by Bhante Mudita Thera

Introduction: Rethinking the Old Story

For generations, textbooks and popular works have portrayed the Buddha as a rebel against Brahmanism. We are told that he rejected the Vedic worldview, denied the ātman, and opposed the Brahmanas who monopolized spiritual authority. In this narrative, Buddhism appears as an “anti-Brahmanical” movement, a radical departure from India’s religious mainstream.

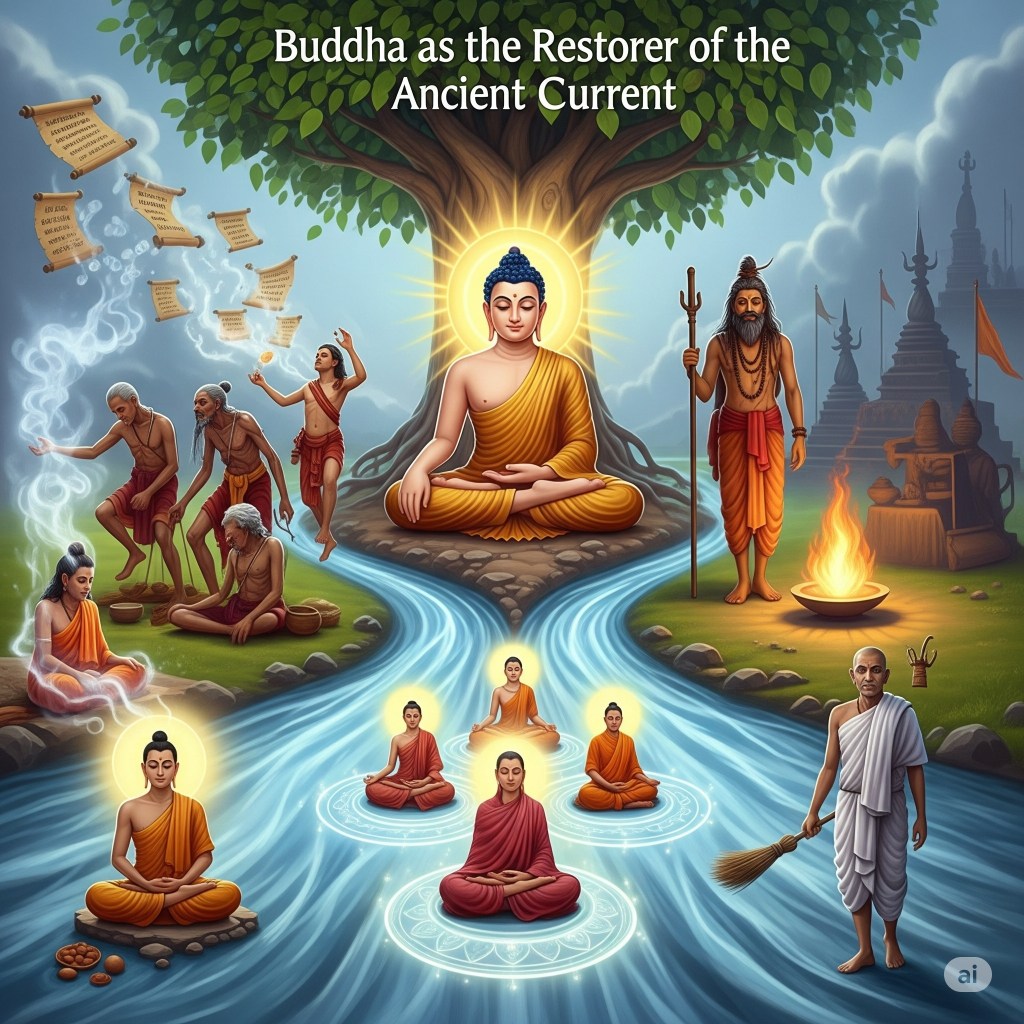

But what if this story is incomplete — or even distorted by centuries of polemics, later sectarian disputes, and the lens of colonial scholarship? What if, instead of conflict, we discover continuity — not continuity in the sense of blind inheritance, but as a restoration of something ancient and profound that had been corrupted by ritualism and social privilege?

This essay explores that possibility. By revisiting early sources and the broader context of India’s Śramaṇa and Brahmanical traditions, we can see the Buddha not as an outsider but as a restorer of true Brahmana conduct, a seeker who inherited the yogic power of the Śramaṇas, purified their practices, and wove them together with the ancient wisdom of the seers (ṛṣis). Alongside this, we can compare how Jainism and other Śramaṇa movements related to the same spiritual current.

The result is a picture of Buddhism’s origins not as conflict, but as continuity transformed — a continuity with the deepest layers of India’s spiritual quest, reshaped into a path of liberation.

The Landscape of Ancient India: Vedic-Brahmanic and Śramaṇa Currents

Brahmanism: From Ritual to Wisdom

The early Vedic tradition was originally the domain of seers (ṛṣis) who sought truth beyond the material. Yet by the Buddha’s time, Brahmanism had largely decayed into ritual sacrifice, priestly privilege, and caste exclusivity. The Upaniṣads preserved glimpses of the older vision: a wisdom-centered search for the ātman, the indestructible refuge beyond death. But these currents were often overshadowed by the dominance of sacrificial religion.

The Śramaṇa Movements: Yogis and Wanderers

Parallel to the Brahmanical order, the Śramaṇa traditions embodied India’s ancient ascetic quest. They practiced jhāna (meditative absorption), samādhi (concentration), tapas (austerities), and iddhi (psychic powers). Their goal was transcendence of the human condition, often through severe renunciation or mystical disciplines. But alongside these profound practices, Śramaṇas also cultivated spells, incantations, and ritual magic — elements the Buddha would later reject.

A Shared Spiritual Current

Despite differences, both Brahmanical and Śramaṇa traditions flowed from the same primordial shamanic current: the human quest to break free from mortality, to find the deathless. By the 6th–5th century BCE, these currents intermingled and competed across the Ganges plain, creating the rich religious landscape into which Siddhattha Gotama was born.

The Buddha: Seeker of a Middle Way

Inheriting Śramaṇa Discipline

The Buddha’s own renunciation followed the Śramaṇa model. He studied under masters like Āḷāra Kālāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta, mastering profound meditative states. He experimented with extreme austerities for six years, pushing his body near death. From the Śramaṇas, he inherited meditation, samādhi, and yogic power — but he came to see that austerity alone could not lead to ultimate freedom.

Restoring Brahmanic Wisdom

In rejecting extreme asceticism, the Buddha was not rejecting wisdom. On the contrary, his awakening rediscovered the ancient Brahmanic vision of paññā — insight into the eternal refuge beyond the body. In the suttas, he repeatedly identifies the true Brahmana not by birth but by conduct, linking himself to this lineage of seers. When he declares, “I am a Brahmana, one who has laid down the burden,” he restores the dignity of the word, lifting it out of caste privilege back into spiritual truth.

Innovating Vinaya

What the Buddha added — uniquely his own — was the Vinaya, a monastic discipline not found in either Brahmanism or Śramaṇa traditions. Vinaya served a double purpose:

- Safeguard: protecting the Saṅgha from corruption and social entanglement.

- Renunciation-engine: pulling the mind away from worldly attachments, creating the psychological and social space where samādhi and paññā could thrive.

This triple foundation — Śramaṇa samādhi, Brahmanic paññā, and the Buddha’s Vinaya — became the architecture of Early Buddhism.

The Buddha and Brahmanism: Conflict or Restoration?

Rejecting Ritual Sacrifice, Not Wisdom

The Buddha’s discourses often critique Brahmanical ritualism, animal sacrifice, and caste exclusivity. But nowhere does he deny the existence of the ātman in the simplistic sense attributed by modern interpretations. What he rejects is attachment to identity — whether body, feeling, or concept — as “self.” He dismantles all false identifications so that the mind can open to the deathless element (amata dhātu).

In this way, his teaching can be seen not as a negation of the Upaniṣadic quest, but as its fulfillment through practice. Where the Brahmanical seers intuited the eternal refuge, the Buddha laid down a practical path to realize it.

Buddha as True Brahmana

The Pāli Canon repeatedly records the Buddha calling himself a Brahmana — not in caste terms, but in spiritual terms: one who has cut off craving, destroyed the taints, and lives by Dhamma. Far from being “anti-Brahmanical,” the Buddha restored the dignity of Brahmanahood.

Jainism: A Śramaṇa Sibling

The Jain tradition, contemporary with the Buddha, shared much with Śramaṇa culture: wandering renunciants, extreme austerities, and the quest for liberation. Jainism, however, leaned heavily toward tapas (asceticism) as the decisive path, even to the point of starvation rituals.

The Buddha respected the Jains as fellow seekers but critiqued their reliance on physical mortification. His Middle Way balanced Śramaṇa discipline with wisdom, rejecting extremes of indulgence and torment. In this sense, Jainism represents a parallel branch of the Śramaṇa tree, while Buddhism integrated Brahmanic paññā and Vinaya to create a more balanced path.

The Śramaṇa Umbrella: Purified and Transformed

By the Buddha’s time, the Śramaṇa umbrella included yogis, ascetics, skeptics, materialists, and more. Some were noble seekers; others were magicians, spell-casters, or skeptics denying moral law. The Buddha drew selectively:

- Adopted: meditation, samādhi, jhāna, psychic powers.

- Rejected: incantations, ritual spells, nihilistic skepticism.

- Transformed: austerity → Middle Way; renunciation → guided by Vinaya.

Thus, Buddhism is best seen not as “one Śramaṇa school among many,” but as the purification and transformation of the Śramaṇa stream, married to restored Brahmanic wisdom and grounded in a new institutional framework.

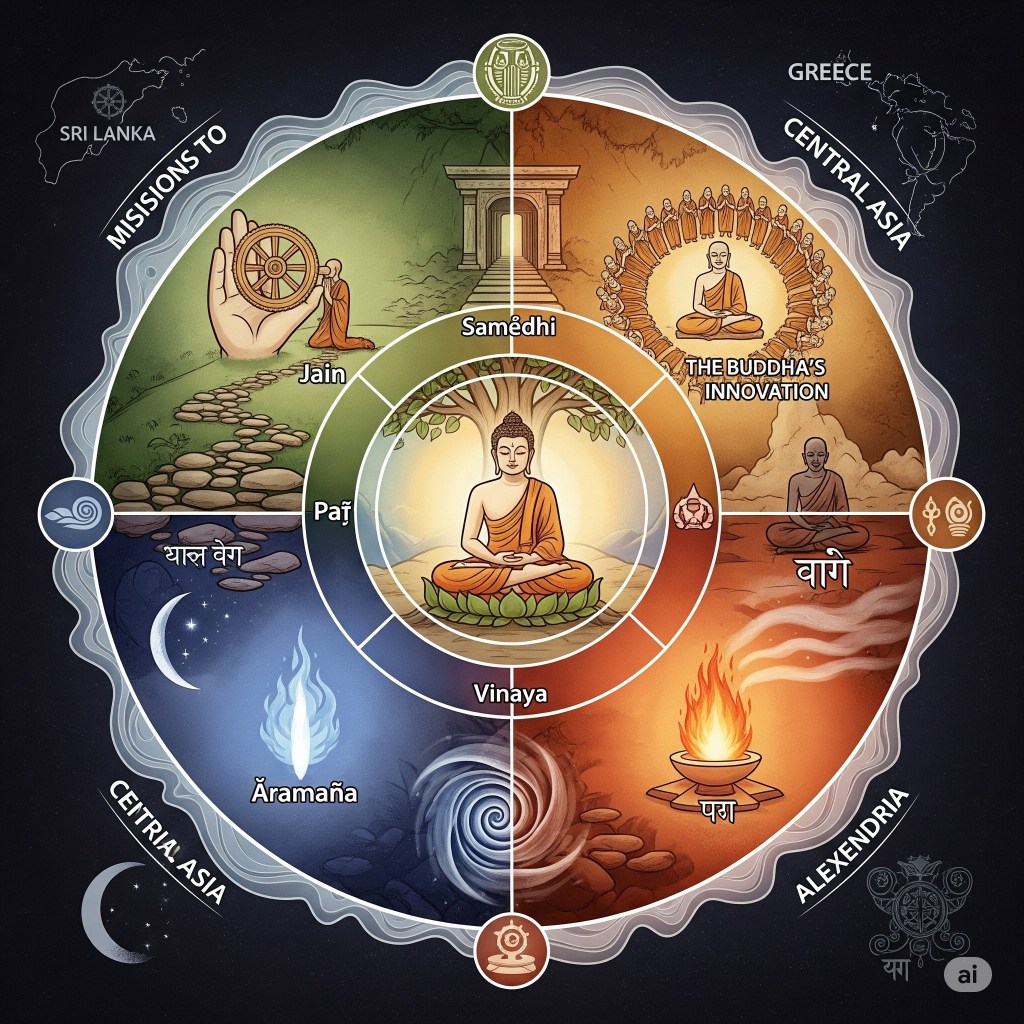

The Triple Foundation: Samādhi, Paññā, and Vinaya

When viewed in its full context, the Buddha’s teaching rests on a threefold foundation:

- Śramaṇa inheritance — the yogic discipline of samādhi.

- Brahmanic restoration — paññā, the wisdom of seeing the deathless.

- Buddha’s innovation — Vinaya, the unique safeguard and renunciation-framework.

Each council of Early Buddhism — First, Second, and Third — focused not only on preserving Dhamma but especially on protecting Vinaya, the Buddha’s own invention, because it was the indispensable condition for sustaining the other two.

Conclusion: Continuity Transformed

The old story of Buddhism as a revolt against Brahmanism no longer suffices. Early Buddhism is not merely “anti-ritualist” Śramaṇism, nor a wholesale rejection of Brahmanism. It is:

- A selective inheritance of Śramaṇa yogic methods.

- A restoration of ancient Brahmanic wisdom, purified of ritualism and caste.

- A unique innovation in the Vinaya system, safeguarding renunciation and ensuring continuity.

In this light, the Buddha was not an outsider but the culmination of India’s primordial spiritual quest — the one who took the fragmented currents of his time and wove them into a liberating path.

For Buddhism, Brahmanism, Jainism, and Śramaṇa traditions, the question is not conflict or continuity, but how continuity is purified, restored, and transformed into a path leading beyond the world, to the deathless Nibbāna.

Mandala of Continuity Transformed: The Buddha at the center, uniting Śramaṇa practice, Brahmanic wisdom, and Vinaya into a path of liberation.

This mandala symbolizes the Buddha’s role not as a breaker of traditions, but as a restorer and transformer of India’s ancient spiritual current. The lower quadrants represent the streams he inherited: Śramaṇa practices of samādhi and jhāna (purified of spells) and Brahmanic wisdom of paññā (freed from ritualism). The side quadrant of Jainism shows a sibling path of tapas and austerity, parallel but distinct. The upper quadrant highlights the Buddha’s unique innovation of Vinaya, encircling and safeguarding the Saṅgha as a renunciant community. At the center, the luminous lotus represents the triple foundation — samādhi, paññā, Vinaya — radiating outward into the world through Aśoka’s missions, showing Early Buddhism as continuity transformed into a universal path.

Leave a comment