The timeless spirit of renunciation in a new cultural landscape

1. Introduction — The Timeless Spirit of Discipline

To the casual observer, the Vinaya may appear as a code of endless rules. Two hundred and more regulations for monks, even more for nuns, added to precepts for novices and lay followers. A modern reader may wonder: why so many rules? Why such restrictions? Why renounce money, food after noon, or something as simple as singing or dancing?

Yet the spirit of the Vinaya is not about rules for their own sake. It is a spiritual architecture, carefully designed to free the mind from worldly distractions and redirect life energy toward liberation. It shields the practitioner from the pulls of craving, aversion, and ignorance, and points them beyond the cycle of aging and death.

Gautama Buddha himself described the pātimokkha—the fortnightly recitation of the rules of discipline—as the way “toward liberation.” In MN 44 (Cūḷavedalla Sutta), it is defined:

“Katamo ca, bhante, pātimokkho? Yattha sabbapāpassa saṃvarā, sabbapāpassa paṭiviratā, sīlasmiṃ samādānaṃ—ayaṃ vuccati pātimokkho.”

“And what, Venerable Sir, is the [pātimokkha]? Where there is restraint [saṃvarā] from all evil, abstinence [paṭiviratā] from all evil, undertaking of virtue [sīlasmiṃ samādānaṃ]—this is called the pātimokkha.”

Thus, the Vinaya is not arbitrary. It is the lived framework of liberation.

But the Vinaya is not practiced in a vacuum. Its external forms have always been shaped by the social, cultural, and environmental context in which it is lived. In India and Southeast Asia, the Vinaya flourished within societies that respected and supported renunciants. In Canada, a vastly different landscape awaits: cold winters, sparse populations, a non-Buddhist cultural majority, and new realities such as banking, taxes, and transportation.

The challenge is clear: how to preserve the spirit of the Vinaya—its timeless call to disentangle from the world and convert life energy toward liberation—while adapting its forms to Canadian realities.

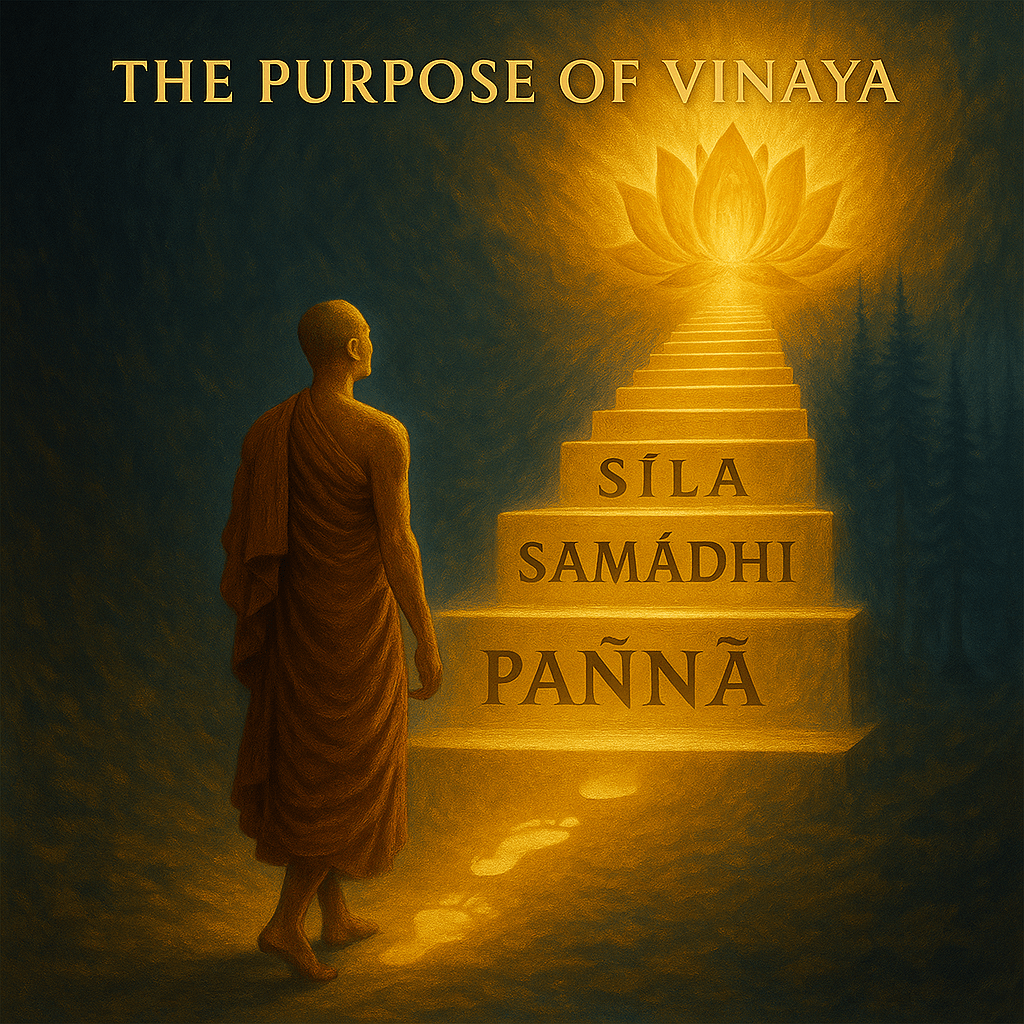

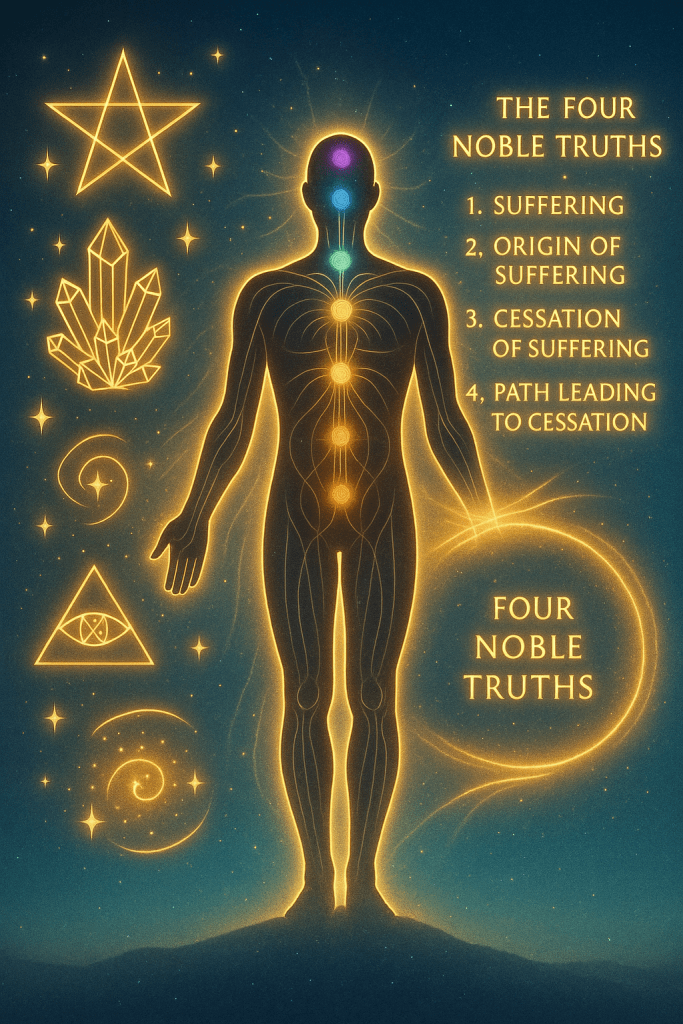

2. The Purpose of Vinaya: Discipline as Path to Liberation

The Vinaya is best understood as a progressive path of training. It is not a sudden leap from worldly life into perfect renunciation, but a gradual redirection of life energy away from sensuality and toward freedom.

Gautama Buddha declared to the first monks in Vinaya Mahāvagga I.11.1:

“Ārādhanā kho pana me vo, bhikkhave, sikkhāpadānaṃ. Sikkhāpadesu sikkhatha, āyatiṃ saṃvarāya.”

“Monks, the training rules [sikkhāpadā] are for your welfare. Train in them for the restraint [saṃvarā] that brings benefit in the future.”

Thus, the Vinaya is never punishment but protection.

The Five Precepts: Foundation for Lay Life

The five precepts (pañca-sīla) are the ground: refraining from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, false speech, and intoxicants. These create harmony and trust, making society trustworthy and minds peaceful. By refraining from the most destructive actions, a layperson begins to stabilize their life energy in wholesome channels.

The Eight Precepts: Stepping Into Renunciation

The eight precepts represent a shift in orientation. Here the lay practitioner, often dressed in white robes, begins to imitate the life of the monastic. Celibacy (brahmacariya) is embraced. Luxuries are abandoned. The evening meal is renounced, leaving only light sustenance such as fruit juice or honey, so that more time and energy may be given to meditation. This is the beginning of brahmacariya, the holy life: converting life energy away from sexuality and indulgence toward stillness and insight.

The Ten Precepts: Novice Training

Novices (sāmaṇera and sāmaṇerī) undertake ten precepts. The additional rule of not handling money is iconic. It symbolizes the break from worldly control and the embrace of full dependence upon the support of others. The novice learns that their body may remain in the world, but their mind is already stepping outside of it.

Full Ordination: The Pātimokkha Discipline

Full ordination (upasampadā) brings the complete discipline: 227 rules for monks, more for nuns. The rules cover all aspects of life, from major to minor, yet their common purpose is clear.

- The gravest rules protect celibacy, ensuring sexual energy is fully sublimated into meditation and insight.

- Other rules prevent entanglement with wealth, politics, and entertainment.

- Still others restrain the senses, minimizing worldly contact so the mind can turn inward.

Even seemingly minor rules—such as restrictions on driving or entertainment—have a spirit: to prevent the dispersal of life energy into worldly pursuits, and to direct it instead toward liberation.

The Vinaya, then, is not merely about morality. It is about conversion of life energy—from sensual indulgence, craving, and distraction, into mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom.

As MN 29 (Mahāsāropama Sutta) reminds us:

“Na kho panetaṃ brahmacariyaṃ vussati ādibhūmiṃ paharitvā, api ca kho uttamena atthena brahmacariyassa vussati: anupādāya āsavehi cittaṃ vimuttaṃ.”

“This holy life [brahmacariya] is not lived for the sake of gain, honor, or fame … but for the supreme goal: the mind [citta] liberated [vimuttaṃ] from the taints through non-clinging [anupādāya].”

3. Ancient Context: Vinaya in India and Southeast Asia

The Vinaya emerged within societies that had long honored renunciants.

- Cultural support: Villagers were accustomed to giving food to holy men. Almsgiving was not only acceptable but meritorious.

- Climate and geography: Mild weather allowed wandering monks to live lightly, with little more than robes and bowls.

- Historical continuity: India’s culture of renunciation predates the Buddha. He did not create it, but gave it structure and clarity through the Vinaya.

This ecosystem was essential. The Vinaya thrived because it harmonized with the rhythms of society. Monastics depended on the laity, and the laity honored the monastics.

In SN 12.65 (Nagara Sutta), he says:

“Purāṇaṃ kho ahaṃ, bhikkhave, maggaṃ anubuddhaṃ, purāṇañca paññāya abhisamayaṃ abhisambuddho.”

“Bhikkhus, I have rediscovered [anubuddhaṃ] the ancient path [purāṇaṃ maggaṃ], the ancient road followed by the Fully Awakened Ones of old.”

In India and Southeast Asia:

- Villagers supported renunciants with alms.

- Climate allowed wandering with minimal possessions.

- A culture of respect made the Vinaya flourish.

4. Canadian Realities: Challenges for Vinaya Practice

In Canada, conditions are strikingly different.

Geographic and Climatic Realities

- Harsh winters make barefoot alms-rounds impossible for much of the year.

- Vast distances and sparse populations prevent monks and nuns from depending entirely on walking to nearby villages.

Cultural Differences

- Canada is not a Buddhist-majority society. Few understand the traditions of alms-giving or daily monastic dependence.

- Renunciation is not embedded in the cultural imagination.

Practical Necessities

- Money and Banking: Necessary for receiving donations, paying utilities, or fulfilling civic obligations.

- Taxes and Legal Duties: Monastics must comply with Canadian law, filing taxes and maintaining legal documents.

- Transportation: Cars are often required simply to acquire food or attend to medical needs.

None of these are indulgences. They are adaptations required for survival in a non-Buddhist cultural and geographic environment. The challenge is to ensure these do not dilute the spirit of renunciation.

5. Preserving the Spirit Amid Adaptation

The key principle for Canadian monastics is not literal replication of Indian or Southeast Asian forms, but faithful preservation of the Vinaya’s spirit.

That spirit can be summarized in one line:

The Vinaya pulls the mind out of the world, restrains the senses, and converts life energy toward liberation.

This means:

- Minimal use of money: Bank accounts only for necessary transactions, never for accumulation or luxury.

- Restricted use of vehicles: Driving only when necessary, never for indulgence or social distraction.

- Continued simplicity: Avoidance of luxuries, adornments, or entanglement in lay affairs.

- Focus on solitude and meditation: Using adaptations only to enable practice, never to excuse distraction.

The essence of adaptation is discernment: distinguishing between what is necessary for survival, and what is unnecessary entanglement.

The Dhammapada (Dhp 360) affirms:

“Cakkhunā saṃvaro sādhu, sādhu sotena saṃvaro, ghānena saṃvaro sādhu, sādhu jivhāya saṃvaro.”

“Restraint [saṃvaro] of the eye is good, restraint of the ear is good, restraint of the nose is good, restraint of the tongue is good.”

6. Canadian Advantages for Vinaya Practice

While the challenges are clear, Canada offers unique and even profound advantages for living the Vinaya.

Solitude and Natural Spaces

Vast forests, lakes, and wilderness areas offer unparalleled opportunities for seclusion. Few places in the world provide such abundant conditions for solitude and meditation.

Religious Freedom

Canadian law protects religious freedom. The government does not interfere in monastic life, leaving renunciants free to practice.

Cultural Openness and Tolerance

Unlike in sectarian societies, Canadians approach Buddhism with curiosity and respect. They are less concerned with sectarian boundaries and more interested in sincerity and authenticity.

Less Sectarianism, More Universality

This openness is crucial. Gautama Buddha himself rediscovered, rather than invented, the path of liberation. Renunciation is an ancient, universal human response to aging and death. In Canada, freed from cultural sectarianism, the Vinaya can be presented not as the property of one tradition but as a universal discipline for the whole race of manussa.

Dialogue with Other Traditions

Canada’s diversity invites dialogue:

- With Christianity’s vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

- With Islam’s fasting and prayer.

- With Indigenous reverence for nature.

- With philosophy’s pursuit of truth.

Each comparison enriches understanding, showing that the renunciant path belongs to humanity as a whole.

Science and Expanding Knowledge

Canada is also a place where science is respected, and this is an advantage for Dhamma. Far from contradicting the path, modern sciences offer complementary insights:

- Neuroscience confirms how meditation reshapes the brain and behavior, validating the transformative power of mindfulness and concentration.

- Quantum physics and cosmology reveal reality as relational and conditioned, resonating with dependent origination and impermanence.

- Archeology uncovers the worlds in which Gautama Buddha lived, reminding us that renunciation was part of a much older human stream.

- Anthropology shows that ascetic lifestyles exist across cultures, proving the path is universal.

- DNA and molecular biology highlight the biological roots of aging, reproduction, and death, echoing Gautama Buddha’s quest to overcome them.

- Linguistics recovers subtle meanings in Pāli texts and reveals cultural connections across civilizations, deepening our appreciation of the universality of the liberation path.

UFO/UAP and Cosmic Disclosures

Even disclosures about extraterrestrial life widen human awareness, reminding us that existence is vast and layered. Gautama Buddha’s cosmology of manussa, devas, and brahmās resonates with this expanded vision. Liberation, therefore, is not limited to humans—it is relevant for all beings.

A New Mentality for Liberation

Thus, Canada offers not only material security and solitude but also intellectual and spiritual space. Here, liberation can be approached with a new mentality: freed from narrow sectarianism, enriched by science and global wisdom, open to cosmic horizons, and grounded in the universal path rediscovered by Gautama Buddha.

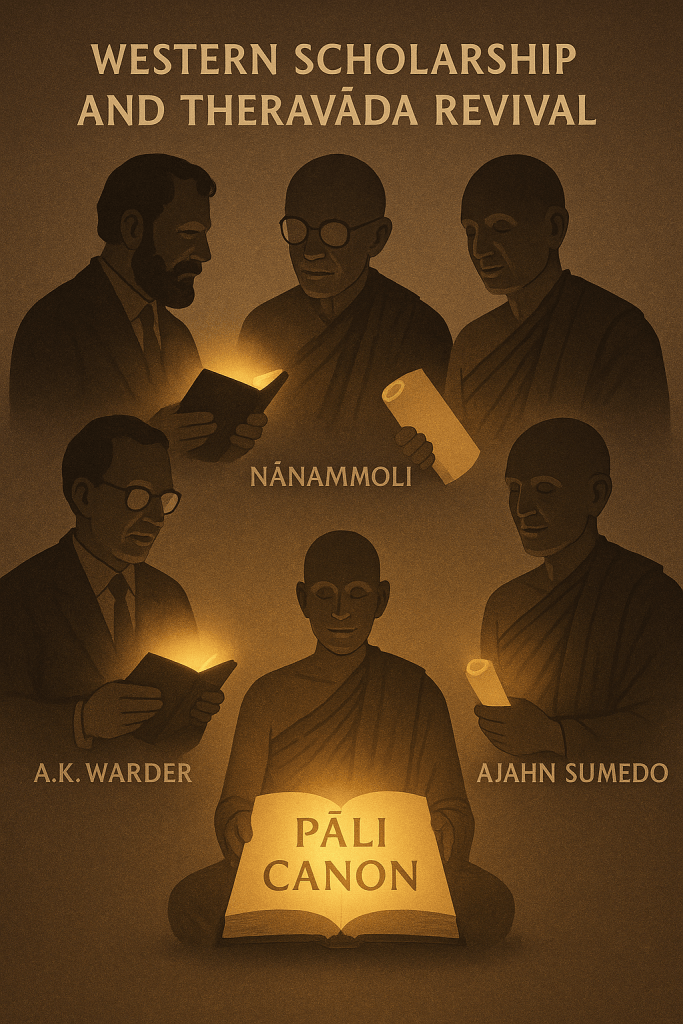

7. Western Scholarship and Theravāda Revival

The modern revival of Theravāda Buddhism has not only depended on Asian monastics but also on the immense contributions of Western scholars, translators, and practitioners. Their painstaking work in systematizing, editing, and translating the Pāli Canon has been one of the most decisive factors in the survival and spread of Theravāda in the modern world.

Pioneers of Pāli Studies

In the late 19th century, the establishment of the Pali Text Society (PTS) by T. W. Rhys Davids (1843–1922) marked a turning point. He, together with Caroline Rhys Davids (1857–1942), began the massive project of publishing Romanized editions of the Pāli Canon. Without this effort, the Canon would have remained locked away in palm-leaf manuscripts scattered across monasteries. Their translations, though imperfect, opened the Dhamma to academic study and public interest across Europe.

Translators and Editors of the Canon

Figures such as I. B. Horner (1896–1981), president of the PTS, translated large portions of the Vinaya Piṭaka and Sutta Piṭaka, bringing critical accuracy and consistency. Maurice Walshe (1911–1998) translated the Dīgha Nikāya, while Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu (1905–1960), an English monk in Sri Lanka, produced seminal translations including The Path of Purification (Visuddhimagga) and The Life of the Buddha. Later, Bhikkhu Bodhi (b. 1944), an American ordained in Sri Lanka, produced authoritative translations of the Majjhima Nikāya, Saṃyutta Nikāya, and Aṅguttara Nikāya, establishing a global standard for study and practice.

Academic Foundations

In Canada, the contribution of A. K. Warder (1924–2013), professor at the University of Toronto, was decisive. His Introduction to Pali trained generations of scholars and practitioners in the language of the Canon. His broader works on Indian Buddhism helped situate Theravāda within the history of world religions, strengthening its credibility and accessibility in academia. In the UK, universities like Oxford and SOAS became centers for Pāli and Buddhist studies, feeding both scholarly and spiritual revivals.

Monastic Bridges

At the same time, Western monastics became bridges between traditions. Ajahn Sumedho (b. 1934), an American disciple of Ajahn Chah, established Amaravati Monastery and other forest monasteries in the UK, showing that Vinaya could be lived strictly in a modern Western setting. Ayya Khema (1923–1997), a German nun, inspired thousands of Western practitioners and called for the revival of bhikkhunī ordination. In the US, figures such as Bhikkhu Bodhi combined scholarship with socially engaged Buddhism, extending Theravāda’s relevance into contemporary society.

The Revival Theme

Each of these contributions was not isolated. Together, they revived Theravāda by ensuring that the words of Gautama Buddha were not confined to Asia but became part of global discourse. Western scholarship preserved the Canon at a critical moment in history, when colonialism, war, and modernity threatened to erode traditional lineages. By systematizing, editing, and translating, these scholars gave the Dhamma a new lifespan, one that transcends geography and culture.

Without this painstaking linguistic, historical, and spiritual work, Theravāda would not be as widely studied, practiced, or respected today. The presence of Theravāda in Canada itself, and the ability of practitioners here to engage directly with the words of Gautama Buddha, is a fruit of this revival.

8. Mindfulness and the Western Embrace of Buddhist Practice

The revival of Theravāda Buddhism in the modern world has not only been a matter of scholarship and translation, but also of practice. One of the most significant contributions of Gautama Buddha’s teaching to Western society has been the spread of mindfulness (sati) and meditation.

Western Buddhist Teachers

In the 1970s and 1980s, Western students who had trained in Asia began bringing the teachings back to their home countries.

- Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, and Sharon Salzberg—all of whom trained in the Theravāda traditions of Thailand, Burma, and India—founded the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Massachusetts. Their work created a strong foundation for Vipassanā practice in North America, making meditation accessible to tens of thousands.

- Ajahn Sumedho and the Thai Forest Sangha spread monastic mindfulness practice in the UK and US, showing that strict Vinaya discipline and deep meditation could thrive in Western culture.

- Bhikkhu Bodhi brought a scholarly and socially engaged perspective, applying mindfulness and compassion to issues such as poverty, climate change, and social justice.

These teachers made the inner practices of Gautama Buddha—once confined to monasteries—available to laypeople across Western society.

Mindfulness in Science and Medicine

The integration of Buddhist practice with science has been one of the most striking features of the modern revival.

- Jon Kabat-Zinn, trained in Zen and Vipassanā, founded the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program in 1979 at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. His work secularized mindfulness for clinical use, showing its effectiveness in reducing stress, anxiety, depression, and chronic pain.

- Psychologists and neuroscientists have since studied mindfulness extensively, demonstrating how it rewires the brain, improves emotional regulation, and enhances well-being.

- Today, mindfulness is used in hospitals, schools, workplaces, prisons, and even the military—an unprecedented spread of practice rooted in Gautama Buddha’s original teachings.

Merging Ancient Wisdom and Modern Science

This merging of Buddhism and science echoes Gautama Buddha’s own spirit: he encouraged inquiry, verification, and direct experience. In psychology, mindfulness has become a bridge between ancient contemplative training and modern evidence-based therapy. In neuroscience, meditation is studied as a means of neuroplastic change. Even in corporate and political life, mindfulness has shaped leadership, ethics, and awareness.

Promise and Caution

Yet, as much as mindfulness has contributed positively, there is also a risk: that it be severed from its deeper roots in renunciation and liberation. Mindfulness, in its fullest meaning, is not only a tool for stress reduction but part of the Noble Eightfold Path, leading beyond suffering to Nibbāna.

Thus, the task for Canadian and Western Theravāda communities is twofold:

- Appreciate the widespread benefits mindfulness has brought to society.

- Protect the deeper spirit of the practice, ensuring that it remains connected to the Vinaya, the Dhamma, and the goal of liberation.

9. New Age and Alternative Practices: Pros and Cons

The New Age movement arose in the 20th century as a response to materialism and rigid religion. It reflects humanity’s intrinsic multidimensional nature—the ability to connect with higher realms, channel spiritual entities, and explore subtle energies. Such capacities are universal, seen in shamanism, mysticism, and indigenous traditions. At its heart, the New Age reflects a deep hunger for transcendence.

Pros — Valuable Contributions

- Reawakening Multidimensional Humanity: New Age practices highlight humanity’s innate ability to connect beyond the physical plane.

- Breaking Sectarian Boundaries: Encouraged openness to Eastern traditions, paving the way for Theravāda and mindfulness to enter the West.

- Popularizing Meditation and Awareness: Teachers like Alan Watts and Ram Dass inspired mass audiences to explore presence, meditation, and inner life.

- Integration with Psychology: Thinkers like Carl Jung, Abraham Maslow, and Stanislav Grof bridged archetypes, altered states, and spiritual experience.

- Holistic Vision: Promoted ecology, vegetarianism, alternative healing, and indigenous wisdom — values harmonious with Buddhist ethics of compassion and interdependence.

Cons — Limitations and Dangers

- Lack of Full Spiritual Knowledge: Without a deep framework like the Dhamma, seekers lack reverence and often mistake passing experiences for ultimate truth.

- Indulgence: Instead of renouncing sensual craving, some movements indulged it under spiritual pretexts, scattering life energy.

- Misuse of Consciousness Foods: Substances like LSD were used without proper understanding or discipline. While they may open temporary doorways, they also led to destabilization, addiction, and societal fear. The misuse provoked bans, cutting off even the possibility of careful, beneficial exploration.

- Commercialization: Spiritual hunger exploited through products, workshops, and therapies.

- Attachment to Realms: Contact with higher beings, altered states, or astral travel was often mistaken as liberation, keeping practitioners bound to the cycle of realms.

Balanced Engagement

New Age spirituality shows the promise and peril of human multidimensional potential.

- Promise: It demonstrates the hunger for transcendence, the rediscovery of humanity’s ability to connect with higher dimensions. It also brings forward fragments of cosmic knowledge — glimpses of other realms, beings, and energies — which can inspire reverence and remind us that existence is vast and layered. This widening of vision is not without value; it expands human imagination beyond the merely material and confirms that we are more than physical beings.

- Peril: Yet without deep knowledge, discipline, and renunciation, this hunger often degenerates into indulgence, misuse, and social backlash. The absence of a framework like the Vinaya leaves seekers vulnerable to scattering life energy, mistaking temporary experiences or cosmic insights for ultimate truth.

Theravāda, rooted in Gautama Buddha’s rediscovery of the ancient path, provides the completion: it acknowledges humanity’s multidimensional nature and even the reality of higher realms, but guides practitioners to move beyond fascination with cosmic knowledge. Through Vinaya, mindfulness, and wisdom, it directs life energy not merely upward into higher realms but out of all realms, into the deathless Nibbāna..

Comparison: New Age vs. Gautama Buddha’s Path

| Aspect | New Age / Alternative Practices | Gautama Buddha’s Dhamma & Vinaya |

|---|---|---|

| Aim / Goal | Accessing higher realms, channeling spirits, union with cosmic consciousness, exploring multidimensional being | Liberation (vimutti) beyond all realms; cessation of rebirth; realization of Nibbāna — the deathless, unconditioned |

| Approach | Exploration of altered states, energies, channeling; often unstructured | Systematic training: Sīla → Samādhi → Paññā |

| Ethics | Flexible, experiential, often without strict moral restraint | Structured ethics (Vinaya, precepts) as foundation for practice |

| Practice of Energy | Awakening latent capacities (kundalini, astral travel, psychedelics) | Sublimation of life energy through brahmacariya, mindfulness, meditation |

| Discipline | Minimal; risks indulgence and scattering | Vinaya central: channeling body, speech, mind toward freedom |

| Use of Substances | Misuse of “consciousness foods” (e.g., LSD), leading to destabilization and bans | No reliance on substances; liberation through purified citta in samādhi |

| Attitude to Desire | Sometimes integrates sensuality (e.g., “sacred sexuality”) | Renunciation of craving (taṇhā), especially sensual craving (kāma-taṇhā) |

| Doctrinal Foundation | Multidimensional but vague; lacks coherent path | Clear framework: Four Noble Truths, Noble Eightfold Path, Dependent Origination |

| Result | Inspiration, temporary healing, higher-realm connection; but risk of indulgence and misuse | End of rebirth, realization of Nibbāna — ultimate liberation |

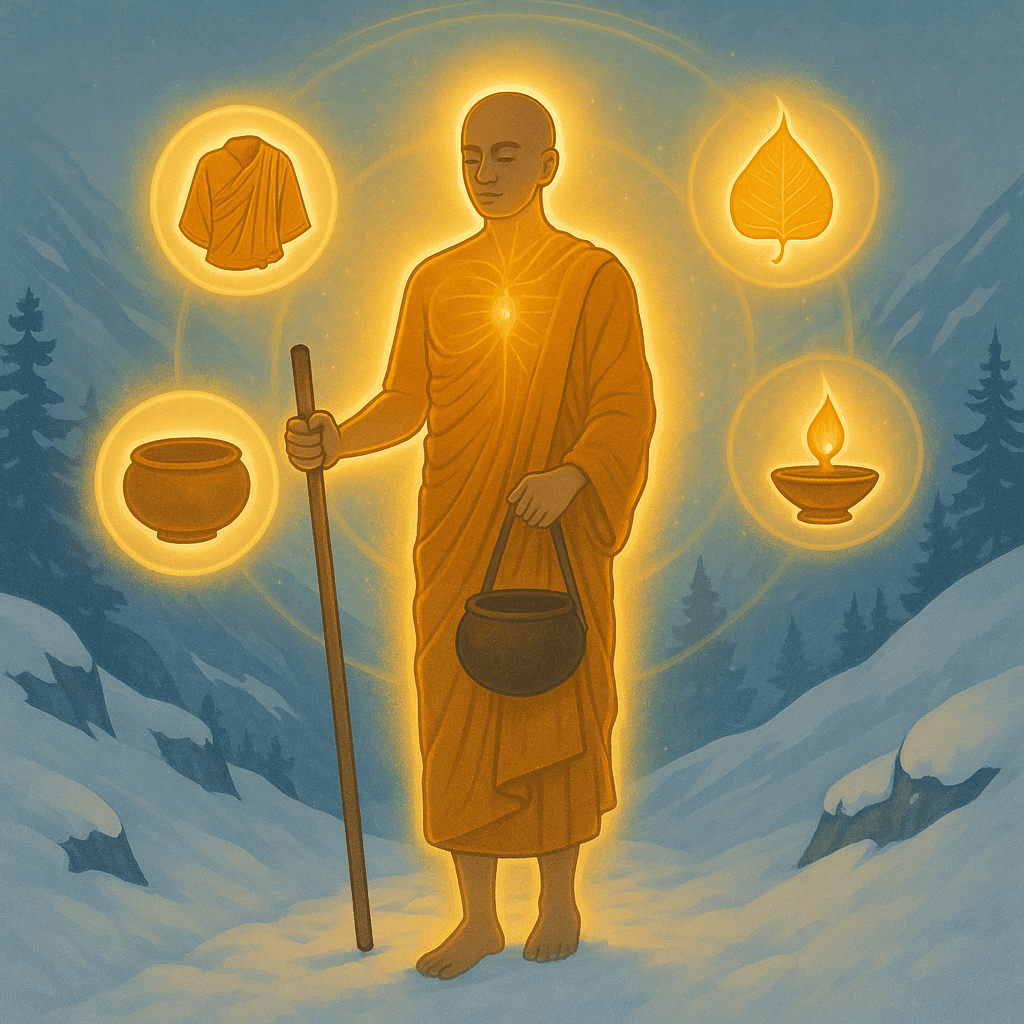

10. Toward a Canadian Theravāda Vinaya Model

The task before us is not to create a “new Vinaya,” nor to alter the rules according to convenience, but rather to live the ancient discipline faithfully within Canadian conditions. The Vinaya is timeless, but it is also adaptable — not in its essence, but in its external forms. Just as the Sangha in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, or Thailand has lived faithfully under different climates and cultures, so too can the Sangha in Canada embody the same spirit, even under new circumstances.

Celibacy Remains Inviolable

The very foundation of the holy life (brahmacariya) is celibacy. This is not negotiable, for it converts the strongest human energy into energy for liberation. Gautama Buddha said in MN 29 (Mahāsāropama Sutta):

“Na kho panetaṃ brahmacariyaṃ vussati ādibhūmiṃ paharitvā… api ca kho uttamena atthena brahmacariyassa vussati: anupādāya āsavehi cittaṃ vimuttaṃ.”

“This holy life is not lived for gain or honor… but for the supreme goal: the mind liberated from the taints through non-clinging.”

Even in a permissive society like Canada, celibacy proclaims the possibility of a freedom deeper than indulgence: freedom from craving itself.

Simplicity of Life

The monk’s life remains simple: robes, bowl, restraint, meditation. Gautama Buddha often praised appicchatā (fewness of wishes) and santuṭṭhi (contentment).

“Appicchatā ca santuṭṭhitā ca—etaṃ ariyānaṃ dhammaṃ.” (AN 4.28)

“Fewness of wishes and contentment — this is the teaching of the noble ones.”

Even if food arrives by car rather than alms-round, or heating is needed for survival, the spirit of simplicity must remain.

The Centrality of the Pātimokkha

The pātimokkha remains the living heartbeat of the Sangha. As MN 44 says:

“Yattha sabbapāpassa saṃvarā, sabbapāpassa paṭiviratā, sīlasmiṃ samādānaṃ—ayaṃ vuccati pātimokkho.”

“Restraint from all evil, abstinence from all evil, undertaking of virtue—this is called the Pātimokkha.”

In Canada, this must continue unfailingly, even if communities are small and scattered. The Sangha lives when the pātimokkha is recited.

Minimal and Transparent Adaptations

- Money: Only for necessities, ideally handled by lay stewards.

- Transportation: Only when essential, not for indulgence or social distraction.

- Food: Dependence on lay generosity remains the principle.

- Legal Duties: Fulfilled with lay assistance, but without entanglement.

Adaptation is permitted, indulgence is not. The test is always: does this pull the mind into the world, or free it from it?

Health Independence: Self as Refuge

Gautama Buddha taught in Dhp 160:

“Attāhi attano nātho, ko hi nātho paro siyā?”

“One’s Self is one’s own refuge — who else could be the refuge?”

For Canadian monastics, this means not reliance on the medical system or government, but reliance on discipline, knowledge, and practice. Freedom means caring for one’s health naturally, without constant dependence on doctors, dentists, and medicines.

Gautama Buddha himself described four supports of a bhikkhu’s life:

- Cīvara (robes)

- Piṇḍapāta (almsfood)

- Senāsana (lodging)

- Bhesajja-parikkhāra (medicines and necessities) (MN 2)

But medicines were simple: roots, leaves, honey, ghee. To live the Vinaya in Canada means to return to this simplicity, rather than the endless complexity of modern pharmaceuticals.

Ancient Cleansing Wisdom

Ancient yogic and āyurvedic practices protect health simply and naturally:

- Enema (basti): Detoxifies intestines, prevents disease.

- Oil pulling (gandūṣa): Protects teeth, preventing costly dental problems.

- Herbal remedies: Strengthen immunity without entanglement in medical bureaucracy.

This is in line with AN 5.4, where Gautama Buddha praises moderation in food and care for the body as supports for practice.

Diet as Medicine

In the West, ultra-processed foods and fast food bring obesity, diabetes, and chronic illness. For the Sangha, these are spiritual dangers, as they weaken body and mind. Gautama Buddha said in SN 46.2:

“Āhāraṭṭhitikā, bhikkhave, sattā; āhārapaccayā sattā tiṭṭhanti.”

“Beings subsist on food; beings endure because of food.”

Thus, food is medicine (āhāra-bhesajja). A whole-food, plant-based diet keeps the body light, supports meditation, and aligns with compassion (no killing), sustainability, and restraint. It is both health and Dhamma.

Prāṇāyāma and the Energy Body

Prāṇāyāma is more than breath control — it is the conscious cultivation of prāṇa, the life energy (viriya, qi, chi) that flows through the subtle channels of the body. This relates to what many modern traditions call the energy body: the multidimensional field that sustains vitality, awareness, and higher perception.

When the energy body is weak, the mind is restless, scattered, and pulled into craving or dullness. When strong and balanced, it becomes the stable foundation for both health and meditation.

- For health: Prāṇāyāma strengthens the life currents, preventing stagnation, disease, and depletion.

- For meditation: A strong energy body supports clarity, vitality, and resilience, enabling the citta to settle.

- For samādhi and psychic power: When prāṇa (viriya) is refined and directed, the mind naturally deepens into concentration and awakens its higher capacities (iddhi).

Prāṇa as Viriya

In the Dhamma, prāṇa corresponds to viriya — energy, effort, vitality. Viriya is one of the five spiritual faculties (pañc’indriya) and one of the seven factors of awakening (bojjhaṅga). Most importantly, it is the very foundation of the iddhipāda (the four bases of psychic power):

- Chanda (aspiration, zeal)

- Viriya (energy, effort)

- Citta (focused mind)

- Vīmaṃsā (investigation, inquiry)

Of these, viriya is the driving current. Without energy, aspiration collapses, the mind scatters, and inquiry is shallow. With energy, all bases align, and extraordinary potentials unfold.

As the Buddha said in the Viriya Iddhipāda Sutta (SN 51.13):

“Katamo ca, bhikkhave, viriya-samādhi iddhipādo… so taṃ viriyaṃ āsevitāya bhāvitāya bahulīkatāya… samādhiṃ samāpajjati. Ayaṃ vuccati viriya-samādhi iddhipādo.”

“And what, bhikkhus, is the basis of psychic power consisting in concentration founded on energy? Here a bhikkhu generates energy… and by cultivating, developing, and making much of that energy, he enters upon concentration. This is called the basis of psychic power that is concentration founded on energy.”

Complementary Knowledge Systems

Theories of chakras, subtle bodies, and cosmic energies — as developed in yogic, Daoist, and New Age traditions — describe the same reality of human multidimensionality from another perspective. They do not contradict the Buddha’s teaching but complement it.

- The chakra model describes how prāṇa flows through subtle centers of vitality.

- The Dhamma shows how viriya, when directed, becomes the energetic base for liberation.

- Together, these systems enrich our understanding: one maps the subtle field of energy, the other directs that energy toward the unconditioned.

More knowledge inspires deeper reverence. By integrating insights across traditions, practitioners gain a fuller picture of the energy body, its potentials, and its dangers — always remembering that the completion lies in using this vitality not for higher rebirths or cosmic experiences, but for nibbidā, virāga, and vimutti.

Fusion of Eastern and Western Knowledge

The Canadian Sangha is uniquely placed to integrate wisdoms:

- Eastern traditions provide cleansing, diet, prāṇāyāma, Vinaya.

- Western science confirms these benefits: plant-based diets reduce disease, mindfulness rewires the brain, meditation heals trauma.

By weaving these together, the Canadian model achieves independence: a life free from dependency on the medical system, free from unhealthy diets, free from social entanglement — sustained by discipline, wisdom, and practice.

Faithfulness, Not Compromise

This Canadian model is not innovation, but faithful application. It shows that:

- Celibacy endures.

- Simplicity endures.

- Pātimokkha endures.

- Health and life are sustained through natural discipline, not dependency.

As long as these endure, the Dhamma endures. AN 8.51 reminds us:

“Yāva tiṭṭhati Vinayo, tāva tiṭṭhati Saddhammo.”

“As long as the Vinaya endures, the True Dhamma endures.”

Thus, the Canadian Sangha demonstrates that Gautama Buddha’s Vinaya can live anywhere, if its spirit is preserved — independent, simple, and free.ess. Its aim is to show that the Vinaya can live anywhere, if its spirit is guarded.

11. Conclusion — The Spirit Remains Untouched

The Vinaya is the living heart of Gautama Buddha’s dispensation. It is not merely a set of rules, but the structure that shields renunciants from worldly distraction and directs life energy toward liberation. It guards the holy life, preserves celibacy, restrains the senses, and points the citta away from the world toward the deathless.

In Canada, adaptation is unavoidable. Bank accounts, cars, or taxes may be necessary external forms. But these do not touch the essence. As long as practitioners discern necessity from distraction, preserve celibacy, simplicity, and meditation, and continue the pātimokkha discipline, the spirit of Vinaya remains intact. Adaptation is not compromise when guided by renunciation.

Indeed, Canada may even offer advantages for the Vinaya’s survival: vast solitude, freedom of conscience, diversity, and intellectual openness. Here the Vinaya can flourish as a universal discipline — not bound to India, Asia, or sectarian Buddhism, but belonging to all humankind (manussa) and even devas. Science, psychology, and cosmic disclosures remind us that existence is vast, layered, and impermanent. They are valuable aids that broaden perspective, but the highest goal remains liberation (vimutti) beyond all realms.

The Buddha himself said in Dhp 160:

“Attāhi attano nātho, ko hi nātho paro siyā?”

“Oneself is one’s own refuge — who else could be the refuge?”

Thus the Canadian Sangha must stand not dependent on governments or medical systems, but relying on discipline, wisdom, and practice — truly free. With the support of laypeople offering wholesome food and basic needs, and with independence grounded in simplicity, monks and nuns can embody this path of self-reliance.

The Vinaya does not belong only to India, nor to Asia, nor even to “Buddhism” as a religion. It belongs to the great path of renunciation — rediscovered by Gautama Buddha, walked by sages before him, and open to all beings now. Wherever the Dhamma is practiced sincerely — whether under the heat of India, the forests of Southeast Asia, or the snowy skies of Canada — the Vinaya is alive.

Its spirit remains untouched: guarding the mind, converting life energy toward liberation, and pointing beyond this world to the deathless Nibbāna-dhātu. And as AN 8.51 (Gotamī Sutta) reminds us:

“Yāva tiṭṭhati Vinayo, tāva tiṭṭhati Saddhammo.”

“As long as the Vinaya endures, the True Dhamma endures.”

Thus we reaffirm: the Vinaya is the lifespan of Gautama Buddha’s teaching. By faithfully preserving the spirit of the Vinaya in Canada—through adaptation without compromise—we are extending not only Buddhism to a new land, but the very longevity of Gautama Buddha’s teaching for generations to come.

Leave a comment