Many today feel it: something is wrong with the world.

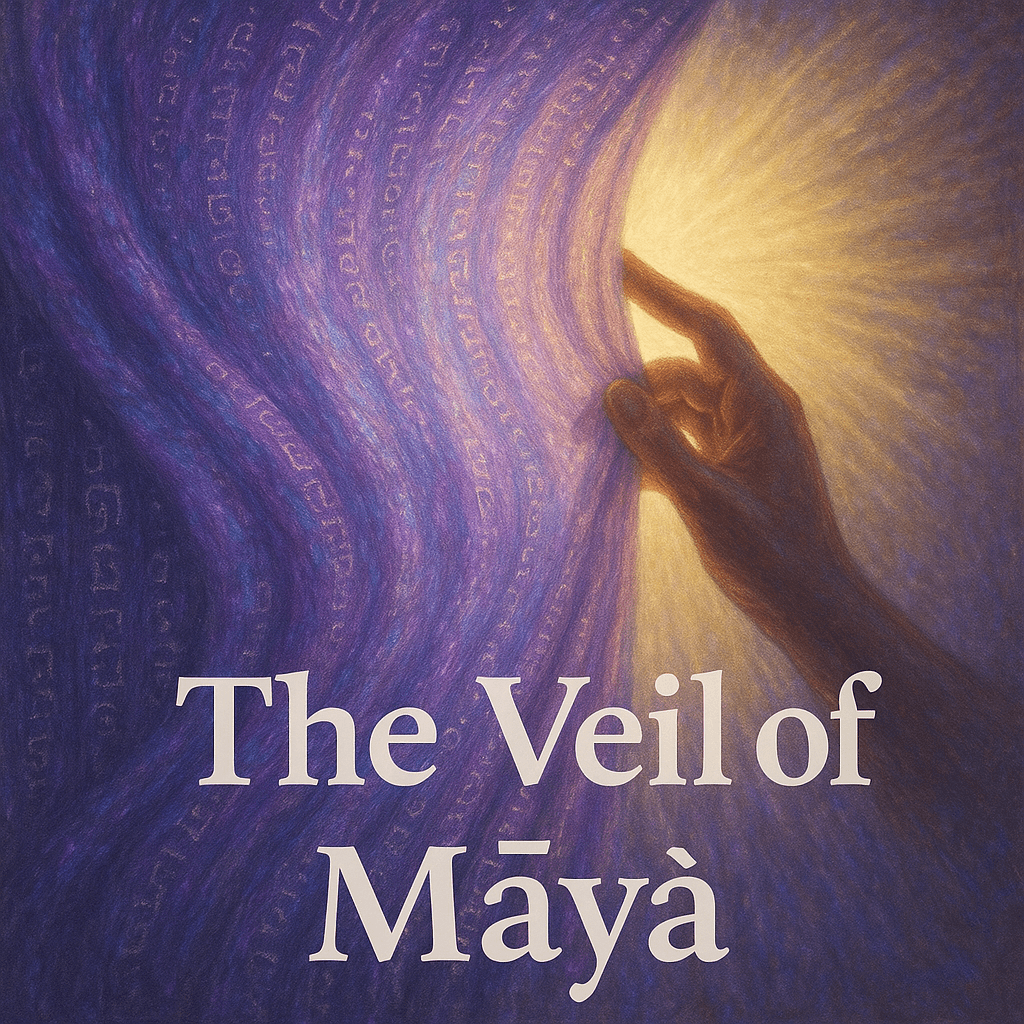

Ancient wisdom called this māyā — not just impermanent or unstable, but an illusion, not ultimately real.

Science too begins to agree. Theories suggest we may be living in a simulation: a constructed appearance that seems solid, yet is only patterns of information. Just as in a simulation, what looks real is only code—so too, in māyā, what appears real is only illusion.

The Buddha’s awakening began with this same intuition. He saw that:

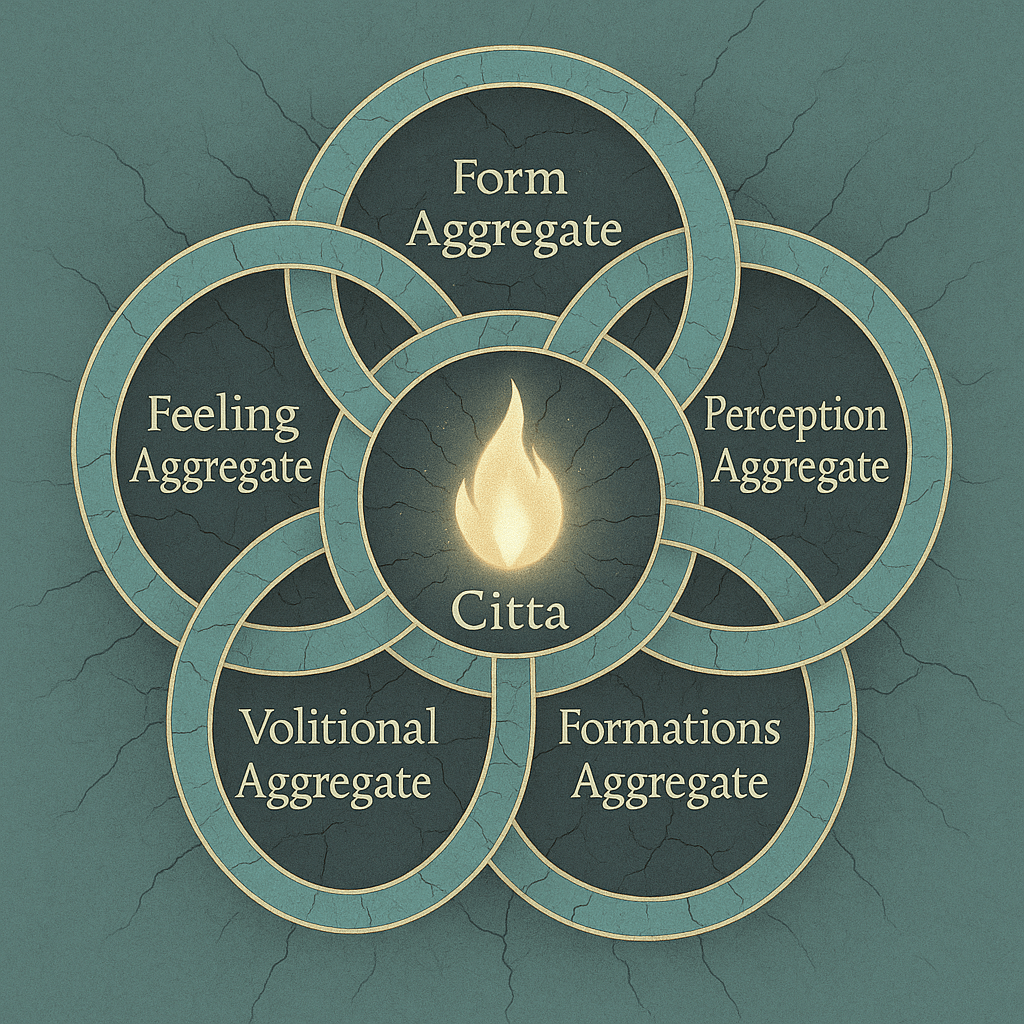

- The “worldly self” is only five fragile aggregates.

- The ego we cling to is illusion.

- Mankind is trapped in saṃsāra — an involuntary cycle of rebirth, aging, and death.

But he also discovered the way out.

🌸 Kāyagatāsati — Mindfulness Directed to the Body — turns awareness inward, opening a doorway to the measureless mind.

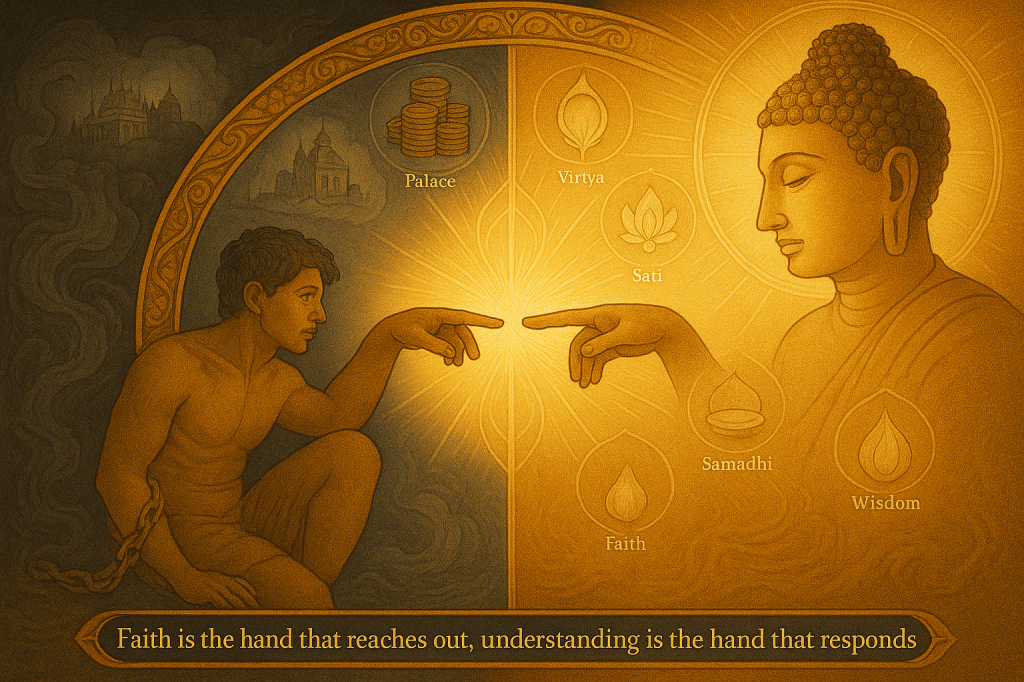

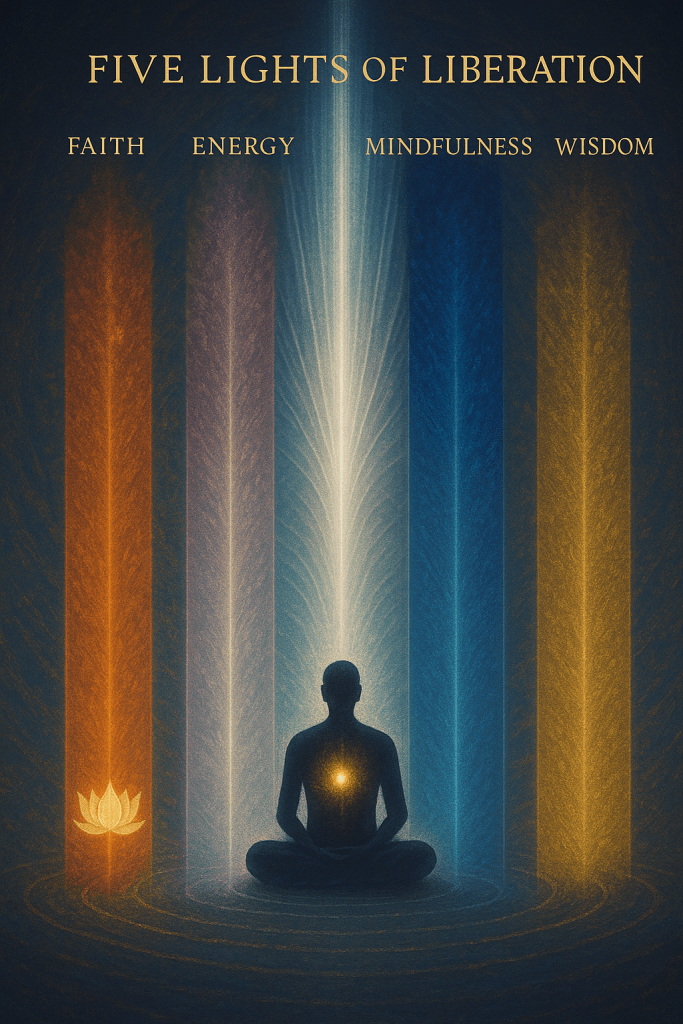

⚡ Pañca Bala — the Five Strengths (Faith, Energy, Mindfulness, Samādhi, Wisdom) — empower the citta to reach beyond the aggregates.

🌌 Samādhi — the lifting power of the mind — carries consciousness beyond the physical dimension.

💎 Vijjā-Vimutti — true knowledge and liberation — arise together: to know the nature of existence and the path beyond it.

At the end of the path lies Nibbāna-dhātu — the deathless, permanent, blissful. Not annihilation, but the cessation of worldly existence and the liberation of the real self.

The grace of Nibbāna is always subtle and near, like a hand reaching across the gap. Our practice is simply to reach back.

🕊️ This is the Right Awakening.

To see through illusion.

To walk the path of liberation.

To touch the grace of the deathless.

👉 Full essay here:

1. The Universal Intuition: “Something Is Wrong”

All over the world, across ages and cultures, human beings have carried within them a quiet unease. Even in moments of joy, even when surrounded by abundance, there lingers a whisper: “something is wrong.”

This whisper cannot be silenced by success, wealth, or comfort. It is present in kings and beggars alike, in scholars and farmers, in ancient sages and modern scientists. It is the sense that life, as it is normally lived, does not satisfy. Something is missing. Something is out of balance. Something is deeply wrong with the way existence presents itself.

The Buddha’s Awakening Began With This Intuition

The story of the Buddha begins not with mystical visions, but with this very unease. As Prince Gautama, he lived in luxury, shielded from hardship. Yet when he encountered the four sights—old age, sickness, death, and finally a wandering ascetic—he realized that life as he knew it was fragile and bound to suffering.

The Ariyapariyesanā Sutta (MN 26) records his words:

“‘I too am subject to aging, I am not exempt from aging. I too am subject to illness… I too am subject to death… Seeing this danger in what is subject to aging, illness, and death, I sought the unborn, unaging, unailing, deathless, supreme security from bondage, Nibbāna.’”

This is the archetype of the intuition: the recognition that the world as it is cannot provide lasting refuge.

Philosophers and Poets Felt It Too

Across cultures, this intuition surfaces in different forms:

- In Greek philosophy, Plato’s Allegory of the Cave depicts humanity chained in a cavern, mistaking shadows on the wall for reality. The prisoner who breaks free senses: “something is wrong here” — and begins the journey toward truth.

- In Hebrew scripture, Ecclesiastes laments: “Vanity of vanities, all is vanity” (Eccl. 1:2), pointing to the impermanence and futility of worldly striving.

- In Chinese Daoism, Laozi warns that the world’s appearances deceive, that only the Dao—the way beneath phenomena—is real.

These voices echo the same realization: the world as presented is not trustworthy.

Modern Expressions of the Same Unease

Today, we encounter this intuition in fresh guises:

- The existentialists (Camus, Sartre) described modern man’s sense of absurdity—life feels meaningless, out of joint.

- The psychologists (Frankl, Fromm) noted that even when material needs are met, people feel alienated, anxious, rootless.

- In popular culture, films like The Matrix resonate because they dramatize what many secretly suspect: the life we live may be a kind of simulation, an illusion hiding something deeper.

This is why so many feel restless in a world of endless consumption and digital distraction. Beneath the noise, the whisper remains: “something is wrong.”

The Buddha Called It Dukkha

The Buddha put this intuition into precise language. He did not dismiss it as neurosis or romantic longing. He confirmed it as a universal truth:

“Bhikkhus, birth is dukkha, aging is dukkha, death is dukkha; sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair are dukkha; association with the disliked is dukkha, separation from the liked is dukkha, not to get what one wants is dukkha; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are dukkha.” (SN 56.11, Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta)

Here, dukkha is more than “suffering.” It means unsatisfactoriness, unreliability, wrongness at the core of conditioned existence.

The intuition that “something is wrong” is nothing less than the first noble truth: the recognition that worldly existence, built upon the five aggregates, cannot fulfill.

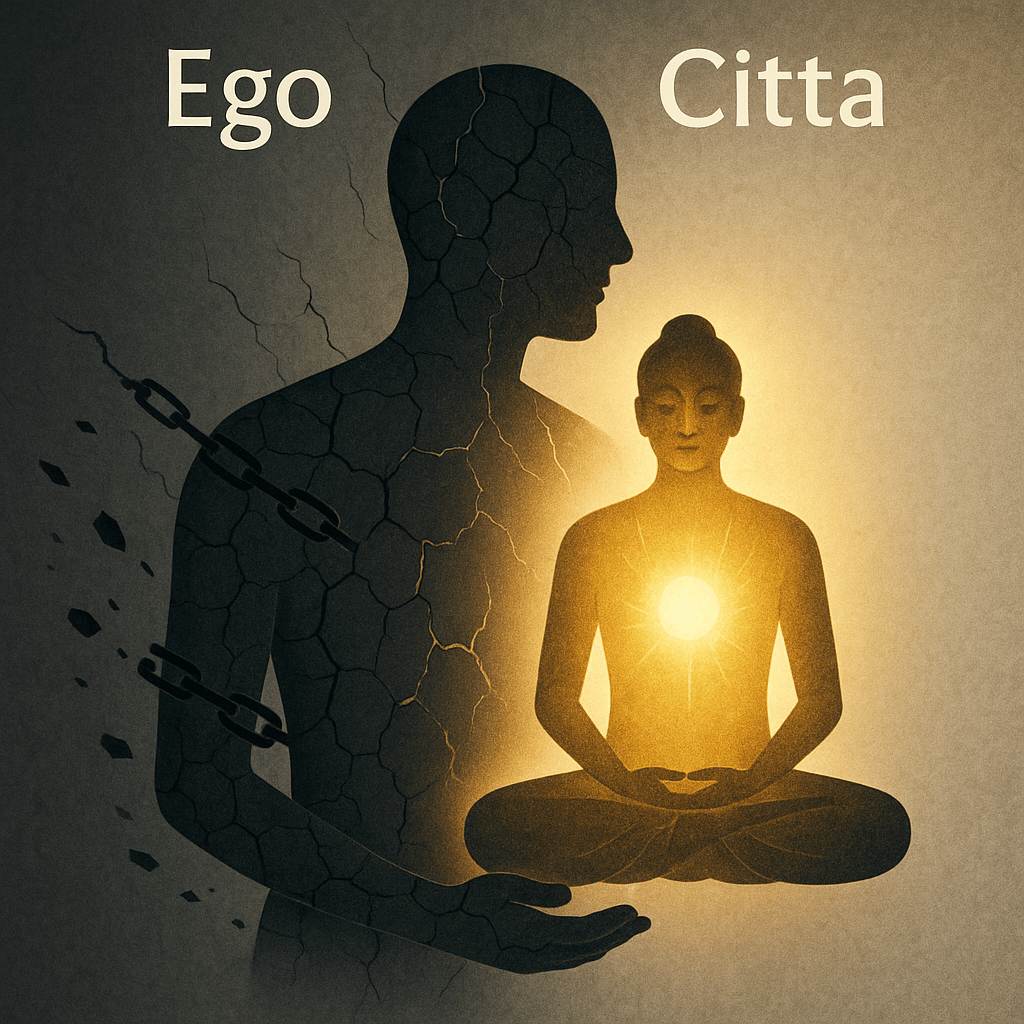

Worldly Self and Real Self

When beings cling to the five aggregates of worldly existence—form aggregate, feeling aggregate, perception aggregate, volitional formations aggregate, consciousness aggregate—they create the worldly self, or ego. This false self is fragile, conditioned, and bound to dukkha.

This is the “self” the Buddha warned against: the worldly self we cling to, which must be abandoned.

But beyond this is the real self—the true mind, the luminous citta, the soul. This is not the ego, but the deeper dimension of being that can awaken. The real self is not to be destroyed, but to be cherished and liberated from bondage to the aggregates.

Thus, when we feel “something is wrong,” it is not the real self that is wrong—it is the illusion of the worldly self. The whisper is the real self calling us to turn away from ego and toward the unconditioned.

Not Everyone Hears the Whisper

It is worth noting: not everyone responds to this intuition. Some drown it out with distraction, ambition, or denial. The Buddha spoke of this too. In the Saṃyutta Nikāya (SN 22.99), he said:

“This world is burning, afflicted by contact. It calls disease a self, though actually it is not.”

Here “self” refers to the worldly self fabricated from the five aggregates. Most people cling to this diseased, fragile identity, mistaking it for reality. Only a few recognize the wrongness and turn toward liberation.

The Noble Discontent

This pause is crucial. The feeling that something is wrong can lead two ways:

- Worldly discontent: seeking better pleasures, more refined distractions, new identities. This only strengthens the worldly self.

- Noble discontent: recognizing that no worldly solution suffices, and therefore beginning to seek the liberation of the real self, the true mind.

The second is the seed of awakening. The Buddha called it yoniso manasikāra—wise attention—the ability to turn dissatisfaction into inquiry.

A Universal Beginning Point

Thus, the intuition that something is wrong is not a flaw but a gift. It is the starting point of philosophy, art, science, and above all, spiritual practice.

- The philosopher says: something is wrong with appearances—there must be truth beyond.

- The artist says: something is wrong with the ordinary view—I must reveal a deeper vision.

- The Buddha says: something is wrong with worldly self and worldly existence—there is the unconditioned, Deathless Nibbāna.

To feel this unease is to stand at the doorway of awakening.

2. Māyā: The Ancient Recognition of Illusion

Māyā in the Vedic Vision

Long before the Buddha, the sages of India intuited that the world is not as it appears. In the Ṛg Veda, one of the oldest surviving religious texts, the word māyā often appears.

The root of māyā is mā, “to measure, to form, to build.” Originally it referred to the power of the gods to create appearances—to conjure realities that seem solid but are in fact woven of energy, perception, and mind.

A hymn to Indra proclaims:

“Indra, by your māyā you uphold heaven and earth,

you reveal the sun, you hide it again.

With māyā you shape the world of forms,

yet you yourself remain beyond them.” (Ṛg Veda 6.47.18, paraphrased)

Here, māyā is divine craftsmanship, the ability to spin the web of appearances. Later, in the Upaniṣads, the term shifts: māyā becomes the veil that hides Brahman, the ultimate reality.

Māyā in the Upaniṣads

The Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad gives perhaps the clearest statement:

“Know then that Nature is māyā,

and the great Lord is the possessor of māyā.

The whole universe is filled with beings,

who are but parts of Him.” (Śvetāśvatara Up. 4.10)

Here, māyā is cosmic illusion, the web of appearances through which beings wander, mistaking the unreal for the real. The true task is to see beyond it, to realize the formless Brahman.

This is the philosophical soil in which the Buddha was born. He inherited a culture already deeply aware that the world deceives.

The Buddha’s Reinterpretation of Māyā

The Buddha did not deny this intuition, but he gave it a sharper edge. He did not speak of māyā as a divine power, nor of Brahman hidden beneath appearances. Instead, he analyzed how illusion operates moment by moment in our perception and clinging.

One of the most striking Buddhist texts is the Phena Sutta (SN 22.95):

“Suppose, bhikkhus, that a glob of foam were floating down a river… when one with good eyesight examines it carefully, it appears empty, void, without substance. In the same way, a bhikkhu sees the form aggregate as like foam, the feeling aggregate as like a bubble, the perception aggregate as like a mirage, the volitional formations aggregate as like a plantain trunk, the consciousness aggregate as like a magic trick (māyā).”

Here the Buddha dismantles worldly existence, which is constituted by the five aggregates (pañcakkhandhā).

- The form aggregate (rūpakkhandha) is like foam, fleeting and insubstantial.

- The feeling aggregate (vedanākkhandha) is like a bubble, arising and bursting in an instant.

- The perception aggregate (saññākkhandha) is like a mirage, shimmering but unreliable.

- The volitional formations aggregate (saṅkhārakkhandha) is like a hollow plantain trunk, empty of core.

- The consciousness aggregate (viññāṇakkhandha) is like a conjurer’s trick, an appearance without essence.

Thus, worldly existence itself is māyā.

Worldly Self and Real Self in the Buddha’s Framework

The worldly self (ego) arises when beings cling to these five aggregates of worldly existence. This false identity is fragile, conditioned, and bound to dukkha.

This is the “self” that the Buddha declared as impermanent (anicca), unsatisfactory (dukkha), and not-self (anattā). It is the worldly self we must abandon.

But the Buddha did not teach nihilism. Beyond the illusion of the ego lies the real self—the true mind, the luminous citta, the soul. This is not a constructed identity but the unbound dimension of being that can incline toward the unconditioned.

Thus the path is twofold:

- Abandon the worldly self by seeing the aggregates as illusion-like.

- Cherish and liberate the real self by turning it toward Nibbāna.

Māyā in Greek Philosophy

Amazingly, similar insights arose independently in the West.

Plato, in his Allegory of the Cave (Republic, Book VII), describes prisoners chained inside a cavern. They see only shadows cast on the wall by objects passing in front of a fire. They take the shadows as real, never suspecting the greater world outside.

Plato’s allegory is another description of māyā: the world of appearances is shadow, and truth lies beyond.

Māyā in Gnostic Christianity

Early Christian mystics, especially the Gnostics, echoed the same idea. They described the material world as the work of a lower power, a deceiver who traps souls in matter. Salvation, they taught, lies in awakening to the divine light beyond the false creation.

Though different in theology, the intuition is the same: the world is not what it seems. Something greater calls us beyond.

Māyā in Chinese Daoism

In China, Daoist sages also spoke of illusion. Zhuangzi wrote of the world as a dream:

“Once Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly…

He did not know if he was Zhou who dreamed of being a butterfly,

or a butterfly now dreaming he was Zhou.”

Here illusion is not only cosmic but personal. Our very worldly self is fluid, dreamlike, unreliable.

The Buddha’s Contribution: Illusion and Liberation

What distinguishes the Buddha is not merely naming the world as illusion, but showing how to be free from it.

The problem is not only that the world is deceptive, but that beings cling to deception, constructing the worldly self out of the five aggregates of worldly existence.

This clinging turns illusion into bondage. And the way out is not through speculation, but through practice: mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom—directing the real self toward freedom.

The Māyā of the Worldly Self

The worldly self—the ego built from the aggregates—is māyā.

But the real self, the true mind (citta), is not to be abandoned. It is to be cultivated, purified, and finally freed from worldly existence. The task is not annihilation but transcendence: liberating the real self from the false shell of the worldly self.

Modern Science and Māyā

Contemporary science resonates with this ancient intuition:

- Physics: Matter is mostly empty space, structured by probabilities.

- Neuroscience: The brain constructs a model of reality; perception is a simulation.

- Psychology: The narrative ego is fragmented and illusory, confirming the Buddha’s analysis of the aggregates.

Science thus corroborates the Buddha’s teaching: what we call “the self” in ordinary life is merely a worldly self fabricated from aggregates, not the real self that can awaken.

The Danger of Wrong Awakening

Yet, as the Buddha warned, recognizing illusion can lead astray. Some, upon glimpsing that the world is not real, turn to escapism, nihilism, or conspiracy. They trade one worldly self for another, still trapped in māyā.

This is wrong awakening. True liberation requires abandoning the worldly self while directing the real self toward the unconditioned.

From Māyā to Nibbāna

The Buddha pointed to the escape:

“Atthi, bhikkhave, ajātaṃ abhūtaṃ akataṃ asaṅkhataṃ …” (Udāna 8.3)

“There is, bhikkhus, the unborn, the unmade, the unconditioned. Were there not this unborn, unmade, unconditioned, there would be no escape from the born, the made, the conditioned.”

Thus, beyond the māyā of worldly existence and the illusion of the worldly self lies Nibbāna, the unconditioned.

Practical Implication

Recognizing the five aggregates of worldly existence as illusion-like allows us to loosen our grip:

- We stop identifying with the form aggregate, and see the body as passing foam.

- We stop being enslaved by the feeling aggregate, chasing and fleeing sensations.

- We stop clinging to the perception aggregate, knowing labels are mirage.

- We see the volitional formations aggregate as karmic habits, not essence.

- We see the consciousness aggregate as conditioned knowing, not the real self.

When these are seen as mere worldly existence, the real self is no longer bound. The citta is free to turn toward the unconditioned.

3. Modern Science Parallels

The Meeting of Ancient Insight and Modern Discovery

When ancient sages described the world as māyā, an illusion, they spoke from direct meditative vision. Today, scientists using microscopes, telescopes, and brain scanners are reaching a similar conclusion: the world is not what it appears.

Modern physics, neuroscience, and psychology provide striking confirmations of the Buddha’s teaching: what we call “reality” is a construction, what we call “self” is fabricated, and what we cling to as solid is fragile and conditioned.

Physics: Matter Is Not Solid

At the everyday level, we see tables, mountains, bodies, and assume they are solid and enduring. Yet physics reveals a different picture.

- Atomic structure: Atoms are 99.9999% empty space. What seems solid is mostly void, with particles buzzing in probabilistic clouds.

- Quantum fields: Particles themselves are not tiny billiard balls but excitations of underlying fields. The “form aggregate” of worldly existence is, at its root, wave-like fluctuations, not lasting substance.

- Relativity: Even space and time are not absolute, but warped by mass and energy.

Thus the form aggregate (rūpakkhandha), which we treat as the basis of the self, is insubstantial. It is foam, just as the Buddha said.

To cling to this and say “this is me, this is mine, this is my self” is to build identity on emptiness. The worldly self (ego) that takes the form aggregate as essence is bound to frustration.

But the real self (citta / soul) is not identical with these molecular appearances. It can recognize their conditioned, illusory nature and detach from them.

Neuroscience: The Brain Constructs Reality

Neuroscience adds another layer. What we see, hear, taste, and touch is not the world itself but a construction of the brain.

- Predictive processing: The brain does not simply record input. It generates predictions and compares sensory data against them. What we experience is a “controlled hallucination.”

- Blind spot: Each eye has a blind spot where the optic nerve enters. Yet we never see a hole—because the brain fills it in.

- Color perception: Colors are not inherent in objects. They are wavelengths of light interpreted by our nervous system.

Thus, the perception aggregate (saññākkhandha) of worldly existence is demonstrably illusion-like. The Buddha compared it to a mirage shimmering in the desert.

To cling to perception as if it were ultimate truth is to live in māyā. The worldly self depends on these shifting, constructed perceptions, mistaking them for reality.

The real self (citta) can turn awareness back upon perception itself, seeing its nature as constructed, and thus loosen the bonds of delusion.

Psychology: The Ego as Narrative Construction

Modern psychology confirms that the “self” is not a fixed entity but a narrative process.

- Split-brain experiments: When the two hemispheres are disconnected, each can act independently, showing that “self” is not unitary.

- Memory studies: Our autobiographical memory is constantly rewritten; we misremember, reinterpret, and fill in gaps.

- Social psychology: Identity shifts depending on context—roles, group belonging, cultural conditioning.

Thus, the volitional formations aggregate (saṅkhārakkhandha) and the consciousness aggregate (viññāṇakkhandha) together fabricate the sense of continuity we call “I.”

This is the worldly self, or ego—an emergent fiction created by aggregates of worldly existence.

The Buddha said:

“Bhikkhus, just as a magician or his apprentice conjures a magical illusion… so too, what is called consciousness aggregate is like a magic trick.” (SN 22.95, adapted to stress aggregate)

The consciousness aggregate of worldly existence is māyā: a conjuring.

Yet the real self (citta)—pure, unaggregated consciousness—is not the same as this conjured stream. It is broader than the aggregates, capable of transcending them. It is what can awaken from the dream of ego.

Emotions and the Feeling Aggregate

Modern affective neuroscience shows that feelings are bodily states interpreted by the brain. Fear, joy, anger—though compelling—are waves of hormones and neural patterns.

The Buddha called the feeling aggregate (vedanākkhandha) a bubble: arising, bursting, vanishing.

Yet most people identify with feelings: “I am angry. I am happy. I am afraid.” Thus the worldly self is constructed and re-constructed in every moment of feeling.

Modern research shows how fragile this is. Drugs, trauma, or brain stimulation can radically alter feelings and thus alter “who I am.” This exposes how thin the worldly self is.

The real self, however, can step back and observe feelings without clinging. In this mindfulness, the bubble bursts and the mind remains free.

Consciousness Aggregate vs. Pure Consciousness

This is where nuance is essential.

Even consciousness—the knowing process—seems self-evident. “Surely,” we think, “the one who is aware is my true self.”

But the Buddha placed the consciousness aggregate (viññāṇakkhandha) firmly within worldly existence. It arises dependent on contact: eye with forms, ear with sounds, mind with thoughts. It is conditioned, impermanent, and bound to the laws of this universe—including aging and death. When pure consciousness becomes aggregated, it is woven into the fabric of saṃsāra.

This is why the Buddha compared the consciousness aggregate to a magic trick. It is not ultimate reality.

Yet, this does not mean that all consciousness is illusion. The unaggregated consciousness—the pure citta, the real self or soul—is beyond the aggregates. It is luminous, unconditioned by worldly forms, and not subject to the decay of the universe.

The task is not to annihilate consciousness but to distinguish:

- Abandon the consciousness aggregate as not-self.

- Liberate pure consciousness (citta) to abide beyond worldly existence.

The Simulation Hypothesis

In popular science and philosophy, the “simulation hypothesis” has captured imaginations: perhaps our universe itself is a computer simulation. While speculative, it resonates because it echoes the ancient intuition: the world is staged, illusory, not ultimate.

From the Buddha’s view, whether or not we are in a literal simulation is secondary. What matters is that the worldly existence we experience through the five aggregates—including the consciousness aggregate—is already māyā.

But beyond the simulation lies the real self, the unaggregated citta, capable of awakening to Nibbāna.

The Real Self Beyond Māyā

Here the Buddhist view diverges from both materialist science and idealist philosophy. Modern science often reduces mind to matter, while some philosophies reduce matter to mind. The Buddha’s teaching avoids both extremes.

- The five aggregates of worldly existence are conditioned and illusion-like.

- The worldly self (ego) arises from clinging to them.

- The real self—the luminous citta, the pure unaggregated consciousness—is not reducible to the aggregates.

This luminous mind is obscured by defilements but can be purified. The Buddha spoke of it as:

“Pabhassaram idaṃ, bhikkhave, cittaṃ. Tañca kho āgantukehi upakkilesehi upakkiliṭṭhaṃ.” (AN 1.49–52)

“Bhikkhus, this mind is luminous, but it is defiled by visiting impurities.”

When freed of defilements, the real self shines in its unaggregated purity.

Bridging Ancient and Modern

When we put this all together:

- Physics shows the form aggregate is not solid.

- Neuroscience shows the perception aggregate is constructed.

- Psychology shows the volitional formations and consciousness aggregates fabricate the worldly self.

- Affective science shows the feeling aggregate is fragile and fleeting.

All confirm the Buddha’s vision: the worldly self is māyā, and worldly existence cannot be ultimate.

Yet the Buddha goes beyond science: pointing to the real self—the unaggregated consciousness, the luminous citta—which can be liberated from the aggregates.

Practical Implications

Modern science, then, is not a replacement for Dhamma but a mirror. It shows us how unstable the worldly self is.

The practice is to:

- See the five aggregates of worldly existence as processes, not “me” or “mine.”

- Abandon clinging to the worldly self fabricated from them.

- Distinguish between the consciousness aggregate (illusion-like) and pure unaggregated consciousness (citta).

- Cherish and cultivate the real self, directing it toward the unconditioned, Nibbāna.

4. The Buddhist Lens: Seeing Through the Illusion

Beyond Naming the Illusion

Many traditions, as we have seen, speak of illusion. The Vedas named it māyā. Plato spoke of shadows. Daoism of dreams. Science today calls it perception, cognition, or simulation.

But the Buddha went beyond naming the illusion. He dissected how the illusion arises, how the worldly self is fabricated, and how the real self can be freed.

This is why his teaching is called the Dhamma-vinaya: the doctrine and discipline that does not merely describe, but shows the path of practice to liberation.

The Three Poisons: The Architects of Māyā

At the heart of the Buddha’s analysis are the three unwholesome roots:

- Rāga — craving, attachment, lust for becoming.

- Dosa — aversion, hatred, resistance.

- Moha — delusion, ignorance, confusion.

These are the architects of illusion. They weave the five aggregates into a fabric that we mistake for reality.

- Through rāga, we cling to the form aggregate as “my body” and to the feeling aggregate as “my happiness.”

- Through dosa, we resist what displeases us, reinforcing the perception aggregate with distorted views.

- Through moha, we mistake the volitional formations aggregate and the consciousness aggregate for a lasting “I.”

Thus the worldly self (ego) is fabricated. It is not given, it is constructed moment by moment through craving, aversion, and delusion.

Dependent Origination and the Worldly Self

The Buddha explained this fabrication in the teaching of dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda).

“With ignorance as condition, volitional formations; with volitional formations as condition, consciousness; with consciousness as condition, name-and-form… thus does this whole mass of suffering arise.” (SN 12.1)

This is not a metaphysical chain but a description of how the worldly self comes into being.

- Ignorance (avijjā): Not seeing reality as it is.

- Volitional formations (saṅkhārā): Conditioned habits, karmic impulses.

- Consciousness aggregate (viññāṇakkhandha): Awareness woven into worldly contact, subject to aging and death.

- Name-and-form: The structure of body and mind built around this.

From there, feelings, cravings, grasping, and becoming spiral forth.

Thus the worldly self is nothing more than this conditioned chain, repeated endlessly across lives.

The Illusion of the Worldly Self

When beings cling to the five aggregates of worldly existence, they fabricate the ego.

- The form aggregate is seen as “my body.”

- The feeling aggregate is seen as “my pleasure and pain.”

- The perception aggregate is seen as “my view, my memory.”

- The volitional formations aggregate is seen as “my will, my choices.”

- The consciousness aggregate is seen as “my awareness, my soul.”

But each of these is impermanent, unsatisfactory, and not-self. Together they create a false self—the worldly self—that is māyā.

The Buddha declared:

“Bhikkhus, form aggregate is not self… feeling aggregate is not self… perception aggregate is not self… volitional formations aggregate is not self… consciousness aggregate is not self. If any of these were self, they would not lead to affliction.” (SN 22.59, Anattalakkhaṇa Sutta)

The worldly self is a disease, a false identity that guarantees suffering.

The Real Self Beyond the Aggregates

Yet the Buddha did not deny the existence of a deeper dimension. The real self—the luminous citta, the soul—is not identical with the aggregates.

The aggregated consciousness (viññāṇakkhandha) is indeed illusion-like, bound by the laws of the universe, subject to aging and death. But the unaggregated consciousness—the pure citta—is luminous, unborn, and not subject to decay.

The Buddha spoke of this directly:

“Pabhassaram idaṃ, bhikkhave, cittaṃ. Tañca kho āgantukehi upakkilesehi upakkiliṭṭhaṃ.” (AN 1.49–52)

“Bhikkhus, this mind is luminous, but it is defiled by visiting impurities.”

The visiting impurities are rāga, dosa, and moha. They cover the real self and force pure consciousness into aggregation, binding it to worldly existence.

The practice of the Dhamma is to remove these impurities so that the real self shines forth, unbound.

Two Movements: Abandon and Cherish

Thus, the Buddha’s lens is clear:

- Abandon the worldly self. See the five aggregates of worldly existence as impermanent, unsatisfactory, and not-self. Release clinging to them.

- Cherish the real self. Nurture the luminous citta, direct it toward freedom, and purify it from defilements.

These are not contradictory. To abandon the worldly self is to liberate the real self.

Rāga, Dosa, Moha: The Glue of Māyā

Let us return to the three poisons, for they are crucial.

- Rāga (attachment): Chains us to the form aggregate and feeling aggregate, always seeking pleasure.

- Dosa (aversion): Corrupts the perception aggregate and volitional formations aggregate, distorting the world into enemies and obstacles.

- Moha (delusion): Corrupts the consciousness aggregate, making us mistake aggregated consciousness for the real self.

As long as these three operate, the real self remains trapped in worldly existence, circling in saṃsāra.

Nibbidā: Disenchantment with the Worldly Self

The first step of liberation is nibbidā, disenchantment. When the practitioner sees the aggregates clearly, the worldly self loses its charm.

“Seeing thus, the instructed noble disciple becomes disenchanted with the form aggregate, disenchanted with the feeling aggregate, disenchanted with the perception aggregate, disenchanted with the volitional formations aggregate, disenchanted with the consciousness aggregate.” (SN 22.59)

Disenchantment is not pessimism. It is the real self awakening to the truth that worldly existence can never satisfy.

Virāga: Fading of Craving

From disenchantment arises virāga, the fading of craving. When the real self no longer seeks to prop up the worldly self, attachment loosens.

Craving fades from form, feeling, perception, volitions, and aggregated consciousness. The grip of rāga weakens. The glue of māyā dissolves.

Vimutti: Liberation of the Real Self

When craving has faded, liberation (vimutti) arises. The real self, freed from bondage to the aggregates, abides in the unconditioned.

This is not annihilation. It is the real self awakening to its true nature, no longer bound by aggregated consciousness. It is the soul returning to its luminous freedom.

Science and the Buddhist Lens

Here we see the divergence from science. Science describes how the aggregates operate. It can show us the illusions of form, perception, volition, feeling, and consciousness.

But it cannot distinguish between the worldly self fabricated from aggregates and the real self beyond them. Without the Dhamma, science leaves us knowing the prison but not the way out.

The Buddha provides the missing key: the training of sīla, samādhi, and paññā to purify the citta and reveal the luminous real self.

Practical Implication

To see through the Buddhist lens is to recognize:

- The five aggregates of worldly existence are illusion-like and must not be clung to.

- The worldly self (ego) is māyā and must be abandoned.

- The real self (citta / unaggregated consciousness) is luminous, to be cherished and liberated.

- The three poisons are what bind the real self into worldly existence.

- The path of practice—faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, wisdom—purifies the citta and frees it from aggregation.

5. Kāyagatāsati: Turning Awareness Inward—The Gateway to the Measureless Mind

The Buddha’s Emphatic Praise

Among the countless practices taught by the Buddha, very few are singled out as direct gateways to liberation. Kāyagatāsati is one of them.

In the Aṅguttara Nikāya (AN 1.570), the Buddha declared:

“Bhikkhus, if one thing is developed and cultivated, it leads to the realization of the fruit of knowledge and liberation. What is that one thing? It is kāyagatāsati (mindfulness directed to the body). This one thing, bhikkhus, if developed and cultivated, leads to the realization of the fruit of knowledge and liberation.”

Eka-dhammo, bhikkhave, bhāvito bahulī-kato vijjā-vimutti-phala-sacchikiriyāya saṃvattati. Katamo eka-dhammo? Kāyagatāsati. Ayaṃ kho, bhikkhave, eka-dhammo bhāvito bahulī-kato vijjā-vimutti-phala-sacchikiriyāya saṃvattatī ti.

This is extraordinary. While many practices are praised as supportive or preparatory, here the Buddha states unequivocally that kāyagatāsati alone, if developed, is sufficient for the full realization of liberation (vijjā-vimutti).

Why? Because directing awareness to the body dismantles the illusion of the worldly self (ego) at its root and opens the real self (citta) into its measureless dimensions.

Why the Body Is the Gateway

The form aggregate of worldly existence (rūpakkhandha) is the most grasped as “I” and “mine.” We decorate it, feed it, protect it, and fear its aging and death. The ego identifies most strongly with the body.

But the body is also the most direct way to see impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and not-self. Every breath changes. Every cell dies. The body inevitably decays. Thus, the body is both the prison of the worldly self and the doorway for the real self to be liberated.

Here we must refine the understanding:

- The heart area is the seat of the citta, the real self. It is also the gateway or doorway to higher consciousness.

- The heart itself does not hold a large reservoir of consciousness. Rather, it is the threshold through which the citta connects to other dimensions.

- Beyond this doorway, the brain consciousness functions as the vast reservoir of human consciousness for this life. It stores memories, impressions, and personality patterns.

- The citta consciousness, by contrast, is the deep continuum carrying the memory of all past lives.

Thus, in practice:

- Awareness directed to the body leads us inward to the heart gateway.

- Through the heart, the citta connects to the brain consciousness, where this-life memory and collective human consciousness reside.

- From there, the citta expands into measureless fields of consciousness—subconscious, collective, planetary, solar, galactic, and universal.

Brain Consciousness and Citta Consciousness

The brain consciousness is about this present life. It records, interprets, and constantly updates the citta with experiences from this existence. It is like the surface current of a vast ocean.

The citta consciousness is deeper—it contains the memory of all past lives, the karmic seeds, and the luminous potential for liberation. It is the deep ocean itself.

When awareness is directed inward through kāyagatāsati, the practitioner begins to experience how these two levels interact:

- The brain updates the citta with present-life data.

- The citta carries continuity from countless lives.

- Together, they shape the field of experience.

Organ Transplants and Consciousness

This layered model of consciousness helps us understand the mysterious effects of organ transplants.

Heart Transplants

- The heart is the seat and gateway of the citta.

- When the heart is transplanted, the recipient continues to function initially with their own brain consciousness—this-life memories, personality, habits.

- But over time, the donor’s citta-memory—carried with the heart—begins to influence the recipient.

- Recipients may begin to experience the donor’s memories, inclinations, or even identity.

- This results in a coexistential state (two consciousnesses overlapping) or, in profound cases, the revival of the donor’s citta within the recipient’s body.

- Thus, from the perspective of Dhamma, heart transplantation is not just biological—it can signify the end of one person and the re-emergence of another.

Liver (and Blood-Rich Organs) Transplants

- The liver, being the great reservoir of blood, carries memory and consciousness imprints.

- When transplanted, the donor’s subtle memory-patterns and knowledge are transferred to the recipient.

- This can alter tastes, tendencies, or even fragments of memory.

Blood as Carrier of Consciousness

- Blood is not inert fluid but a medium of karmic imprint.

- Memory and consciousness are carried not only in the brain but in blood and organs.

- This is why transfusions or organ transfers can produce subtle or profound personality changes.

The Sutta Framework: MN 119 Kāyagatāsati Sutta

The Kāyagatāsati Sutta (MN 119) outlines the practice in detail:

- Mindfulness of breathing—calming the body, centering awareness.

- Mindfulness of postures—observing walking, standing, sitting, lying.

- Mindfulness of bodily activities—eating, dressing, cleansing.

- Mindfulness of anatomical parts—32 body parts, dissolving infatuation.

- Mindfulness of the four elements—earth, water, fire, wind.

- Mindfulness of corpses in decay—charnel ground contemplations.

Each stage directs awareness back through the body into the heart, opening the doorway to deeper consciousness.

From Finite to Infinite Awareness

As mindfulness matures, awareness:

- Dissolves clinging to the form aggregate.

- Observes the feeling aggregate without grasping.

- Corrects distorted perception aggregate (saññā).

- Calms the volitional formations aggregate (saṅkhārā).

- Recognizes the consciousness aggregate (viññāṇa) as conditioned and limited—while touching the unconditioned citta.

Through the heart doorway, the real self then expands:

- Into the subconscious (hidden karmic impressions).

- Into collective human consciousness (the brain’s vast reservoir).

- Into earth consciousness.

- Into solar consciousness.

- Into galactic consciousness.

- Into universal consciousness (which resides in the universe, not the brain).

Universal consciousness is beyond the body. The brain is the link; the heart is the doorway. The citta travels through both to enter the measureless mind.

Samatha and Vipassanā: The Two Wings of Practice

Traditionally, Buddhist practice is described in terms of samatha and vipassanā. Many render samatha as “calm,” but this is misleading.

- Samatha is not passive tranquility. It is the cultivation of samādhi.

- Samādhi is not just concentration—it is the lifting power of the mind, the force that elevates the citta from this physical dimension into higher dimensions of consciousness.

Thus, when mindfulness is directed to the body (kāyagatāsati):

- Vipassanā (insight) dismantles illusion, showing the aggregates as impermanent, unsatisfactory, and not-self.

- Samatha (the cultivation of samādhi) empowers the citta to rise through the heart gateway, stabilize in brain consciousness, and expand into measureless fields of awareness.

The practice is therefore complete: insight frees, samādhi lifts.

Practical Instructions

- Start with the breath—follow it until awareness naturally rests in the heart.

- Anchor in the heart—recognize it as the seat and gateway of the citta.

- Allow awareness to link to brain consciousness—the field of this-life memory.

- Expand progressively—subconscious → collective → earth → solar → galactic → universal consciousness.

- Reflect on impermanence—dissect body parts, elements, and death contemplations.

- Cultivate samādhi as lifting power—let the citta rise beyond physical dimension into higher planes.

- Rest in measureless awareness—the luminous citta freed from the aggregates.

Conclusion

Kāyagatāsati is not mere body-awareness. It is:

- The dismantling of the worldly self bound to the aggregates.

- The re-centering of awareness in the heart as seat and gateway of the citta.

- The linking of the citta through brain consciousness, the reservoir of this-life experience.

- The unfolding of the measureless mind, connecting to subconscious, collective, planetary, cosmic, and universal fields.

- The union of vipassanā (seeing clearly) and samādhi (lifting power of the mind).

- The very practice singled out by the Buddha as sufficient for full liberation.

The heart is the entry, the brain is the field, and the universe is the horizon. Through kāyagatāsati, the real self travels this path and touches the grace of the deathless.

6. The Five Strengths of the Mind (Pañca Bala)

Strength for the Journey Beyond Māyā

The Buddha did not only expose illusion (māyā). He gave the inner powers needed to transcend it. The real self—the citta, seated in the heart—must pass through the brain’s reservoir of this-life consciousness and expand into measureless dimensions, until it touches the deathless.

But the citta is long entangled in rāga (craving), dosa (aversion), and moha (delusion). Without strength, it drifts back into worldly existence. With strength, it moves steadily toward liberation.

These inner powers are the pañca bala—the five strengths of the mind:

- Saddhā – Faith

- Viriya – Energy

- Sati – Mindfulness

- Samādhi – Concentration (Lifting Power of the Mind)

- Paññā – Wisdom

Together, they stabilize the heart as the gateway, guide the citta through the brain’s reservoir of this-life consciousness, and empower it to expand into the universal field.

1. Saddhā – Faith: Trust in the Heart-Gateway

Faith (saddhā) is the first strength. It is not blind belief, but a profound trust that the path is real and that liberation is possible.

The worldly self, fabricated from aggregates, is constantly doubtful. It identifies only with the brain consciousness—this-life memories and impressions—and fears death as the end. Saddhā reminds us that beyond the aggregates, the citta carries the memory of countless lives.

Faith is what allows us to trust the heart as the seat and doorway of the citta, even though the heart itself does not hold a large portion of consciousness. Through faith, we dare to enter that doorway, knowing it connects us to the brain consciousness (this life) and beyond, to the measureless consciousness of the universe.

The Buddha said:

“Just as a ship with a strong anchor does not drift with the current, so too the bhikkhu with faith established does not drift away.” (AN 6.115)

Faith anchors the citta in the heart, keeping it from being swept away by worldly doubt. It is the first step toward opening the measureless mind.

2. Viriya – Energy: Effort to Cross the Threshold

Faith provides direction, but effort carries us forward. Viriya is the heroic energy that sustains the citta through the doorway of the heart and into deeper dimensions of consciousness.

The worldly self prefers comfort, relying on the feeling aggregate to chase pleasure and avoid pain. It resists the strenuous work of meditation. But the citta, energized by viriya, refuses to remain confined to the brain’s habitual loops of perception and memory.

Viriya manifests as:

- Persistence in returning awareness to the body and breath.

- Courage to face subconscious patterns that emerge through the heart-gateway.

- Strength to endure the disorientation of expanding beyond human consciousness into planetary and cosmic fields.

The Buddha likened viriya to the steady tread of a warrior:

“Just as a strong man might stretch his arm, so too the bhikkhu arouses energy, unrelenting, firm in purpose.” (SN 51.20)

Viriya is what prevents the practitioner from stalling in the brain’s surface reservoir and carries the citta outward into measureless mind.

3. Sati – Mindfulness: Presence in the Field of Consciousness

Sati is the strength of presence. Without it, awareness flickers and scatters; with it, the citta remains steady.

The worldly self identifies with the aggregates—body, feeling, perception, volitions, and aggregated consciousness—and is always lost in the past or future. But sati anchors us in the living moment, preventing the citta from being dragged into illusion.

Practiced through kāyagatāsati (mindfulness directed to the body), sati has a specific function in the refined model:

- It begins in the heart-gateway, stabilizing the seat of the citta.

- It extends into the brain consciousness, keeping awareness present amid the vast reservoir of this-life impressions.

- It holds steady as the citta expands into collective, planetary, solar, galactic, and universal consciousness.

Sati prevents the citta from being overwhelmed by the sheer vastness of measureless mind. It is the tether of presence that keeps expansion clear and liberating.

4. Samādhi – The Lifting Power of the Mind

Here we must be precise. Samādhi is often translated as “concentration,” but this is only part of the truth.

- Samādhi is the lifting power of the mind.

- It is the force that raises the citta from its confinement in the physical dimension and carries it into higher dimensions of consciousness.

- It is cultivated through samatha practice—not as calmness alone, but as the deliberate strengthening of samādhi.

When samādhi matures:

- The heart becomes the stable base, unmoved.

- The brain consciousness becomes unified, no longer scattered across fragmented impressions.

- The citta gathers its power and is lifted upward, expanding first into the subconscious, then into the collective, and eventually into universal consciousness.

This is why the Buddha compared samādhi to a fortress wall—impenetrable, protecting the mind from invasion. But it is more than defense. Samādhi is also the launching power, the inner energy that allows the citta to rise.

In the jhānas, this power is fully visible: radiant joy, vast equanimity, and the expansion of awareness beyond body and thought. These states are not escapes—they are demonstrations of samādhi’s lifting power in action.

Without samādhi, the citta remains earthbound, tied to the aggregates. With samādhi, it rises beyond them, tasting freedom.

5. Paññā – Wisdom: Seeing Beyond Aggregates

Finally, paññā is the strength of direct knowing. It cuts through illusion by distinguishing what is worldly and what is real.

Worldly wisdom is intellectual, bound to brain consciousness. But liberating paññā arises when the citta sees directly:

- The five aggregates of worldly existence are impermanent, unsatisfactory, and not-self.

- The worldly self fabricated from them is illusion.

- The citta itself, luminous and unaggregated, is real and capable of liberation.

This wisdom is not speculative. It arises when the citta, seated in the heart, stabilized in the brain consciousness, and expanded into measureless fields, directly sees the nature of reality.

The Buddha summarized the fruit of wisdom simply:

“Just as the great ocean has one taste, the taste of salt, so too this Dhamma has one taste, the taste of liberation.” (Udāna 5.5)

Wisdom tastes like freedom because it recognizes the distinction between aggregated consciousness (illusion-bound) and unaggregated consciousness (luminous, deathless).

The Harmony of the Five Strengths

The strengths balance each other:

- Faith without wisdom is blind.

- Wisdom without faith is cynical.

- Energy without concentration is restless.

- Concentration (samādhi) without energy is sluggish.

- Mindfulness harmonizes them all, keeping balance.

Together, they stabilize the citta at the heart gateway, guide it through the brain’s human consciousness, and carry it into the vast, universal field.

Practical Integration in Meditation

When cultivating the five strengths:

- Begin with faith—trust the heart as the citta’s doorway.

- Apply energy—persist through resistance of the worldly self.

- Sustain mindfulness—remain present as awareness moves through heart and brain consciousness.

- Deepen samādhi—develop the lifting power of the mind until the citta rises into higher dimensions.

- Awaken wisdom—see the aggregates as not-self, cherish the citta, and direct it to Nibbāna.

From Strength to Liberation

With the five strengths matured, the practitioner no longer wavers:

- The worldly self weakens.

- The aggregates of worldly existence are seen as illusion.

- The citta expands into the measureless, connecting to universal consciousness.

- Finally, it transcends even universal consciousness, touching the unconditioned: Nibbāna, the deathless realm beyond all worlds.

Conclusion

The five strengths are not mere virtues. They are the engine of liberation.

- Saddhā gives confidence in the heart as gateway.

- Viriya provides the heroic energy to press on.

- Sati keeps presence steady in the vast field of awareness.

- Samādhi lifts the citta beyond the aggregates into higher dimensions.

- Paññā sees clearly and directs the citta to the deathless.

When faith, energy, mindfulness, samādhi, and wisdom are fully alive, the citta abides unshakable. The worldly self falls away. The real self stands free.

7. The Gap and the Hand of Nibbāna

The Icon of the Gap

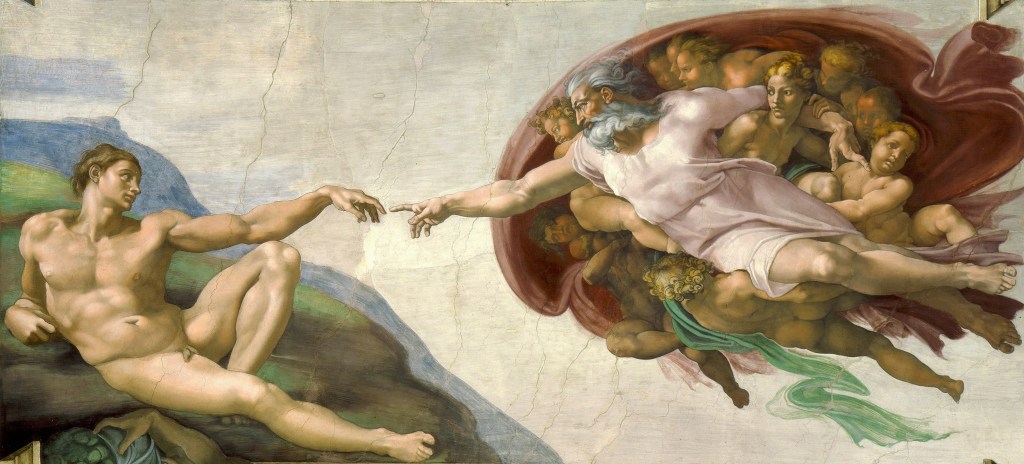

Few works of art capture the drama of existence more powerfully than Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, painted on the Sistine Chapel ceiling around 1511.

On the left, Adam reclines on the barren earth. His body is complete, yet heavy, bound by gravity. His left arm stretches toward the divine, his hand open, fingers extended—but his touch falls short.

On the right, God rushes forward, robed in a swirling mantle of angels. His right arm strains outward, His finger extended toward Adam’s. The hands nearly touch, but a small space remains—a sliver of distance that speaks of all humanity’s longing for the divine.

This gap has stirred interpreters for centuries. It represents both closeness and distance: God’s grace is near, yet man cannot quite reach.

In this visual silence—the space between fingers—Michelangelo captures the tension of the human condition: made for the infinite, but stranded in the finite.

The Christian Reading

In the Christian tradition, the fresco expresses the creation of humanity in God’s image. Adam, lifeless clay, is about to be animated by the touch of God’s Spirit. Yet in Renaissance symbolism, the scene also bears deeper meanings.

- Adam represents humanity—formed, but not yet fully alive without God’s breath. He embodies human potential and limitation.

- God represents the divine source, eternally reaching out to humanity with grace and love.

- Sophia (Wisdom) is often identified in the female figure beneath God’s left arm. She symbolizes divine wisdom, echoing Proverbs 8: “The Lord created me at the beginning of his work.”

- The Mantle as Brain – Scholars have noted that God’s swirling cloak resembles the human brain. Michelangelo, familiar with anatomy, may have depicted God enclosing consciousness itself, suggesting that the divine gift is not only life but intellect and awareness.

- Angels as Virtues – The figures surrounding God can be read as the virtues or spiritual powers that accompany divine grace—faith, hope, love, and understanding.

Thus, in Christian reading, the fresco dramatizes the moment where humanity is invited to transcend dust and share in divine life through wisdom, virtue, and grace.

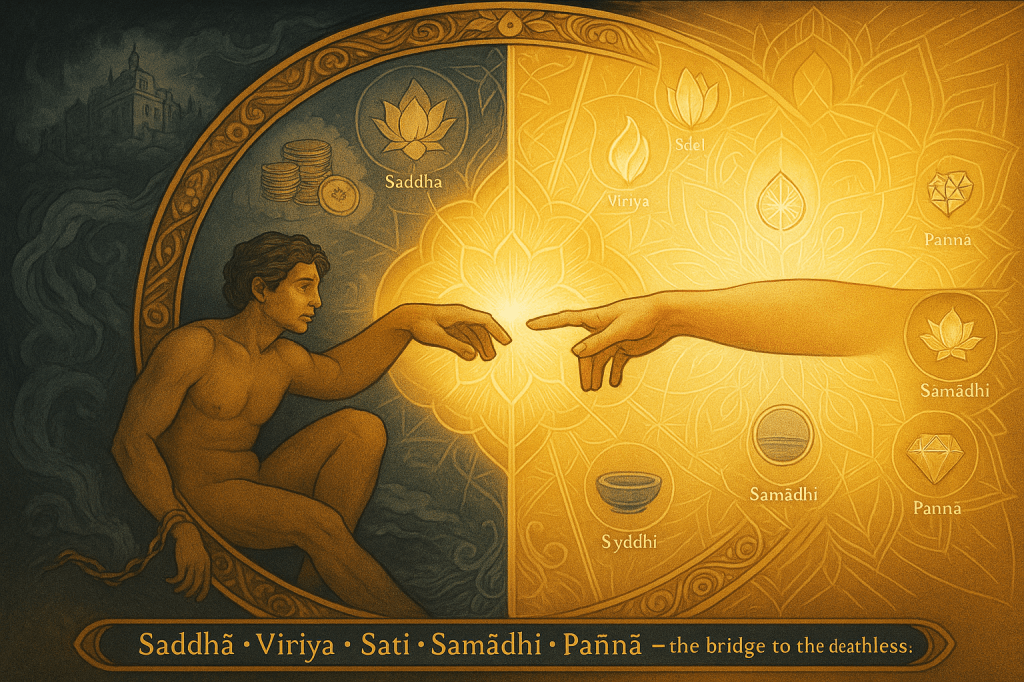

The Buddhist Parallel

From a Buddhist perspective, this fresco mirrors a drama described in the suttas: the real self (citta) yearning for the deathless, while trapped in the worldly self of the aggregates.

- Adam = the citta in bondage – reclining on earth, representing the body and the five aggregates of worldly existence (form, feeling, perception, volition, consciousness aggregate). The hand extended is the luminous citta reaching beyond the aggregates.

- God = Nibbāna – the unconditioned realm, always extending its presence. The Buddha called it amata-dhātu—the deathless realm. Like God’s hand, Nibbāna is near, but unseen by those bound to worldly existence.

- Sophia = Paññā (Wisdom) – just as Sophia represents divine wisdom in Christian iconography, in Buddhism paññā is the faculty by which the citta recognizes illusion and turns toward liberation. Without paññā, the hand cannot reach.

- The Mantle-Brain = Brain Consciousness – in Michelangelo’s fresco, God is enfolded in a shape resembling the brain. For Buddhists, this resonates with the role of brain consciousness: the vast reservoir of this-life memory and human awareness, which must be integrated and transcended.

- The Angels = Pañca Bala (Five Strengths) – the figures around God correspond to the strengths needed for the citta to bridge the gap:

- Saddhā (Faith) = trust in the heart-gateway.

- Viriya (Energy) = the heroic power to reach.

- Sati (Mindfulness) = steady awareness, keeping the hand extended.

- Samādhi (Concentration as lifting power) = the force that propels the citta upward.

- Paññā (Wisdom) = direct vision that the worldly self is illusion.

Thus, what Michelangelo depicted in Christian form finds its Buddhist parallel: the finite citta stretches out from its worldly prison, empowered by strengths, toward the unconditioned presence of liberation.

The Gap Between Worldly Existence and Liberation

Why is there a gap?

In both systems, the answer lies in human limitation.

In Christianity, Adam lacks divine life until touched by God’s Spirit. The gap reveals humanity’s dependence on grace.

In Buddhism, the citta is bound by rāga, dosa, moha. As long as it identifies with the aggregates of worldly existence, its hand falls short.

The Buddha declared:

“Bhikkhus, form aggregate is not self… feeling aggregate is not self… perception aggregate is not self… volitional formations aggregate is not self… consciousness aggregate is not self.” (SN 22.59)

The worldly self fabricated from these aggregates cannot touch Nibbāna. The gap exists because the citta is entangled in illusion.

Bridging the Gap

How is the gap closed?

- In Christianity: through grace, faith, and virtues. God descends, humanity receives.

- In Buddhism: through kāyagatāsati, the five strengths, and the lifting power of samādhi. The citta ascends, Nibbāna receives.

Kāyagatāsati redirects awareness inward: from outward limitation to the heart gateway, into brain consciousness, and beyond into measureless mind. Samādhi provides the lift. The five strengths empower the reach.

The Buddha taught:

“If one thing is developed and cultivated, it leads to the realization of the fruit of knowledge and liberation. What is that one thing? Kāyagatāsati.” (AN 1.570)

This one practice, empowered by the five strengths, is the stretching of the hand across the gap.

Touching the Hand of the Deathless

When the gap is closed, contact is made—not between flesh and flesh, but between the conditioned and the unconditioned.

- In Christianity, Adam’s hand receives God’s touch, and humanity lives by grace.

- In Buddhism, the citta touches Nibbāna and awakens to the deathless.

The Buddha described this moment simply:

“With the fading of craving, liberation. With liberation, knowledge: ‘Released.’” (SN 22.59)

This is the true touching of hands: the finite touching the infinite, the worldly self falling away, the real self standing free.

Two Knowledge Systems, One Truth

Michelangelo’s fresco and the Buddha’s suttas arise from different civilizations, different languages, different metaphysics. Yet both testify to the same existential truth:

- The human condition is a reaching—always yearning for the beyond.

- The infinite is near—always extending itself.

- A gap remains, which cannot be closed by the worldly self alone.

- Strength, wisdom, and grace are required.

In Christian art, it is Adam’s hand and God’s hand, nearly touching.

In Buddhist practice, it is the citta reaching through the heart gateway, empowered by saddhā, viriya, sati, samādhi, paññā, until it touches Nibbāna.

Two systems. Two languages. One truth: that liberation lies just beyond the reach of the worldly, but always within the reach of the real self when it awakens.

8. Vijjā–Vimutti: Knowledge and Liberation

The Fruit of the Path

The Buddha did not stop at exposing illusion. He taught the way to freedom and described its consummation in two words: vijjā-vimutti—knowledge and liberation.

This is the fruit of the Eightfold Path, of kāyagatāsati, of the five strengths. It is the fulfillment of the citta’s journey: to know truly, and to be free.

What Is Vijjā?

The word vijjā in Pāli is often rendered “knowledge.” Yet in the Buddha’s teaching, its meaning is deeper than intellectual understanding.

- Vijjā is inclusive: it embraces scientific knowledge, historical knowledge, and all forms of inquiry that reveal the nature of this world. Such knowledge is valuable because it shows us the laws that govern phenomena—whether at the scale of galaxies or cells.

- But vijjā goes further: it is not only about describing the world, but about penetrating to its deepest nature.

- To see that this world is impermanent (anicca), subject to decay and death.

- To see that mankind’s state of existence is dukkha, unsatisfactory, trapped in a cycle we did not choose.

- To see that this cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra) is involuntary, driven by craving and ignorance.

- And most importantly: vijjā means knowing the way out—the path of liberation.

Thus vijjā is knowledge of the truth of this world, the truth of human existence, and the way to be liberated from both.

The Inseparability of Vijjā and Vimutti

The Buddha never spoke of vijjā in isolation. It is always paired with vimutti—liberation.

Why? Because in the highest sense, to know is to be free.

- If we see impermanence intellectually but still cling, we do not know.

- If we describe saṃsāra as endless rebirths but still crave existence, we do not know.

- True vijjā is liberating by nature. It dissolves illusion and cuts the cords of bondage.

This is why the Buddha described the arahant’s realization:

“With the destruction of the taints, the mind is liberated. When it is liberated, there is knowledge: ‘Released.’” (SN 22.59)

Here, knowledge (vijjā) and liberation (vimutti) arise together, as one taste—the taste of freedom.

From Limited Knowing to Liberating Knowing

Human beings already possess remarkable knowledge. Brain consciousness is a vast reservoir of this-life information: memory, culture, science, philosophy. All of this is valuable—it maps the world.

But vijjā is more than mapping. It is existential knowledge:

- To see that all maps are of a burning house.

- To recognize that mankind is trapped in an involuntary cycle of existence.

- To understand that knowledge which does not show a way out is incomplete.

Thus the Buddha described ignorance (avijjā) as not merely “not knowing facts,” but “not knowing the Four Noble Truths”:

- Not knowing suffering.

- Not knowing the origin of suffering.

- Not knowing cessation.

- Not knowing the path.

Vijjā is therefore knowledge of the Four Noble Truths—especially the last two: cessation (nirodha) and the path (magga).

Knowledge of the Path

Here lies the heart of vijjā: it is path-knowledge (magga-vijjā).

It is not enough to know that this world is impermanent. One must know how to step out of it.

The Buddha emphasized training:

- Sīla (ethical discipline) to purify conduct.

- Samādhi (concentration, the lifting power of the mind) to free awareness from the physical dimension.

- Paññā (wisdom) to see through illusion and abandon clinging.

This is the liberating path. Vijjā is the knowledge that such a path exists, that it works, and that it leads beyond saṃsāra into Nibbāna-dhātu.

This is why your teaching, Bhante, emphasizes not only doctrine but training. True vijjā is not abstract—it is embodied knowledge of how to walk the path.

Liberation: Vimutti

If vijjā is knowing, vimutti is the being-free that follows.

The word vimutti means release, letting go, unbinding. When the citta, seated in the heart, passes through brain consciousness and expands into measureless mind, it eventually sees that even universal consciousness is conditioned. Letting go of all attachment, it awakens to the unconditioned.

This is liberation:

- From the aggregates of worldly existence.

- From the false self of ego.

- From the involuntary cycle of saṃsāra.

- From aging and death.

It is entry into Nibbāna-dhātu—the deathless realm beyond worlds.

Canonical Foundations

The Buddha described vijjā-vimutti as the true fruit of practice:

- AN 1.570 – Kāyagatāsati, if developed, leads to vijjā-vimutti.

- SN 22.59 – With the fading of craving, liberation. With liberation, knowledge: “Released.”

- MN 38 – The Tathāgata is one who is “liberated by true knowledge” (vijjā-vimuttī).

These passages show the two as inseparable: vijjā is not mere theory, and vimutti is not blind escape. Together they are the full awakening.

Parallel with Christian Tradition

Here the dialogue with Christianity deepens.

- In Christian mysticism, the goal is gnosis—knowledge of God—and theosis—union with the divine.

- Knowledge is not intellectual but participatory. To know God is to be transformed into God’s likeness.

In Buddhism, vijjā is not knowledge of God but of the nature of existence, and the path beyond it. Yet the parallel is clear: knowledge and transformation are inseparable.

Just as the Christian mystic speaks of “knowing and being known,” the arahant speaks of “knowing and being free.”

The Citta’s Journey into Vijjā-Vimutti

Let us trace the journey in terms of your teaching, Bhante:

- The heart gateway – where the citta abides as seat and doorway.

- The brain consciousness – the vast reservoir of this-life knowledge, constantly updating the citta.

- The measureless mind – subconscious, collective, planetary, solar, galactic, universal.

- Vijjā – knowledge that all these are still conditioned, and that liberation lies beyond.

- Vimutti – the actual release, when the citta lets go of all worlds and abides in the deathless.

Living in Liberation

The arahant, liberated through vijjā-vimutti, still lives in the body but is not bound by it.

The aggregates continue, but no longer constitute a self. The worldly self has fallen away. The real self abides in freedom.

Such a one lives “in the world, but not of the world.” Compassion flows naturally, for there is no more clinging to “me” and “mine.”

The Final Horizon

Vijjā-vimutti is not annihilation. It is not “nothingness.” It is entry into the unconditioned.

The Buddha described Nibbāna-dhātu as:

- Amata (deathless)

- Asaṅkhata (unconditioned)

- Ananta (infinite)

- Ajajjara (undecaying)

- Suddhi (pure)

- Mutti (liberated)

This is the final horizon: not more refined existence, but freedom from existence itself. Knowledge and liberation merge here, inseparable.

Conclusion

The path begins with the intuition that “something is wrong.” It unfolds through insight into illusion, the practice of kāyagatāsati, the strengthening of the mind, and the lifting power of samādhi.

It culminates in vijjā-vimutti—knowledge and liberation.

- Knowledge of the truth of the world and mankind’s involuntary bondage.

- Knowledge of the path of liberation.

- Liberation itself, the release of the citta from all worlds into the deathless.

This is the final fruit. This is the grace of Nibbāna: always present, always extending its hand, waiting only for the citta to awaken and take hold.

9. Nibbāna-dhātu: The Deathless Realm Beyond All Worlds

The Buddha’s Final Horizon

All of the Buddha’s teachings point toward a single consummation: Nibbāna-dhātu.

The Noble Eightfold Path, the practice of kāyagatāsati, the cultivation of the five strengths, the lifting power of samādhi, and the fruit of vijjā-vimutti—all converge here.

The Buddha described this not as another world within saṃsāra, but as the unconditioned (asaṅkhata), the deathless (amata), the *unborn and unbecome.

“There is, bhikkhus, that base where there is no earth, no water, no fire, no air… there is no coming, no going, no standing, no dying, no reappearing. This is the end of suffering.” (Udāna 8.1)

This realm is not subject to aging and death. It is not constructed of aggregates. It is freedom itself.

Two Nibbāna ways

The Buddha distinguished two ways Nibbāna-dhātu can be realized:

- Sa-upādisesa-nibbāna-dhātu — Nibbāna with residue remaining.

- This is the liberation of an arahant during life.

- The citta is free, but the aggregates continue until physical death.

- Anupādisesa-nibbāna-dhātu — Nibbāna without residue.

- This is final liberation at death.

- The aggregates dissolve completely.

- The citta abides beyond all worlds, unbound, unconditioned.

In both cases, liberation is the same. The distinction lies only in whether the body remains or not.

Beyond Universal Consciousness

In our exploration of the measureless mind, we traced awareness expanding: subconscious → collective → earth → solar → galactic → universal consciousness.

But even universal consciousness is still conditioned. It is vast, but it belongs to saṃsāra.

Nibbāna-dhātu is different:

- It is beyond the consciousness aggregate (viññāṇakkhandha).

- It is unaggregated consciousness, the luminous citta, free from conditioning.

- It is not part of the universe, but beyond the very structure of universes.

Thus the practitioner must go further than cosmic awareness. The lifting power of samādhi carries the citta past even the measureless, until it abides in the deathless.

Nibbāna as Nirodha (Cessation)

The Buddha often spoke of Nibbāna as nirodha—cessation. But here we must be precise.

- Not annihilation.

- Not blank nothingness.

- Not the destruction of the real self (citta).

What ceases is specifically:

- The worldly existence fabricated from aggregates.

- The worldly self (ego)—the false identity tied to form, feeling, perception, volition, and aggregated consciousness.

- The worldly suffering (dukkha) of aging, sickness, and death.

- The involuntary cycle of rebirth into saṃsāra.

Thus:

- Nirodha = cessation of bondage.

- Nibbāna = freedom of the citta.

The citta, freed from aggregation, does not vanish. It abides in Nibbāna-dhātu—the deathless, unconditioned, infinite.

As the Buddha said:

“This is peaceful, this is sublime: the stilling of all formations, the relinquishing of all acquisitions, the destruction of craving, dispassion, cessation, Nibbāna.” (AN 3.32)

The Negative Descriptions

Because Nibbāna is beyond conditioned experience, the Buddha often described it in negative terms:

- Anidassana — non-manifestative.

- Anidassana-viññāṇa — consciousness invisible to the eye, beyond form.

- Ajāta — unborn.

- Abhūta — not-become.

- Akata — not-made.

- Asaṅkhata — unconditioned.

These phrases point by negation. They tell us what Nibbāna is not: not born, not made, not subject to death. This protects us from imagining it as just another world.

The Positive Descriptions

Yet the Buddha also spoke positively of Nibbāna’s qualities:

- Santi — peace.

- Sukha — bliss.

- Mutti — liberation.

- Suddhi — purity.

- Amata — deathless.

- Dhruva — permanent.

These are not metaphors but direct descriptions. The arahant who abides in liberation experiences Nibbāna as the highest happiness (paramaṃ sukhaṃ).

Thus Nibbāna is not annihilation, but the truest life—the state where the citta is beyond all death.

Distinction from the False Self

The Buddha’s teaching must always distinguish between the worldly self and the real self (citta).

- The worldly self (ego) is fabricated from aggregates. It is impermanent, unsatisfactory, and not-self. It ceases at liberation.

- The real self (citta) is luminous, unaggregated, and capable of liberation. It is not destroyed.

Thus Nibbāna is not the death of the real self. It is the liberation of the real self from all worlds.

The Citta in Liberation

When liberated, the citta abides:

- Unaggregated — no longer entangled with form, feeling, perception, volition, or conditioned consciousness.

- Unconditioned — no longer bound to karmic cause and effect.

- Deathless — no longer subject to aging, sickness, or death.

- Infinite — not limited by body, brain, or universe.

This is why Nibbāna is called amata-dhātu—the deathless realm.

Parallel with Christian Mysticism

Here again we can draw parallels with Christian teaching.

- Christian theology speaks of heaven as union with God. Yet heaven, as commonly imagined, is still a world—a place with form, with angelic beings, with divine presence. In Buddhist terms, it would be part of saṃsāra.

- Christian mystics, however, spoke of a deeper reality: theosis—union with the divine essence, beyond all images. Meister Eckhart wrote of “the birth of God in the soul,” which is beyond heaven and earth.

In this, Christian mysticism comes close to the Buddhist view: the final goal is not another world, but the unconditioned.

Yet the difference remains: for Buddhists, Nibbāna is not union with a God, but the liberation of the citta into the unconditioned dhātu.

The Path Converges Here

All elements of the path converge in Nibbāna-dhātu:

- Kāyagatāsati directs awareness inward, opening the heart doorway.

- Pañca Bala (five strengths) empower the journey, steadying the citta.

- Samādhi provides the lifting power of the mind to rise beyond worlds.

- Paññā sees the aggregates as not-self and abandons clinging.

- Vijjā-vimutti arises: knowing the truth and being free.

When these come to fruition, the citta releases all grasping and abides in the deathless.

Living in the World, Not of the World

The arahant, while still alive, demonstrates Nibbāna with residue. They eat, walk, speak, and interact, but no longer identify with body or mind as self.

They live in the world, but not of the world. Their citta already abides in Nibbāna, even while the body continues.

Thus the Buddha described the arahant as:

“Freed by wisdom, the taints destroyed, they live having done what is to be done, their burden laid down, the goal attained.” (MN 140)

The Final Horizon

At death, when the aggregates dissolve, the liberated one abides in Nibbāna without residue.

This is the final horizon:

- No more rebirth.

- No more aging and death.

- No more bondage to saṃsāra.

It is not annihilation. It is fulfillment. The real self, freed from all fabrication, abides in the unconditioned.

Conclusion

Nibbāna-dhātu is the Buddha’s final horizon:

- The cessation of worldly existence, worldly self, worldly suffering.

- The liberation of the real self (citta) into the unconditioned.

- The deathless realm beyond all universes.

The path of training—sīla, samādhi, paññā; kāyagatāsati, pañca bala, vijjā-vimutti—all converge here.

This is the fruit of the journey from “something is wrong” to the Right Awakening: not another world, but the end of all worlds.

This is the grace of Nibbāna, always present, always extending its hand, awaiting only the citta’s release.

10. A Practical Epilogue — Walking the Path to the Deathless

The Modern Intuition: “Something Is Wrong”

For many people today, there is a growing intuition: something is wrong with the way we live. The world appears real, yet strangely hollow. We sense that beneath the glitter of technology and progress, something fundamental is unstable.

Science deepens this awareness. Physics shows that matter is not solid but a play of forces. Biology reveals the inescapable laws of aging and death. Neuroscience uncovers the constructed nature of perception. Philosophy echoes the same: the world is māyā, appearance without ultimate substance.

This is not despair but the beginning of wisdom. It is the same starting point that led Siddhattha Gotama to renounce the palace life. The feeling that “something is wrong” is the seed of awakening. It is the call to seek not just improvement of life, but liberation from the cycle of involuntary existence.

Turning Inward: Kāyagatāsati as the Gateway

When awareness is directed outward—toward objects, possessions, social roles—it is limited. The more we chase, the more fragile we feel. Outward awareness is always bound to change.

But when awareness is directed inward, it becomes measureless. This is the practice of kāyagatāsati—mindfulness directed to the body.

- Begin with the body. Observe breathing, postures, daily activities. See the body’s impermanence.

- Enter the heart. The heart is the seat and gateway of the citta. It is not the storehouse of all consciousness, but it is the doorway to deeper dimensions.

- Link with the brain consciousness. The brain is the reservoir of this-life knowledge, memory, and culture. It constantly updates the citta.

- Expand through the gateway. Awareness moves into the subconscious, collective, planetary, solar, galactic, and universal fields.

Through kāyagatāsati, the citta learns that inward attention is infinite. The body becomes not a prison, but a doorway to the measureless.

Cultivating the Five Strengths (Pañca Bala)

The Buddha taught that five inner strengths sustain the path of liberation. Without them, practice falters. With them, the citta grows unshakable.

- Faith (Saddhā). Trust that liberation is real. Trust the heart as the doorway. Trust the Buddha’s path.

- Energy (Viriya). The steady courage to persist. Effort to overcome laziness and distraction.

- Mindfulness (Sati). Presence that keeps awareness stable across body, brain, and cosmic fields.

- Samādhi. Not mere calm, but the lifting power of the mind—the force that elevates the citta beyond the physical dimension.

- Wisdom (Paññā). The clear seeing that worldly existence is impermanent, unsatisfactory, and not-self—and that Nibbāna is release.

These five are not optional. They are the muscles by which the citta stretches its hand across the gap toward the deathless.

The Practice of Samādhi as Lifting Power

Samādhi is often misunderstood as simple concentration. In truth, it is much more.

- Samādhi is the lifting power of the mind.

- It makes the citta buoyant, weightless, capable of rising beyond the aggregates.

- It transforms awareness from scattered thoughts into a unified beam strong enough to pierce illusion.

The practice begins with samatha—not mere calm, but deliberate cultivation of samādhi. The citta grows stable, luminous, and strong.

Then the lifting begins:

- From breath to body.

- From body to subtle energy.

- From energy to expanded awareness.

- From awareness to the measureless mind—subconscious, collective, planetary, cosmic.

Samādhi carries the citta upward, beyond form and time, until it approaches the unconditioned.

Wisdom as Path-Knowledge (Magga-Vijjā)

Wisdom (paññā) is not only seeing the aggregates as impermanent. It is knowing the path of release.

This is magga-vijjā—path-knowledge.

- To see the nature of the world: impermanent, bound to aging and death.

- To see the nature of mankind’s state: trapped in involuntary rebirth.

- To know the way out: the Eightfold Path, the practice of mindfulness, the cultivation of strengths, the lifting of samādhi.

Vijjā is not abstract theory. It is practical, liberating knowledge. It is the map and the skill of walking the path. Without path-knowledge, vision alone leads to despair. With path-knowledge, vision leads to freedom.

Living Training in the World Today

The path is ancient, yet it must be lived in modern life.

- Ethics (Sīla). Live with simplicity, harmlessness, and truth. Keep precepts not as rules but as protection for the citta.

- Meditation (Bhāvanā). Daily practice of kāyagatāsati. Return awareness inward. Build samādhi steadily.

- Reflection. Contemplate impermanence, aging, sickness, and death—not to sadden the mind, but to free it from illusion.

- Community. Walk with others on the path. Support and be supported.

The practitioner does not need to escape outwardly, but inwardly must disengage. Live in the world, but not of it.

The Fruit: Vijjā-Vimutti

As training matures, the citta loosens from the aggregates. It sees the body, feelings, perceptions, volitions, and consciousness as worldly processes—not self.

At this stage, vijjā arises: the deep knowing of the truth of the world, of mankind’s state, and of the path of liberation.

With knowledge comes release. Vimutti follows naturally. The worldly self falls away. The real self abides in freedom.

The arahant described this with simplicity:

“Birth is destroyed, the holy life fulfilled, what had to be done is done. There is no more of this to come.” (MN 72)