward liberation.

The Ṛṣis, Siddhas, and Xian represent a memory of what manussa can be when that spark is awakened:

- No longer bound by instinct or mere survival.

- Capable of remembering its origin beyond the cosmos.

- Capable of gathering its energies, purifying its defilements, and rising to meet its true destiny.

The First Ascent

This is the first ascent — the rising from mere creaturehood into divinity.

It is a journey up the mountain of existence, from the valleys of the kāma-loka to the shining peaks of the rūpa-loka and beyond.

It is a heroic undertaking, and it must be honored: without this ascent, the citta remains too heavy, too clouded, too distracted even to glimpse the possibility of freedom.

And yet, as we will see, this is not the end of the story.

For at the summit of this great mountain there lies a paradox — a subtle danger that even the highest ascetics and the most radiant immortals must face.

This is the moment when the path of ascension becomes the path of decision:

whether to merge with the Source and dissolve, or to take the hidden exit that leads beyond the whole cosmic structure.

6. Tapas: The Turning of the Citta

“Tapas is not torment but alignment — the fire that realigns life with its deepest center.”

At the foundation of every path of ascent lies tapas.

The word is ancient, appearing already in the Vedas, and often translated as “heat,” but its meaning is much deeper.

Tapas is not mere burning; it is the inner fire of alignment — the discipline that reconnects life with its deepest center, the attā, the manussa soul-template.

Tapas is the great reset, the act of turning the citta from its outward dispersion toward its original orientation: freedom.

The Law of Energy Reversal

In ordinary life, energy is constantly spent outward: seeking food, pleasure, distraction, entertainment.

The senses are always reaching, grasping, pulling the citta into the world.

Tapas interrupts this outward flow.

When food intake is reduced, when the tongue is silenced, when the body is stilled, energy begins to gather inward.

The citta no longer chases after stimulation — it grows bright, steady, resilient.

This is not punishment.

It is lawful transformation:

- Purification: Old defilements lose their fuel and rise to the surface, where they can be seen and abandoned.

- Stabilization: The citta ceases to scatter and becomes capable of deep samādhi.

- Repatterning: New wholesome patterns are imprinted; the manussa spark reorients toward exit.

Tapas re-centers the entire being on the axis of truth, restoring its original design.

The Disciplines of Tapas

Across cultures, tapas takes many forms — each designed to purify the body, clarify the mind, and awaken the will:

- Fasting: From partial fasts to complete abstinence on holy days — clearing the system, humbling the appetites, sharpening awareness.

- Mauna (Silence): Withdrawing from speech to conserve energy, quiet the mind, and break the compulsion to respond to every impulse.

- Solitude: Dwelling apart from the crowd, away from distractions, so the citta can hear its own subtle voice.

- Elemental Exposure: Enduring heat, cold, rain, or wind — not to punish the body but to discover that it is not the master.

- Celibacy (Brahmacariya): Conserving vital energy (ojas), redirecting it upward into spiritual practice.

- Vigil: Staying awake to break the habitual patterns of sleep, entering deeper states of concentration.

Each of these disciplines is like a chisel striking away at the stone that surrounds the inner being, revealing the luminous form within.

Tapas in the Life of the Buddha

The fourth sight that Gautama saw before leaving the palace was precisely the image of this path: the wandering renunciate — lean, serene, free.

It was this vision that stirred him to seek the deathless.

For six years he practiced tapas in its most extreme forms: fasting until he was reduced to skin and bones, holding his breath until his head rang like a drum, sitting unmoving through heat and cold.

These were not errors but preparations.

Through tapas he purified the body and senses, gathered energy inward, and steadied the citta.

Only when this inner axis was fully aligned did he see that starvation was no longer necessary — that the work was now to bring the citta to perfect equipoise in samādhi and direct it toward awakening.

Tapas as Universal Law

The power of tapas is not confined to India.

It is a universal law recognized by every culture that has sought higher vision:

- Shamans fasted and kept vigils to enter the spirit world.

- Prophets of Israel withdrew into the desert to hear the word of God.

- Jesus fasted forty days before beginning his ministry.

- Daoist hermits practiced bigu — grain avoidance — to refine their bodies and open subtle perception.

All followed the same law: by restructuring the body, they restructured the mind.

When the body is purified and its cravings subdued, the citta becomes steady and transparent.

It can see through the illusions of the world and remember its true purpose.

The Turning Point

At its deepest level, tapas is the turning of the citta — from outward wandering to inward rest.

When the dependencies of the body loosen, when sense-desires no longer dictate action, the citta becomes a radiant, still pool.

This is the threshold where the mind becomes capable of samādhi — the deep stillness that is not merely quiet but powerful, the gateway to higher realms.

Here the practitioner stands ready to ascend — not as an escape from life but as its fulfillment, as the blossoming of the manussa spark into its full radiance.

7. Samādhi: Doorway to the Higher Worlds

“Samādhi is not escape but awakening — the stillness where the mind becomes vast enough to touch the higher worlds.”

If tapas is the turning of the citta, samādhi is its stilling — the moment when the turning is complete, and the mind no longer trembles under the winds of the world.

The word samādhi comes from sam- (“together”), ā (“toward”), and dhā (“to place”).

It means “to place together,” “to collect,” “to bring into alignment.”

Samādhi is the unification of the mind — the gathering of scattered energies into a single, steady flame.

The Experience of Jhāna

The Buddha spoke of four primary jhānas — deep meditative absorptions — as the stages by which the citta becomes luminous and unshakable.

Each is like a terrace on the mountain of ascent, higher and more refined than the last:

- First Jhāna: Born of seclusion and ethical purity.

- The coarse chatter of the senses subsides.

- The body is suffused with rapture (pīti) and joy (sukha).

- Thought still moves, like ripples on a calm pond.

- Second Jhāna: Born of concentration.

- Thought falls silent; the pond becomes perfectly still.

- Joy deepens, flooding the whole being like a spring filling a deep pool.

- Third Jhāna: Born of equanimity.

- Joy becomes serene, gentle, no longer excited.

- The citta becomes vast, steady, balanced like a mountain.

- Fourth Jhāna: The summit of form meditation.

- Even pleasure and pain fall away.

- The mind becomes pure, clear, utterly still — like a flawless crystal.

Each jhāna is not just a state of mind but a state of being.

In the language of ancient cosmology, these are not merely mental moods — they are dimensions of existence, gateways to the rūpa-loka, the worlds of luminous form.

The Arūpa Samāpatti: The Formless Attainments

Beyond the fourth jhāna lies a subtler series of states — the arūpa samāpatti, the formless attainments.

Here the citta leaves behind even the perception of form and enters the vastness of the formless worlds:

- Ākāsānañcāyatana: The base of infinite space — the sense of being without edges, as if consciousness is as wide as the sky.

- Viññāṇañcāyatana: The base of infinite consciousness — space itself dissolves, leaving only the vast, luminous field of knowing.

- Ākiñcaññāyatana: The base of nothingness — even consciousness seems to vanish, leaving a profound and peaceful void.

- Nevasaññā-nāsaññāyatana: The base of neither-perception-nor-non-perception — a state so subtle it is almost beyond grasp, like a flame so fine it gives no heat.

These states are exalted beyond anything the ordinary mind can imagine.

In them, the citta is no longer bound by the gravitational pull of the senses; it soars free, radiant, immeasurable.

The Arising of Iddhi Powers

When the mind becomes this steady, a natural consequence is the arising of iddhi — psychic powers.

These are not “magical tricks” but the natural abilities of a citta no longer shackled by matter.

The Buddha describes these powers in detail in the Samaññaphala Sutta (DN 2):

“Having been one, he becomes many; having been many, he becomes one.

He appears and vanishes.

He goes unhindered through walls, ramparts, and mountains as though through space.

He dives in and out of the earth as though it were water.

He walks on water without sinking as though it were earth.

Seated cross-legged, he travels through the sky like a winged bird.

With his hand he touches and strokes the moon and sun, so powerful and mighty.

He masters the body as far as the Brahmā world.”

In other words, the Siddhas were not exaggerating — the human mind really can walk on water, fly through the sky, and touch the worlds of the gods when fully liberated from its fetters.

Samādhi as Gateway

Samādhi is thus both culmination and doorway.

It is the culmination of tapas, the flowering of all the discipline and purification that came before.

And it is the doorway to the higher worlds, the means by which the citta rises into the luminous dimensions of the rūpa-loka and beyond.

But as we will see in the next section, this doorway is also a threshold of decision.

For at the top of this ascent, the practitioner faces a choice:

whether to merge with the formless and dissolve, or to find the hidden exit that leads beyond the cosmos entirely.

8. The Subtle Trap: When Ascent Becomes Annihilation

“Even the formless heavens are not the end — they are the most beautiful prison in the cosmos.”

It is natural to be inspired by the vision of ascension.

The human heart longs to rise — to transcend suffering, decay, and the narrow confines of ordinary life.

Through tapas, through jhāna, through the yogas of India and the alchemies of China, countless seekers have lifted their consciousness into the higher worlds.

This is no small achievement.

Ascension offers profound benefits:

- Purification: The body is disciplined and becomes light, the channels of energy (nāḍīs, meridians) are cleared, and the mind becomes steady and luminous.

- Longevity: The life-force is conserved and refined; some attain lifespans stretching over centuries or aeons, radiant as devas.

- Elevation of Consciousness: The mind ascends through the jhānas, leaving behind the coarse perceptions of the sense world. It discovers the sublime stillness of the rūpa-loka, the heavenly planes of form.

- Transcendent Bliss: Eventually, it may rise beyond form altogether into the arūpa-loka — the formless spheres of infinite space, infinite consciousness, nothingness, and beyond.

From a cosmic perspective, this is the highest perfection available within the universe. In these exalted states, there is no coarse suffering, no birth and death in the ordinary sense, no pain of embodiment. A being may abide for kalpas, sustained in sublime equilibrium.

And yet, here lies the great and subtle danger.

Tapas as the Foundation — Not the Error

We must be clear: tapas itself is not the problem.

Far from being “self-torment,” tapas is the ancient and universal foundation of the renunciant life.

The word does not simply mean “heat” or “burning” — it means reconnecting with the attā, the true self, the manussa soul-template.

When ordinary indulgence is interrupted — when food, comfort, and distraction are laid aside — the constant outward expenditure of energy stops. Energy gathers inward. The citta grows steady and bright.

- Purification: Old defilements lose their fuel and rise to the surface where they can be seen and abandoned.

- Stabilization: The mind ceases to scatter and becomes capable of deep samādhi.

- Repatterning: The manussa spark reawakens to its original orientation toward freedom.

Gautama himself practiced tapas to the very edge of death — fasting, holding the breath, dwelling in solitude — not as an error, but as preparation.

Tapas realigns the entire being on its true axis and readies it for the final work.

Where the Danger Lies

The danger comes when tapas and samādhi, instead of being used to liberate the citta, are turned toward its annihilation.

When the purified spark is surrendered to the cosmic Source, individuality is lost.

This is the subtle trap of the higher worlds.

The higher one ascends in the cosmos, the closer one comes to the Source — the great reservoir into which all universes eventually collapse.

In the formless worlds, individuality becomes thread-thin.

The sense of “I” grows faint, like a candle-flame in a vast night sky.

To merge with the Source is, from the perspective of many traditions, the supreme attainment.

Hindu texts speak of mokṣa as union with Brahman; Daoist texts of becoming one with the Tao; even some Mahāyāna schools praise the idea of extinction as final nirvāṇa.

But from the standpoint of Gautama Buddha’s realization, this is not freedom — it is dissolution.

The individuality of the manussa spark, hard-won through aeons, is surrendered back to the cosmic order.

One becomes, quite literally, fuel for the Source — participating in its maintenance of the great system, but no longer as a free agent.

The peace of the arūpa-loka is thus a beautiful golden cage.

One may dwell there for unthinkable spans of time, but when the cosmic cycle turns, even these beings are drawn back into the stream, or they dissolve entirely into the Source.

Buddha’s Diagnosis of the Second Extreme

This is why the Buddha warned against the second great trap — the extreme of atta-kilamathānuyoga.

“Ete kho, bhikkhave, dve antā pabbajitena na sevitabbā…”

“These two extremes, bhikkhus, are not to be practiced by one who has gone forth…” — SN 56.11

He spoke of two extremes (antā):

- Kāmasukhallikānuyoga — indulgence in sense pleasures, which keeps beings fettered to the lower worlds.

- Atta-kilamathānuyoga — not merely crude self-torment, but the misdirection of tapas and samādhi toward the goal of self-erasure. This includes not only harsh mortification but also the subtle attempt to dissolve individuality — whether through pain, trance, or even refined meditative absorption aimed at annihilation.

The second extreme is especially dangerous because it appears holy.

It promises peace — and to a degree, it delivers it.

The stillness of the formless attainments is so exquisite, so luminous, that it can be mistaken for the final freedom.

Indeed, the Buddha himself mastered these attainments under Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta.

He entered the state of neither-perception-nor-non-perception — the pinnacle of meditative refinement — and saw that it still ends.

He saw that what many traditions called “liberation” was in fact only a temporary suspension, a pause before the wheel turns again.

And he saw that complete merger with the Source, while sublime, leads not to freedom but to annihilation — not the extinguishing of defilements but the extinguishing of the manussa spark itself.

This is the cosmic dead end, the second antā.

It is not tapas itself that is rejected, but tapas without wisdom — tapas misdirected into the surrender of individuality.

9. Majjhimā Paṭipadā: The Middle Exit

“The Middle Way is not compromise — it is the hidden pass that leads beyond existence and non-existence.”

The Buddha did not reject tapas — he fulfilled it.

He took the raw power of tapas and samādhi, tempered them with wisdom (paññā), and aimed them at the one goal that neither indulgence nor annihilation can reach: the liberation of citta beyond all worlds.

The Middle as the Gate — Not the Compromise

The Majjhimā Paṭipadā (Middle Way) is not a soft compromise between pleasure and pain.

It is the discovery of the middle gate, the hidden exit between the two great poles of saṃsāra.

- One extreme: Kāmasukhallikānuyoga — indulgence in sense pleasures that pulls beings downward into the six realms of kāma-loka, binding them to craving and rebirth.

- The other extreme: Atta-kilamathānuyoga — misdirected tapas and samādhi that aim at self-erasure, pulling beings upward into arūpa-loka, toward dissolution in the Source.

- The middle: The Buddha stands at the ninth dimension — the summit of rūpa-loka — and points to the gate that opens not higher but outward. This is the Middle Way: the middle exit, neither clinging to the low nor surrendering to the high, but walking free of the whole structure.

“Atthi, bhikkhave, ajātaṃ abhūtaṃ akataṃ asaṅkhataṃ…”

“There is, bhikkhus, the unborn, the unbecome, the unmade, the unfabricated…” — Udāna 8.3

This is the Buddha’s discovery: the asaṅkhata, the unconditioned — not another state within the system, but the door out of the system itself.

Tapas and Samādhi Perfected

Thus, tapas is not abandoned but crowned with wisdom.

Samādhi is not discarded but directed toward release.

Together, they form the wings that lift the citta not only upward but outward — across the threshold of the cosmos into the unconditioned.

The Middle Way is therefore not merely moderation.

It is the middle exit — the secret pass that opens only when craving is extinguished, the citta is purified, and wisdom sees through both the trap of indulgence and the trap of annihilation.

10. Closing Meditation: Standing Before the Middle Gate

“Do not settle for heaven. Do not dissolve into the Source. Step through the gate beyond the highest heavens.”

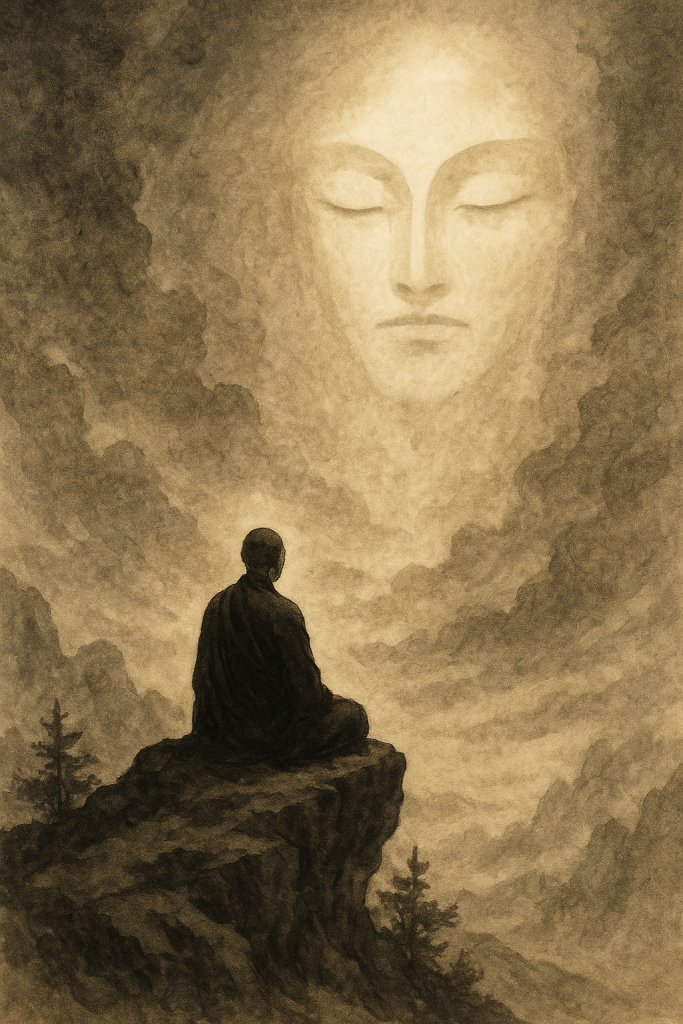

Imagine standing at the summit of the cosmic mountain.

Behind you, the valleys of the human world stretch far below — full of pleasure and pain, life and death.

Above you, the formless sky calls — radiant, silent, promising rest.

This is the place where the Buddha stood.

He looked downward and saw the futility of indulgence.

He looked upward and saw the trap of dissolution.

And then he saw it — a narrow pass between the two, hidden from the view of gods and humans alike.

This is the Middle Gate — the Middle Exit.

Not a compromise between pleasure and pain, but a doorway out of both.

Not a balance between existence and non-existence, but a freedom from the whole polarity.

Here is where the Buddha calls to you:

“Tumaṃhi kiccaṃ ātappaṃ, akkhātāro tathāgatā.”

“You yourselves must make the effort; the Tathāgatas only show the way.” — Dhp 276

The map has been given: sīla, samādhi, paññā — discipline, stillness, wisdom.

Tapas is the foundation, samādhi the bridge, and wisdom the compass that points to this hidden pass.

Do not settle for the lower valleys.

Do not dissolve into the upper sky.

Stand here, at the middle, where the gate is.

And when the citta is ready, walk through —

into the freedom that lies beyond the highest heavens.

Leave a comment