This article arises from a sincere question:

“Bhante, why don’t you teach kamma? Everyone says it is the essence of Buddhism.”

It’s true—many Buddhist teachers talk a lot about kamma (karma). They explain how good deeds lead to good rebirths, how bad deeds lead to suffering. People are encouraged to fear evil and do good, so that when wholesome kamma ripens, they will enjoy a better life in the future.

But my way of teaching is different. Not because I deny kamma, but because I refuse to make it the center of Dhamma.

Kamma is like gravity—it governs the world. But the Buddha’s gift was to show the path beyond gravity, into the deathless.

Kamma Is Universal

Kamma simply means intentional action. The law of kamma is universal: actions bring consequences. Just like gravity makes the apple fall, kamma shapes our lives.

But remember: this law was known long before the Buddha. Brahmins, Jains, and many other Indian teachers already spoke about karma.

The Buddha did not renounce the palace and spend six years in austerity simply to re-teach a universal law. He discovered something far greater: the path that leads beyond kamma altogether—into the deathless.

The Traditional Way—and Its Limits

Traditional Buddhism often presents kamma like a cosmic reward-and-punishment system:

- Do good, get heaven.

- Do bad, fall into hell.

- Today’s joy and sorrow? The fruit of past karma.

Yes, this keeps people moral. But it also keeps them inside saṃsāra. It is like teaching people how to fall softly under gravity, instead of showing them how to fly beyond gravity.

The Buddha’s message was not: “make better karma for your next life.” It was: “end karma, end becoming, enter the deathless.”

My Way of Teaching Kamma

I affirm the law of kamma. But I teach it differently.

I teach that the highest kamma is not charity for better rebirth, but actions that weaken defilements and free the mind.

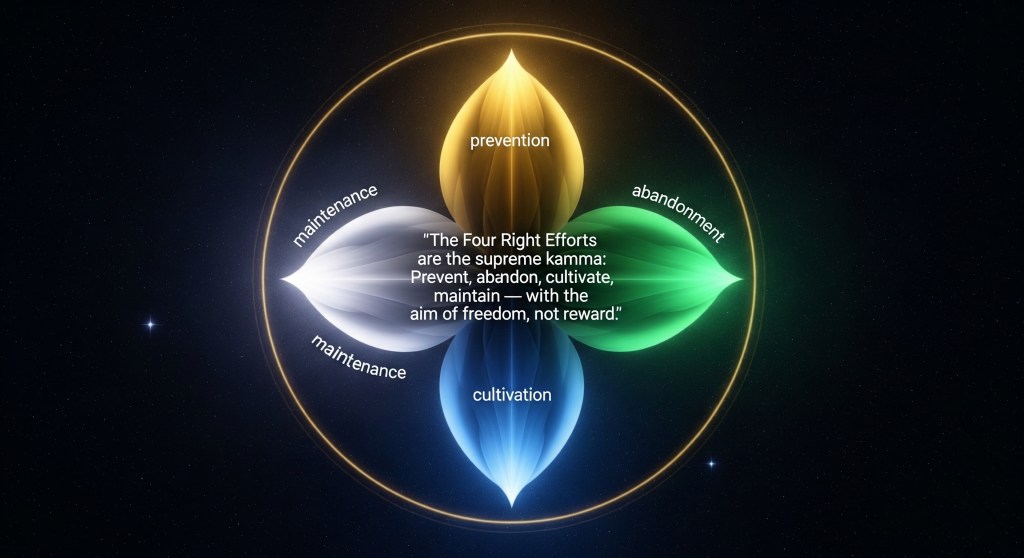

The Buddha’s Four Right Efforts are the supreme kamma practice:

- Prevent unwholesome states.

- Abandon unwholesome states.

- Cultivate wholesome states.

- Maintain wholesome states.

These are not about banking merit for the future. They are about cleansing the heart now—eliminating rāga (attachment), dosa (hatred), and moha (ignorance).

I don’t teach kamma as fear and reward. I teach it as background law—and then point beyond it, toward liberation.

Worldly Good vs. Liberative Good

There are two kinds of wholesome action:

- Worldly wholesome kamma – generosity, kindness, morality. These bring harmony, happiness, and good rebirths. Good, but still within saṃsāra.

- Liberative wholesome kamma – mindfulness, wisdom, insight. These uproot craving and ignorance. They lead beyond saṃsāra.

The Buddha did not come merely to improve saṃsāra. He came to show the way out.

Worldly good kamma brings happiness. Liberative good kamma uproots craving. Only the latter leads to Nibbāna.

Living with Kamma Without Being Bound by It

Yes, kamma governs life—like gravity. But we don’t live as karmic accountants, tallying merits and demerits.

We live ethically, not for future reward, but because ethics clears the mind.

We meditate, not for merit, but for freedom.

We let go, not for rebirth in heaven, but to step outside the karmic machine.

Why I Didn’t Teach the Kamma (in the usual way)

So why didn’t I teach kamma?

Because I don’t teach it as fear-based morality, or as a cosmic ledger of reward and punishment.

I teach it as background law. And then I point beyond it—toward liberation.

Yes, actions matter. But the goal is not a better life in this world, nor a better rebirth in the next. The goal is freedom from rebirth altogether.

Kamma is true, but it is not ultimate.

The Buddha’s unique gift was to show the way beyond kamma, to Nibbāna-dhātu—the deathless realm, free from aging and death.

That is why I didn’t teach kamma the way others do. I teach the path of liberation.

1. Introduction: Carol’s Question

This article arises from a question raised by Carol, and I welcome such sincere and inquisitive questions. She asked me: “Bhante, why don’t you teach kamma? So many Buddhist teachers and monks talk about it, but you rarely emphasize it. Why is that?”

It is true. In many Buddhist traditions, the teaching of kamma (or karma in Sanskrit) is central. Teachers emphasize that if you do good, you will receive good results; if you do bad, you will receive bad results. People are encouraged to avoid unwholesome actions for fear of suffering in the future, and to cultivate wholesome actions for the promise of rewards in future lives.

In this way, kamma is often used as the main motivation for morality. Some teachers even go to great lengths to explain in detail how karma works, how rebirths unfold, and how cause and effect ripple through countless lifetimes.

But my approach is different. It is not that I deny the law of kamma. I acknowledge it fully. Yet I do not teach kamma in the same way that many traditional teachers do. Why? Because my focus is not a fear-based practice, but a hope-based one.

Kamma is not unique to Buddhism. It is a universal law of cause and effect. My role as a teacher is not to repeat what everyone already knows—that actions have consequences. My role is to teach what is unique to Gautama Buddha’s realization: the path that leads beyond kamma, beyond rebirth, beyond saṃsāra, into the deathless Nibbāna-dhātu.

So in this article, I will indeed teach kamma. But my teaching is different: I encourage actions that lead not to a “better worldly life,” but to liberation itself.

2. Kamma as a Universal Law

Kamma simply means “action.” In Buddhist context, it especially means intentional action of body, speech, and mind. And the law of kamma means that such actions bring consequences—sometimes immediately, sometimes later, sometimes even in future lives.

This law is as natural as gravity. Just as the law of gravity governs how an apple falls to the ground, the law of kamma governs how actions shape lives. You don’t need to “believe” in gravity for it to work; the same is true for kamma.

Long before the Buddha, Indian traditions—Brahmanism, Jainism, and many other śramaṇa schools—already taught karma. The idea that actions bring consequences was already common knowledge in spiritual circles.

This is why I say: kamma is not the unique teaching of Gautama Buddha. He did not leave the palace, renounce his royal life, and practice austerities for six years simply to re-teach a moral law that was already well known. He sought something higher, something no one else had found: a path not only to understand kamma, but to go beyond its reach.

Kamma is true. But Nibbāna is beyond kamma.

3. The Traditional View of Kamma and Its Limitations

In “traditional Buddhism,” especially in popular religious contexts, kamma is taught in a transactional way:

- Do good deeds, and you will be reborn in heaven.

- Do evil deeds, and you will fall into hell.

- Your present life’s joys and sorrows are the ripening of past karma.

This teaching is not entirely false. It is true that actions lead to consequences, and rebirth is one way these consequences manifest. Such teachings restrain people from evil and encourage generosity. They help societies maintain morality.

But the limitation is clear: this teaching still keeps people bound within saṃsāra. It teaches people how to move around within the cycle of birth and death, but not how to get out of it.

It is like teaching people how to fall more gently under gravity—when the real question is: can we learn to fly beyond gravity itself?

The Buddha’s genius was not in explaining the details of kamma’s working. His genius was in pointing to liberation beyond kamma.

4. The Buddha’s Radical Teaching: Liberation Beyond Kamma

The Buddha did not aim for a “better rebirth.” He aimed for the end of rebirth.

He saw aging, sickness, and death as universal laws of existence. He realized that as long as we remain within the cycle of conditioned becoming, we are bound by kamma. Good kamma may lead to heaven, bad kamma may lead to hell, but both are still within saṃsāra.

His discovery was Nibbāna-dhātu—the deathless, the unconditioned. This realm is beyond cause and effect. It is beyond the reach of kamma.

This is the most radical part of the Buddha’s teaching. Every other teacher in his time spoke of karma, merit, and better rebirths. The Buddha alone said: You can end the whole process. You can be free of karma itself.

This is why I do not teach kamma in the same way as others. I teach it only as background, as a universal law like gravity. But my true focus is on what the Buddha uniquely discovered: liberation beyond kamma.

5. From Fear-Based to Hope-Based Practice

Most kamma teachings are fear-based. They warn: “If you do evil, you will suffer in hell.” They encourage: “If you do good, you will enjoy heaven.”

But the Buddha’s message was not fear, and not even hope for heavenly pleasure. His message was hope for liberation: freedom from aging and death, from saṃsāra itself.

When people are taught kamma only as reward and punishment, their practice becomes transactional: “If I do this, I will get that.” Their motivation is external: fear of punishment or desire for reward.

I do not teach that way. I emphasize hope-based practice: the hope of freedom, the possibility of liberation.

Wholesome actions are good, not because they guarantee a pleasant rebirth, but because they weaken defilements here and now. They purify the mind. They prepare the citta for release.

The Four Right Efforts are the supreme kamma: prevent, abandon, cultivate, and maintain—with the aim of freedom, not reward.

6. The Four Right Efforts as Supreme Kamma

The Buddha gave us the Four Right Efforts (sammā-vāyāma):

- Prevent unwholesome states from arising.

- Abandon unwholesome states that have arisen.

- Cultivate wholesome states that have not yet arisen.

- Maintain and perfect wholesome states that have arisen.

Many teachers present these as ways to generate “good kamma” for the future. But the deeper truth is: they are methods to uproot defilements in the present.

When we practice the Four Right Efforts, the focus is not on “earning good karma for the next life,” but on purifying the mind here and now. The result is freedom from rāga (attachment), dosa (hatred), and moha (ignorance)—the very forces that bind us to the cycle of kamma and rebirth.

This is why I teach the Four Right Efforts as the highest form of kamma practice: kamma directed toward ending kamma.

7. Wholesome Action vs. Liberative Action

It is important to distinguish between two kinds of wholesome action:

- Wholesome worldly kamma – generosity, kindness, morality, compassion. These bring happiness, social harmony, and good rebirths. They are good and should not be abandoned.

- Wholesome liberative kamma – mindfulness, right view, meditation, insight. These do more than bring good rebirth; they uproot craving and ignorance. They lead toward Nibbāna.

The first type keeps us moving in circles within saṃsāra. The second type directs us toward the exit.

My focus is on the second type. Not because the first is useless, but because the Buddha did not come just to make life within saṃsāra a little better. He came to show the way out.

8. Living in the World Without Being Bound by Kamma

So how should we relate to kamma?

We should acknowledge it, just as we acknowledge gravity. It governs life in the world. But we do not need to obsess over it. We do not need to live like karmic accountants, tallying good deeds and bad deeds, hoping the balance will favor us.

Instead, we live with wisdom. We cultivate wholesome conduct, not for the sake of future rewards, but to support freedom now.

We live ethically because it clears the mind. We meditate because it purifies defilements. We let go because only letting go leads to release.

This way, we live in the world, but we are not bound by kamma.

The Buddha did not come to make saṃsāra a little better. He came to show the way out of saṃsāra altogether.

9. Conclusion: Why I Didn’t Teach the Kamma (in the Usual Way)

So why didn’t I teach kamma?

Because I do not teach it the way others do—as the central theme, as a fear-based motivator, as a transactional system of rewards and punishments.

Instead, I teach kamma as a universal law, acknowledged but not obsessed over. I teach that its highest use is to guide us toward liberation.

Yes, wholesome actions matter. Yes, morality matters. But the goal is not a better rebirth. The goal is freedom from rebirth altogether.

Kamma is true, but it is not ultimate. The Buddha’s unique gift was not to explain karma, but to point beyond it. He showed the way to Nibbāna-dhātu—the deathless, unconditioned realm, beyond kamma, beyond saṃsāra, beyond aging and death.

This is why I didn’t teach kamma in the usual way. I teach the path to liberation.

Leave a comment