by Bhante Mudita Thera

💡🧘 Did you know “therapy” comes from the Therapeutae?

The Greek word therapeutae meant “healers” of the divine.” Philo of Alexandria described them as men and women living by Lake Mareotis in Egypt, practicing renunciation, meditation, fasting, and silence — healing not the body, but the soul.

Their way of life mirrors Buddhist monasticism so closely that many believe they were influenced by missions sent west by Emperor Aśoka. If true, then every time we say therapy or therapist, we’re echoing the Buddha’s legacy as the Great Physician of the mind.

🏛️📜 Did Buddhism Shape Christian Monasticism?

In 1st-century Alexandria, a mysterious group called the Therapeutae lived by Lake Mareotis. They practiced renunciation, silence, meditation, fasting — and welcomed both men and women into their community.

Sound familiar? Their life resembled the discipline of Buddhist monks and nuns far more than any Jewish or Greek practice of the time.

Could they have been influenced by Theravāda Buddhist missions sent westward by Emperor Aśoka after the Third Council? If so, then Christian monasticism — the Desert Fathers, cenobitic life, even the Rule of Benedict — may owe part of its origin to Buddhism. 🌿✝️🛕

👉 👉 Discover the hidden story and Explore above forgotten link here:

Introduction: A Forgotten Bridge

Christianity and Buddhism are often seen as distant cousins in the family of world religions, arising in separate cultural worlds with little direct contact. Christianity, shaped by the Jewish tradition, blossomed in the Mediterranean under Roman rule. Buddhism, born in the Ganges plain under the Bodhi tree, spread across Asia through the discipline of monastic communities.

Yet hidden in the pages of history lies a fascinating overlap: a mysterious contemplative order known as the Therapeutae, described by the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria in the 1st century CE. Living near Lake Mareotis outside Alexandria, these men and women practiced renunciation, celibacy, fasting, meditation, silence, and communal worship.

Their life bore striking resemblances to the Buddhist Vinaya order — more than to any known Jewish sect of the time. Were they influenced by Buddhist missions sent westward by Emperor Aśoka in the 3rd century BCE? Could they represent the missing link between Buddhism and the rise of Christian monasticism?

The mystery deepens when we realize that our English words therapy and therapist descend directly from Therapeutae. If the Therapeutae were indeed shaped by Buddhism, then every time we speak of therapy, we unconsciously echo the Buddha’s role as the healer of the human condition.

This essay explores that hidden history.

Aśoka’s Missions and the Mediterranean World

After the Third Council at Pāṭaliputta (3rd century BCE), Emperor Aśoka dispatched Buddhist missions in all directions. The Pāli chronicles (Mahāvaṃsa) list missions to Sri Lanka, Central Asia, and even to the Greek-speaking world (Yona).

We also have Aśoka’s Greek-Aramaic edicts in Afghanistan, directly addressing Hellenistic subjects. This shows Buddhism was already reaching Greek audiences. With active trade between India and Egypt through the Red Sea and Alexandria, it is entirely plausible that Theravāda monks arrived in Egypt during the Ptolemaic or early Roman era.

Alexandria, the cultural capital of the Mediterranean, became a natural meeting place of East and West.

Philo’s Therapeutae: Healers of the Soul

In De Vita Contemplativa, Philo describes the Therapeutae in remarkable detail:

- They lived outside Alexandria, near Lake Mareotis.

- Both men and women joined their communities.

- They lived simply in small huts, practicing celibacy, fasting, and silence.

- They studied sacred texts allegorically, seeking inner truth.

- They lived alone but gathered weekly for chanting, prayer, and shared meals.

Philo emphasizes their name: Therapeutae, meaning “healers.” But their healing was not of the body; it was of the soul. They practiced what he calls a life of theōria (contemplation), aiming at freedom from passions and union with the divine.

This description could almost be lifted from a Buddhist account of monastic life. The Therapeutae resemble bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs, living under Vinaya, devoting themselves to meditation, chanting, study, and community gatherings.

From Therapeutae to Therapy

The Greek word therapeuō originally meant “to heal.” The Therapeutae were thus “healers of the soul.”

From this root we derive our modern words:

- Therapy

- Therapist

- Therapeutic

In modern English, therapy means treatment of physical or psychological illness. But in its origins, it meant healing through spiritual discipline and renunciation.

If the Therapeutae were shaped by Buddhist monasticism, then our very word therapy carries a hidden Buddhist echo — a linguistic fossil of the time when Buddhist contemplatives influenced the Mediterranean world.

The Buddha as the Great Physician

This linguistic connection aligns with how the Buddha is described in the Pāli Canon. He repeatedly refers to himself as a healer:

- Diagnosis: The First Noble Truth — suffering (dukkha) exists.

- Cause: The Second Noble Truth — craving (taṇhā) is the cause.

- Prognosis: The Third Noble Truth — cessation (nirodha) is possible.

- Prescription: The Fourth Noble Truth — the Noble Eightfold Path is the cure.

This structure mirrors medical science: illness, cause, prognosis, and treatment. The Buddha is the supreme doctor of the mind, offering not just relief from symptoms but complete liberation from the disease of existence.

In the Milindapañha, the monk Nāgasena compares the Buddha to a physician, the Dhamma to medicine, and the Saṅgha to nurses. This image of Buddhism as a healing system was not metaphorical — it was lived.

Original Buddhism as Psychotherapy

Your essay Original Buddhism Is Entirely A Psychotherapy captures this truth directly. The Buddha was not a theologian spinning abstractions, but a psychotherapist of the mind. His concern was not speculation but healing the roots of suffering — greed, hatred, and delusion.

The practices of mindfulness (sati), concentration (samādhi), and insight (vipassanā) are therapies of the psyche, cutting through distorted perceptions and habitual reactions.

The Therapeutae, too, practiced a life of contemplation, fasting, and meditation — disciplines aimed not at pleasing a deity but at healing the passions of the mind.

Seen this way, the Therapeutae were not simply “Jewish monks” but Buddhist-influenced psychotherapists of the soul. Their very name survives in our modern word therapy, confirming the Buddha’s healing legacy.

The Transmission to Christian Monasticism

Egypt later became the cradle of Christian monasticism. The Desert Fathers of the 3rd–4th centuries CE lived in caves, fasted, practiced silence, and cultivated prayer and meditation. Their communal rules echo Buddhist Vinaya:

- Renunciation of property.

- Celibacy.

- Obedience and humility.

- Regular chanting and prayer.

It is highly plausible that the Desert Fathers inherited not only from Jewish Essenes but also from the Therapeutae — and through them, from Buddhism.

Thus, the Christian concept of monastic life as a therapy of the soul may owe part of its origin to Buddhist missions.

A Shared Heritage of Healing

The link between Therapeutae and therapy is not accidental. It encodes a truth: that religion at its best is healing. The Buddha healed the human condition through insight and meditation. The Therapeutae healed through contemplative service. Christian monks healed through prayer and discipline.

Our modern psychotherapists, though secular, carry in their professional title a hidden debt to these ancient healers. Every session of therapy is, in a sense, a continuation of the Buddha’s work — tending to the wounds of the mind, guiding souls toward freedom from suffering.

Conclusion: Therapy as the Legacy of the Buddha

The mystery of the Therapeutae reveals a profound continuity. Through them, Buddhist renunciant ideals may have shaped Christian monasticism. Through language, their name survived into the words therapy and therapist. Through the Buddha’s example, healing became the core metaphor of liberation.

Seen in this light, Buddhism is not only a philosophy or a religion — it is the world’s oldest psychotherapy, a medicine for the human condition. The Therapeutae remind us that this healing current once flowed westward into Egypt, shaping Christianity, and still flows today in our very words.

Every time we speak of therapy, we unconsciously echo the voice of the Buddha — the Great Physician — whose mission was nothing less than the healing of all beings from the sickness of suffering.

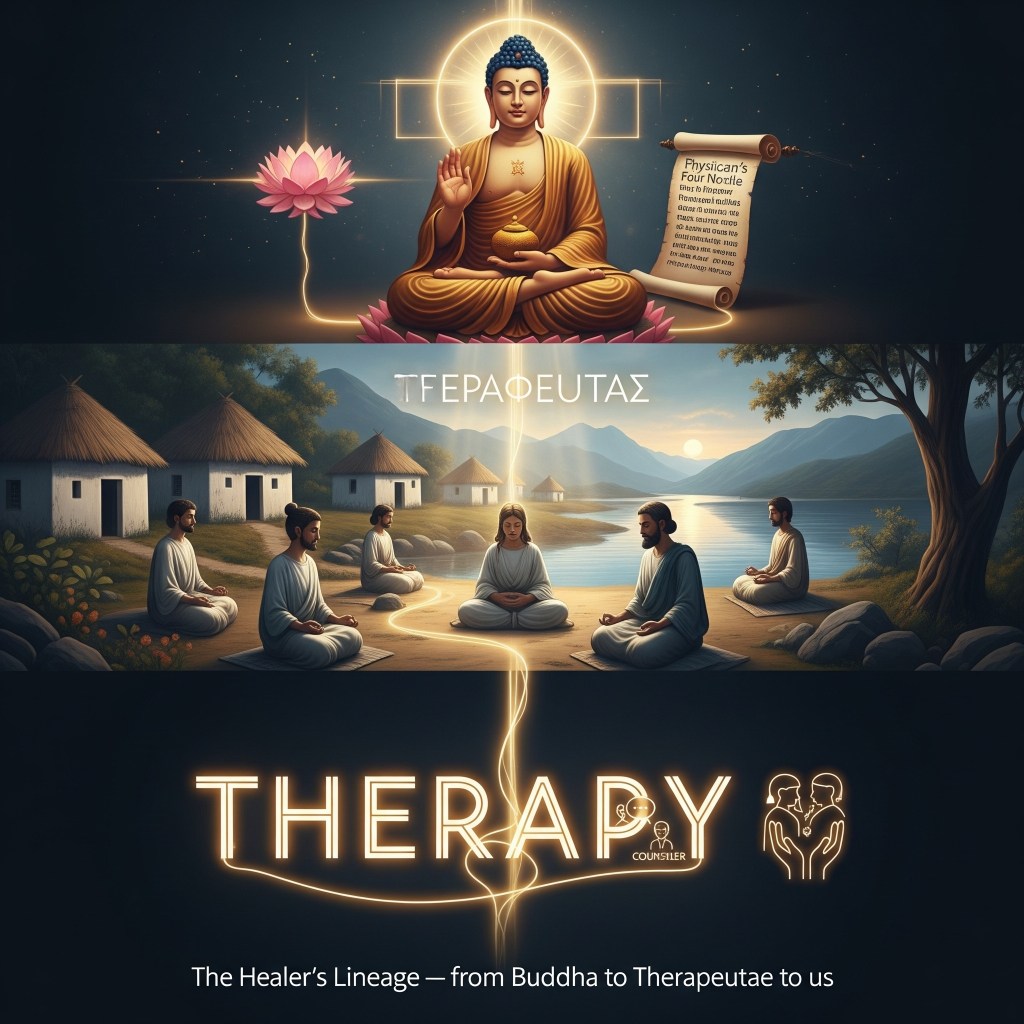

The Healing Lineage: from the Buddha as Great Physician, through the Therapeutae of Alexandria, to our modern word “therapy.”

This image portrays the continuity of healing as the essence of the Buddhist path. At the top, the Buddha appears as the Great Physician, diagnosing the human condition through the Four Noble Truths and prescribing the Noble Eightfold Path as cure. His healing current flows into the Therapeutae of Alexandria, contemplatives who lived by meditation, fasting, and silence — physicians of the soul whose very name survives in our words therapy and therapist. At the bottom, the English word THERAPY glows with the same golden thread, reminding us that modern healing practices, even in psychology and medicine, carry a hidden legacy from the Buddha’s mission. In this sense, Original Buddhism is indeed a psychotherapy — the world’s oldest healing science of the mind.

Leave a comment